THE NATION : MEDICINE : ‘Runaway’ Health-Care Spending? It’s the Engine of New U.S. Economy

- Share via

NEW YORK — One of the safest political bets is that when ideologues of both parties agree on something, they’re probably wrong. Remember the Soviet “missile gap,” of the 1950s? Or the Japanese takeover of America in the 1980s? The consensus doomsday forecast of the 1990s is that runaway health-care costs spell the ruination of the U.S. economy.

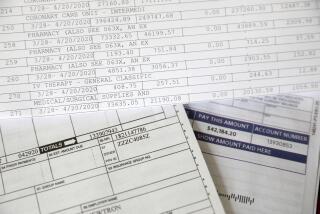

For all the partisan slanging in the Great Federal Budget Debate, both Newtoids and Clintonites take it for granted that federal spending has to be cut before it “gobbles up all savings and investment” as one liberal recently put it. And it is also taken for granted that the prime candidate for cutting is “runaway” health-care spending. Some scare estimates now show that, if allowed to continue unchecked, Medicare and Medicaid could consume up to 85% of private payrolls by the 2020s, when baby boomers will be in their dotage. Of course, nobody expects health-care spending to ever get that high--working people have to buy food--but it demonstrates the scale of the worries.

Such consensus warrants skepticism. For starters, it’s worth looking at the very premise that health care is “consumption” that strips resources from the “productive” private economy. Last summer, for example, economists were delighted when the Commerce Department reported that “industrial production” was rising--which certainly sounds like a good thing. In fact, all the increase was accounted for by growth in electric power output, because warm weather was pushing up air conditioning usage.

It’s worth examining what that means. Western coal was dug out of mines, mixed with huge volumes of water to make slurry and piped east and south. Huge tankers plied the oceans with oil. Giant turbines generated millions of watts of power. And, finally, cool air briefly wafted over lawyers’ sweaty brows. This we call industrial production. Cataract surgery, hip replacements and angioplasties we call consumption. “Industrial production,” in theory, makes us richer, “consumption” makes us poorer.

There is a brawny “good earth” illusion about “private” production. But the truth is that, distributional issues aside, Americans have pretty much all the housing and food they can use. The hot consumer products are Mortal Kombat, Doom II and interactive porn. Television, computer and telephone companies are investing hundreds of billions in the race to be able to pump thousands of movies into couch potatoes’ homes. The hot merger deals are in entertainment--the Bronfmans and MCA, Time Warner and CNN, industrial companies such as Westinghouse snapping up broadcasters like CBS.

Health care is supposed to be a low-productivity, low-wage industry. But that’s not true. Health-care productivity looks low on the official scorecards--but that’s because no one knows how to measure it. Virtually every professional basketball player, for example, almost as a matter of routine, has arthroscopic knee surgery at some point in his career. The operation is now so simple it is spreading among weekend tennis players.

Not long ago, a knee cartilage operation was major surgery, requiring opening up the entire joint. The risk of infection or other complications was high, and results were unreliable. Only a professional athlete with a career at stake would risk it. If we measured knee surgery the way we measure TV manufacture, we would say the productivity of knee surgeons has risen dramatically. They can do far more operations, much more cheaply and with much better results than ever before.

This is true for a host of procedures--laparoscopies to replace conventional surgery, lens and cochlear (hearing) implants, heart-valve repair, hip replacements, dissolving kidney stones with sound waves. All these treatments work. Do they make people any less productive than, say, Windows 95 software does?

Health care is now a high-tech industry. In high-tech industries where employees are responsible for large amounts of expensive capital equipment, wages tend to be high. Hospital worker wages are now about a third higher than the average worker’s. And hospital employment is one of the fastest growing sectors of the economy. Most years the growth in hospital employment exceeds the total employment in computer manufacturing. There is no other economic sector that offers comparable opportunities to young people without advanced degrees.

Better yet, most health care is not a tradable good. Starvation-wage workers in Malaysia won’t take away American jobs. And in the goods that are tradable, such as pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, America is a world leader, with a trade surplus of about $4 billion. And this is the industry we want to cut.

Is there waste in health care? Yes, of course. Should we crack down on unnecessary procedures and fraudulent billing? Absolutely. Will that stop rapid health-care cost growth? Not a chance. The simple fact is that old people need far more health care than younger people, and starting about 10 years from now, there will be far more old people in America. Investment in health-care research is high, and we keep producing new procedures and technologies that work--and that people want.

But the fears that health care will consume a disproportionate share of the economy are misplaced. Health care’s share of the U.S. economy will continue to grow, just as entertainment’s has. By the second decade of the next century, it will probably be as important as the automobile and automobile-related industries were in the 1950s. At some point--perhaps when health care equals about 30% of the economy, or twice as much as it does now--the inevitable bottlenecks will set in. Eighty-year-old baby boomers will have to hobble into lines for their knee replacements, because there won’t be enough surgeons to take care of them.

Most of health care’s bad reputation comes from using the federal government as a key financing mechanism. If the same spending were being funneled through some giant private insurance consortium, conservatives would hail it as an industrial triumph.

But we should be able to look beyond labels. Health care is a high productivity, good-wage, rapid growth, high technology industry, that creates lots more, and more useful, American jobs than making video games. It doesn’t make you fat like fast food, or fry your brain like cable television. There are tricky issues to be sorted out about financing mechanisms and burden sharing. But, as a nation, we can afford far more growth in health care. The real question is whether we can afford to slow it down.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.