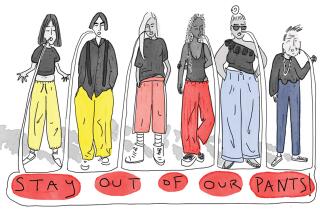

In India, More Women Are Wearing the Pants

- Share via

NEW DELHI — On a Friday morning, Monica Trikha, a 19-year-old honors student in English, rose from bed, peeked into her closet and did something her tradition-minded mother would never dare do.

She pulled out a pair of tight denim pants, slipped them on, and went to class.

“I wear jeans because they are comfortable,” says the raven-haired teen, who attends Jesus and Mary College in the capital. “Also, I see other girls wearing them, so I do the same.”

In the motherland of the sari, momentous changes are afoot in women’s clothing, changes that tell much about transformations in the status of India’s 450 million women and girls and in society itself.

“Basically, it’s the liberation of the Indian woman that is taking place,” says Ritu Beri, a New Delhi designer.

Suneet Varma, another top-ranked couturier, observes: “What’s changing? Pretty much everything.”

Nowadays, the urban Indian woman of means has more choices, in career and lifestyle, than ever. And her clothes are beginning to mirror that. “There are no rules,” Beri says. “It’s more about wearing what you feel is comfortable.”

At the same time, much of India, including the poor rural majority, remains unswervingly faithful to the sari, the unsewn swath of cloth, measuring 13 to 26 feet long by about 4 feet wide, meant for draping around the female form.

This quintessential women’s garment, also worn in Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, is alluring enough for the Bombay film goddess but so practical that a poor ditch-digger can wrap it between her legs to make pants.

The sari developed in part because of religious tenets; for Hindus, garments cut or pierced by metal needles were impure. For most Indian women, there’s no question of forsaking attire with a 2,000-year pedigree.

“Western clothes are just not, well, if the word isn’t ‘decent,’ then it’s ‘appropriate,’ ” says Nitu Malik, a New Delhi office worker and mother of two who is in her 30s. A woman who takes great pride in her appearance, Malik has 50 saris--and no jeans.

Even to many city-dwelling Indians, pants on a woman broadcast a message of licentiousness, says Swati Bhattacharjee of Calcutta. Wearing jeans on a crowded bus invites “preying hands,” she wrote in a recent newspaper opinion piece on women and contemporary fashion. Other passengers cast their eyes down in modesty, thinking, “If a woman can wear jeans, what can she not do?”

Saris still account for no less than a quarter of all textile production in India. But, nearly five years into reforms designed to open up India to the outside world on unprecedented scale, women’s wear is becoming much more diverse.

The reasons are many, says Rajiv Goyal, outgoing fashion editor of Clothesline, a leading industry magazine: more disposable income, women’s growing independence bestowed by education or a job, the influence of such TV shows as “Beverly Hills, 90210” and “Baywatch,” now beamed in via satellite.

“What’s going on in India now is like what happened in America in the ‘80s,” Goyal says.

*

But there’s more to this fashion revolution than a Western wannabe look. India, home of the pajama, jodhpurs and other styles that have become part of the world’s fashion repertory, is also rediscovering its heritage.

Beri, 28, a rising fashion industry star and a member of the first class at the National Institute of Fashion Technology, has devised entire lines based on the maharanis, or queens, of India, Buddhist motifs and Indian culture. She revels in her Indian-ness. “So many designers I know have been inspired by garments and motifs here,” she says.

Even long-standing habits of dress imposed by ethnicity, class or caste are loosening. In south India, the traditional half-sari is giving ground to the salwar kamiz, a long tailored tunic and gathered, billowy pants that were once the hallmark of Muslim women in north India.

Hindu brides customarily wear bright red. Now, some are wed in white--in India, the color of widow’s weeds. And, when the nation’s top movie actress, Madhuri Dixit, appeared in a recent wedding scene in a purple sari, thousands of Bombay brides yearned for the same.

“It used to be, either the Indian woman only wore a sari or salwar kamiz,” says Varma. “Nowadays, she can wear a long tunic, with flared pants, a short tunic with straight pants, or a blouse and sarong.”

A skeptical Goyal believes that no more than 1% of the population has been swept up in such novelties. But in India, fashions and fads have a way of seeping down even to the poorest through the movies. In fact, today’s archetypal middle-class sari, with a clinging blouse, long petticoat and fine, sheer drape tied in the nivi style of the Dravidian south and western Deccan, was popularized by Bombay film studios.

*

India’s new “flaunt it” attitude comes on the heels of nearly half a century of go-it-alone state socialism. A score of couturiers, including Beri and Varma, have become cultural stars as a growing number of television shows hawk their creations to the public.

“We never had such a thing as fashion. It used to be something that happened abroad,” Goyal says. “Now the middle class finds it is a new way of glamour.”

That may mean a household decking out its leading female in one of Varma’s heavy velvet burgundy pajama suits, priced at about $1,500.

“Dressing today is much more about people showing their wealth--that they’ve arrived or made it,” the designer says.

With consumerism running rampant, India’s budding crop of fashion designers should find a wider audience, as well as imitators whose knockoffs will be affordable to more people. “The Indian woman now has found her bearings and is not following what she was told to as a child, that she should follow her husband and do what he told her,” Beri declares.

A different view comes from Prachi Singh, 19, a New York City-born classmate of Trikha’s who returned with her family to India 10 years ago. “I wore a sari only once--during my school farewell [graduation]--and that’s about it, but I will be wearing more of saris and salwar suits after I get married,” she says. “I think the dress code changes then.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.