What It Takes to Turn In Your Kin to Big Brother

- Share via

A psychiatrist who happens to be an anthropology buff tells the story of a nomadic Arab tribe in which women were responsible for the well-being of the tribe’s horses. If a man abused a horse, his woman was expected to inform the chief. If she did so, however, her man was likely to beat her for disloyalty. But if she failed to inform against her man, and the chief found out, then the chief was likely to beat her for disloyalty to the tribe.

In psychology, this dilemma is a “double bind.”

In popular culture, it is a “Catch-22”--a no-win situation.

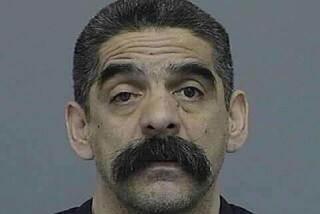

And it is also, one imagines, the special hell David Kaczynski occupies, having alerted the FBI, with thunderous repercussions, to his suspicions that his brother Theodore may be the long-sought Unabomber.

David Kaczynski, presumably a man with an admirable conscience, had a terrible choice to make once he started charting the similarities: Rat out his big brother or bear the burden of possibly failing to prevent any further mail-bomb mayhem. No matter what he chose, he would pay one of two steep prices: guilt or exposure.

Not such a tragic choice, really. Guilt corrodes you from the inside out. But exposure? Well, that eventually fades as reporters and photographers decamp in due course to the next disaster.

So, while the hell of guilt is eternal, the hell of media attention--hideous in the moment--at least is fleeting.

Still . . . would you have turned in your brother?

*

All families have codes of silence.

Sometimes they are explicit: Don’t tell anyone that Daddy hits Mommy. Don’t tell anyone that Mommy drinks until she passes out. Sometimes they are passed unwittingly from generation to generation, handed down in the form of taboos against expressing anger, joy or unpleasant truths.

Codes of silence, like rules, are remarkable only when broken.

Sometimes the code is ruptured by someone not quite in the loop yet--a child, say, reminded so often in school that drugs are bad that when she sees her parents smoking crack, she picks up the phone and dials 911.

Sometimes, the motivation is financial. David Kaczynski apparently did not know that a $1-million reward had been offered in connection with the Unabomber’s apprehension. Not so the relative of a thief who had robbed 18 branches of the same Southern drugstore chain. The relative turned in the miscreant to cash in on a $10,000 reward.

Sometimes the code gives way when a higher, conflicting family priority collides with the need for secrecy. Barbara Walker, ex-wife of spymaster John Walker, turned in her former husband not because she thought his spying was so bad (she had known about it for at least 17 years), but because her ex-son-in-law tried to use his suspicions about John Walker’s activities as leverage in a custody fight.

Grandma didn’t take kindly to that, so she beat him to the punch, thus helping her daughter regain custody of the child. What eventually bummed out Barbara was not that her ex-husband went to jail, but that her son did as well. She’d had no idea that Junior had been in the espionage business with Dad.

While it’s difficult to imagine parents (wittingly) turning in children, it’s hardly a stretch to picture siblings squealing, given their natural antagonisms. (When informed of the investigation of her son, Kaczynski’s mother reportedly expressed “the belief that Theodore was not the Unabomber, but if he was he must be stopped.”)

In many families, rivalry is the primary form of interaction between siblings: She hit me! No, he hit me! etc. This universal truth led one psychologist to joke that turning in your brother and getting a million bucks is the ultimate act of sibling rivalry: I’m telling the FBI on you. Nyah, nyah, nyah.

*

In the end, the person who takes such an anguishing step jettisons the family good for the greater good.

For most, this is no easy journey.

The psychiatrist who told the story of the Arab women says the reluctance to turn on a relative has to do with the “fundamental bondings” that allow us to survive infancy. “There is no way for a human being to get through infancy without the most virtuoso nurturing,” says Dr. Roderic Gorney, UCLA professor of psychiatry. “This is why we remain so dependent on attachments throughout our lives,” even when they cease to be physically necessary.

“When you are called upon to violate that kind of bonding setup, it becomes a tremendous strain.”

How, I wondered later in a conversation with a New York therapist, would you treat someone’s angst over having turned in his brother as the suspected Unabomber?

“Well, for starters,” he said, “I’d tell him not to open any gifts he sends you.”

* Robin Abcarian’s column appears Wednesdays and Sundays. Readers may write to her at the Los Angeles Times, Life & Style, Times Mirror Square, Los Angeles, CA 90053.