Maya King’s Tomb Thrills Archeologists

- Share via

His kingdom wasn’t much to behold--a declining city-state in its last gasps of power.

For a king, he wasn’t much to behold either. Only 5 feet 2, he had once suffered a broken neck and mysteriously lost all his teeth before he died, perhaps at the unusually young age of 35.

His people apparently had neither the resources nor the desire to commemorate him with a temple or even a marker.

But when archeologist Norman Hammond recently found the tomb of this second-rate king from a third-rate city beneath the plaza of La Milpa in Belize, he became larger than life.

The tomb of the ruler called “Bird Jaguar” was the first unlooted tomb to be found in the region and one of the very few from the Maya empire to survive about 14 centuries of ravaging by thieves and vagabonds.

As such, it promises to tell a great deal more about the burial practices and beliefs of the people who developed one of the Western Hemisphere’s most noted pre-Columbian civilizations.

“Royal tombs in the Mayan area are uncommon, and unlooted ones are rarer still, so we were very excited to find this,” said Hammond, a Boston University archeologist who will announce the discovery at the British Museum in London today.

La Milpa lies just inside the western border of Belize, about 15 miles east of the much better known Mayan city of Rio Azul in Guatemala. Maya kings first sat at La Milpa around 200 AD and ruled continuously until the city mysteriously disappeared around 500 AD, about 50 years after Bird Jaguar’s burial.

The city was in a sharp decline when Bird Jaguar ruled, Hammond said, but it made a remarkable comeback about 700 AD. It ultimately was deserted when the Maya empire died around 900 AD.

La Milpa was built around a five-acre great plaza, which held two football field-size courts for the Maya’s sacred ballgame. It was surrounded by four pyramids.

Digging on the plaza, Hammond’s team found layers of limestone and flint chips, which turned out to be filling for the shaft that led down to the burial chamber. The tomb, which Hammond said was “about the size of a Volkswagen Bug,” was carved out of solid rock about 10 feet below the surface. The fact that it was unmarked, Hammond said, suggests that Bird Jaguar was “a petty king, bus league.”

The Maya did not practice mummification or other techniques of bodily preservation, so all that was left of Bird Jaguar was his skeleton. But that skeleton was unique.

Healing scars on Bird Jaguar’s jawbone indicate that all of his teeth had fallen out before he was buried. “There was not a tooth in the tomb,” Hammond said.

“Whether this was genetic or some sort of disease or he was an unwise eater, we don’t know. But it’s very unusual to find a Mayan without teeth. Often the teeth are the best preserved parts of the body.”

The king’s neck had also been broken at some point. The vertebrae had healed before he died, but the injury had clearly been serious, Hammond noted. Another sign of possible ill health was the fact that the king “died rather young,” he said, sometime between the ages of 35 and 50. Most Maya rulers lived beyond 60 and at least one lived to 90.

His jewelry was even more intriguing.

“He was wearing a jade necklace of beautifully colored and matched apple-green jade with this pendant in the form of a vulture head hanging from it,” Hammond said.

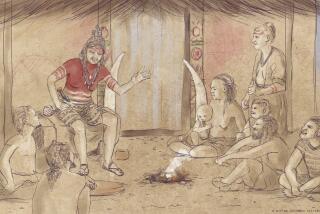

The vulture head was used by the Maya as a symbol of royalty, who were regarded as divine. “He was the conduit to the gods and the other world in his lifetime, and deified and venerated as an ancestor and a god after his death.”

A separate bead of jade, the size of a cherry, was placed in his mouth, probably as a receptacle for his spirit. The jade was mined more than 250 miles away in Guatemala.

The jade pendant is “a really superb piece . . . a unique piece of Maya lapidary art,” Hammond said, and far more impressive than the ear ornaments and other jewelry he wore. “That was second-grade stuff.”

Bird Jaguar was among the first Maya kings to undergo ceremonial burial, a practice that began around 400 AD. As such, artifacts in the tomb may yield unique insights into the evolution of their religious beliefs.

But that early date may also explain the lack of markers and the small size of the tomb, Hammond said. The Maya just may not have been good at elaborate burials yet.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.