The Ties That Bind

- Share via

Americans don’t like to think of themselves as belonging to others. That is not a democratic idea. We are the country that invented self-invention. We like to believe we can be anything we choose--even if this means choosing what we define as family.

When being introduced, we rarely use family names anymore. Just a generation ago, even in California, it would have been rude for a friend to introduce me as anything other than “Mr. Ventura”--a name that comes, in my case, from a small village near Palermo, Italy, and carries with it the history of that place. Until recently, the name you met the world with wasn’t merely your own, it was also that of your ancestors--your bloodline walked with you into the world. A new acquaintance had to ask permission to address you by your Christian instead of your family name. The asking and giving of this permission was considered an important stage in the ritual of friendship.

Now, with family denigrated in importance, you are usually introduced by an unattached first name, a name that doesn’t speak of where you came from or who your ancestors were. In social intercourse, your past is abandoned. It helps reinforce the illusion that all we have to do to leave our family is to leave home.

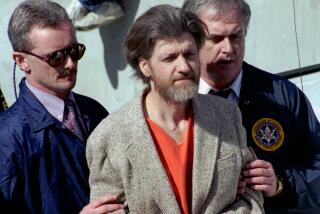

But what if the Unabomber is your brother?

What if you’re David Kaczynski, and you have good reason to suspect that your older brother, Theodore, has wounded or maimed 23 people, killed three and has even threatened to blow up airplanes--airplanes that could be carrying children? Then, the new ways fade and the old ties become excruciatingly real--in the name of your family, you must face what your brother has not: the innocence of the dead. Your brother, your blood, flesh of your flesh, could be the person killing people who in no way have merited such a death. It has become a family affair--and we all know how unreasonable family affairs can be.

To be David Kaczynski is to be faced with a moral dilemma both terrifying and unavoidable: Do you or do you not give up your brother? Either way, you live the rest of your life under the shadow of a guilt that no one but you can gauge or bear. If you rat on him, you will be part of the mechanism by which your brother may eventually be executed; if you don’t and he kills again, that blood will be on your hands. Either way, you, too, become a killer.

This is the kind of situation the word “tragic” was invented to describe--for tragedy occurs when the stakes are life and death, and every available choice is devastating.

If you are David Kaczynski, then you are thrust face to face with a truth that our contemporary discussions of family avoid: As members of a family, we are inextricably involved with each other, no matter how far we go to avoid that involvement. The very lengths some go to distance themselves from their families testify to the power of family bonds.

For whether we’re speaking of “family values,” the disappearance of the nuclear family or the emergence of the single-parent family; whether we’re discussing the legitimacy of “a family of friends” or of gay families--our arguments tend to be technical, legal, bloodless. As a culture, we seem to have forgotten what David Kaczynski has been forced to remember: To be family is to be inextricably implicated in the moral choices of our kin.

No psychologist can talk us out of the bone-deep feeling that if my brother kills, something in me is a killer; if my brother goes insane, something in me may be mad; if my sister dies, something in me dies; if my sister deserts her family, something in me may be a deserter. The only way not to feel this is to harden our hearts. And again, the extent to which we must toughen ourselves against some family members measures the depth of the bond.

The Kaczynski family teaches us that this is true no matter how great the estrangement of a family member. No one could have been more estranged from his people than Ted Kaczynski. He lived more than a thousand miles from his brother and mother, without a telephone, in a tiny shack in the wilderness. Apparently, he didn’t even read most of their letters, because he demanded that if they were writing of an emergency, they should underline the stamp with red ink. Clearly, those are the only letters he felt obligated to read. His family sent him such a letter when his father committed suicide (because of cancer) in 1990. Ted wrote back in anger, saying the death of his father did not constitute an emergency. This is estrangement with a vengeance.

Yet, the moral dilemma that Ted’s brother felt brought them close--no matter how much distance was between them. David had to do something or nothing, and either choice would steep them in guilt. For we may have the same choice with a friend or a lover; we may suspect them of terrible things, and have to choose silence or action. But who is so soulless as to claim that the guilt in such cases has a different weight? Who, reading of the Kaczynskis, doesn’t feel some shock that David turned in his brother? And isn’t that shock the true indication of what we really think of family--as opposed to what our superficial beliefs may be?

We may believe David was justified, but that is different from believing he was right. There was no way for David to be entirely right. In this tragic situation, any choice he made was bound to be part wrong, bound to make him guilty, in his own eyes and ours. Not that we blame him. In a sense, he acted on our behalf. Still, we do not trust him. No one will ever wholly trust someone who turned in his own brother.

And, it is likely he will never wholly trust himself again.

Reportedly, David tried to save his brother by striking a deal with the FBI that he would only give his information if Ted didn’t get the death penalty, if convicted. It was a desperate ploy. An intelligent man, David must have known that once he told anything, he’d have to tell everything. If he didn’t, he could be charged with obstruction of justice, or even arrested as an accessory. When the FBI refused to deal, David gave his information anyway. Thus, he is his brother’s saddest victim. For whether or not Ted Kaczynski is the Unabomber (and that’s for a jury to decide), David has turned in his brother. Nothing can change that. And, in the process, he has taught us how, in spite of all our rationalizations, family still has the power to entangle us, to enmesh us in one another’s fates.

The Kaczynskis have shown us that a brother, a father, a sister, a mother, can mark us even from afar--and change our lives utterly.

Not long ago, I had dinner with my brother, Vincent, for the first time in years. We live 3,000 miles apart, and we’re both obsessed with our work and our lives, so we see each other rarely. How good it was to sit across a table and look into one another’s eyes. We lifted our wine glasses, clinked them, and I said, “Blood on blood, Vinnie.”

“Blood on blood, Mike,” my brother answered.

We both knew where those words came from: Bruce Springsteen’s “Highway Patrolman” on the “Nebraska” album: “Me an’ Frankie, laughin’ and drinkin’/ Nothing feels better than blood on blood.” The song tells of a cop whose life is ruined when he lets his brother escape from a murder scene. “When it’s your brother, sometimes you look the other way,” Springsteen sings.

Sometimes you can’t, as David Kaczynski couldn’t. The power of family is the power to force us to such choices. Most are lucky enough not to be put to that test, but still that power is implicit in the family bond. What happens to my brother in some sense happens to me. No amount of rhetoric can erase that, no matter how far apart we live, or how well we hide.*

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.