Do You Greet the World on High or Keep It Low-Key?

- Share via

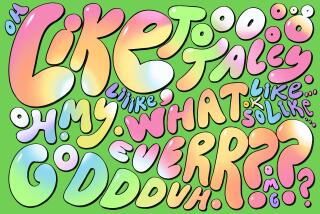

Walk into a soiree where women and men are making the rounds and hear a striking sex difference: Women greet each other in a high-pitched, singsong voice stretching the words multisyllabic: “Hi-i-i-i-e-e-e-e. H-o-o-o-w-w-w are you d-o-i-i-n-n-g-g?”

Men do the reverse. Voices dropped to basso profundo, they curtly nod and say, in staccato grunts: “Hey, hey. How ya doin’? What’s up, man?”

The distinctions are the behavioral equivalent of “Me Jane.” And “Me Tarzan.” The difference also reflects the most fundamental variance in the ways that women relate to the world (I just wanna be a girlfriend) versus the way men do (Go ahead, make my day) and are deeply embedded in our evolutionary psychology, experts say.

As in most forms of communication, women focus more on connecting, emoting and overtly showing affection. Men are busy establishing the pecking order, reining in their emotions, maybe throwing a mock punch or a friendly insult. The handshake, popular among American men and less so among women, is said to be the peak of male bonding: the point at which he-man overcomes the urge to defend personal space. The 200-year-old gesture’s original function was to show the absence of weapons.

Linguists agree that “the greeting ritual” is an automatic trait rooted in “gender marking,” a characteristic drummed into us and probably prevalent through the ages. The “feminization” or “masculinization” of the voice is exaggerated during greeting, say linguists, because meeting or reuniting with someone is “one of the most difficult moments” in human relations.

“The elaborate greeting ritual women use is to reestablish the connection, so that the longer they have been apart and the closer they are, the more heightened the voice would be,” says Deborah Tannen, a linguist at Georgetown University and author of “You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation” (William Morrow, 1990) and “Talking From 9-to-5” (Avon Books, 1994). “The high pitch shows endearment and attachment. They lean in toward each other, which is part of the same pattern of communication of talking to each other face to face. Men tend to sit at angles and look around the room.”

Tannen thought herself immune to such girlie-girl displays until she bumped into some old high school chums at the New York Linguistic Institute years ago. Before she knew it, the group was shrieking in glass-shattering octaves, overjoyed at the serendipitous reunion. The experience mimicked a scene in “Splendor in the Grass,” she says, where Natalie Wood reconnects with high school girlfriends, who hold hands, jump around and scream in a frenzy of ecstasy. (Her husband looks on as if he has witnessed an extraterrestrial ritual dance.)

But such voice lessons are engendered long before high school.

“Kids learn by imitating,” says UC Berkeley linguist Robin Lakoff, author of “Talking Power” (Basic Books, 1994). Little girls are taught to show positive emotions, endearment and affection with high-pitched voices, and boys learn to express negative emotions using deeper voices to sound big, strong and threatening.

“Practically the first thing children know about each other is who is a little boy and who is a little girl,” she says. “When they acquire language, they learn how little boys and how little girls should talk.”

Jean Berko Gleason, a Boston University linguist, found in her studies that parents speak differently to girls and boys, imparting a different set of sounds for each sex to imitate. Both parents, but especially mothers, speak to little girls in softer, less stern voices and use more diminutives (sweetie facey, look at the itsy bitsy buggy) than with little boys (hey, Godzilla face, how ‘bout a nice rare buffalo burger for lunch?). From anecdotal evidence, she says, it appears that the smaller the child, the higher the parent pitches his or her voice.

But the gender differences in voice tone are present only in greeting. “When regular conversation resumes,” Lakoff says, “we go back to normal voices.”

The greeting moment is an anxious one.

“You go through this, ‘Will they be happy to see me? Will they be competitive? Are things OK between us?’ ” Lakoff says. “When you are anxious, you exaggerate your defenses . . . go back to the appropriate childhood niche, behave according to your gender. If you are a woman, infantilizing the voice says, ‘I won’t harm you.’ Men deepen it to say ‘Don’t make trouble for me.’ ”

The voice pitch each sex uses also has to do with “sound symbolism,” the theory that we use a smaller (high-pitched) voice for smaller, vulnerable things (puppies, kitties and babies) and a deeper, louder voice for larger things (Great Danes, he-men, bulldozers).

But what about decades of the women’s movement liberating us from the silly constraints of sex typing? If we got rid of the girdle (OK, so it’s sneaking back into our closets re-marketed as body restructuring undergarments), why can’t we stop greeting each other in baby-speak?

“You can’t override a thousand millennia in 25 years,” Lakoff replies.

Even in caveman times, Lakoff speculates that voice tones were used by the sexes for much the same purposes: Women used it to reconnect as gal pals, critical when sharing cramped cave space with limited resources. Men used it either to bond with allies or ward off interlopers.

In other words, when that popular prehistoric pair Betty and Wilma were reunited after time apart, one probably said to the other: “H-i-i-e-e-e-e, cave gal. You look f-a-b-o-o in that new hide. Get you some berry tea, hon?”

And Fred probably had Barney in a head lock.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.