Williams Was Able to See the World, 400 Meters at a Time

- Share via

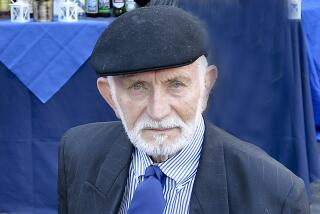

Michael Johnson is the world’s top runner at 400 meters, but 34 years ago, that honor went to Ulis Williams, a lanky sensation from Compton.

At 17, Williams set a national high school record at 440 yards (46.1 seconds), then finished a close second to Otis Davis, the 1960 Olympic 400-meter champion, in an international meet shortly after graduating from Compton High in 1961.

Whenever Williams ran, crowds came to watch, just as they do for Johnson today.

Al Wolf, a Times columnist in the early 1960s, called him the “Compton Comet” and wrote that Williams was a world record ready to happen every time he ran.

“Ulis was just a phenom in high school,” said USC track and field Coach Ron Allice. “He had such a long, smooth stride. He was a graceful athlete to watch.”

For nearly four years, Williams, now interim president at Compton College, dominated his competition while running for Arizona State. In 1962 and 1963, he was ranked No. 1 in the world by Track and Field News at 400 meters and was No. 2 in 1961 and 1964.

At the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, Williams won a gold medal on the U.S. 1,600-meter relay team that established a world record in 3:00.7. He finished fifth in the 400, still not at peak form after suffering an upper leg injury at a meet four months earlier.

“There is no doubt that track was great for me,” said Williams, who grew up picking cotton in Mississippi. “It enabled me to travel throughout Europe and other places in the world. It was a surreal kind of experience because I never had dreams or any aspirations to be that good running track.”

The sport was different then. Johnson can earn millions of dollars from running, but Williams had to pursue a career off the track soon after he won his gold medal in Tokyo.

Does he regret not being able to cash in on his track success?

“That is not reality,” said Williams, who earned a bachelor’s degree in recreation and physical education at Cal State Los Angeles and a master’s in urban studies at Antioch College in San Francisco after the ’64 Games.

“You cannot compare because you are talking about two different eras. I appreciate the time I had to compete.”

Williams started up the administrative ladder at Compton College in 1972. It’s a far cry from the jobs of his youth.

“I grew up on a plantation in Hollendale, Miss., with my mother, two brothers and three sisters, and we worked as day hands,” said Williams, who became the first in his family to graduate from high school. “I did not move to California to live with my father until I was 15. The only pressure I felt at that age was to just emulate someone in my family.”

When Williams moved to Compton in 1957, he soon learned life was different from the one he had known while picking cotton in Hollendale.

“I was really uncomfortable when I moved because I had to deal with uncertainty,” he said. “I didn’t have confidence, and I had trouble coping at first. . . . Things were so different for me.”

A turning point came in a junior high gym class when he beat the then-fastest kid in the school in a 660-yard run. The next fall, Williams was recruited as a freshman by Compton High’s track coach, Fred Kennedy, to run on the cross-country team as a prelude to his first outdoor track season the next spring.

“I really didn’t know anything about track,” Williams said. “I didn’t even know who Jesse Owens was. When [Kennedy] asked me to come out for the cross-country team, I thought it was to study nature things.”

Williams became a respectable cross-country runner. But his ability to run the quarter-mile put him in a class by himself.

“It was easy to tell that Ulis was a special runner,” said Baldy Castillo, the Arizona State coach who began recruiting Williams during his junior year. “You knew that he had ability.”

At Arizona State, Williams ran the anchor leg and teamed with Henry Carr, Ron Freeman and Mike Barrick to set a world record in the mile relay in 3:04.5 in 1963.

“That was a special group,” Castillo said. “From the first time they ran together, I felt that they would set records. But when they set a world record, I was even surprised.”

Williams ran in only a few meets after the Olympics before leaving the sport, returning to Southern California and completing his education. He started at Compton College as a part-time physical education teacher and track coach.

He led the track team to a conference championship and had several individual national champions. Williams became athletic director and, in 1983, was named associate dean of continuing education and community services, which has led to his current position as interim president.

“Ulis has been on our campus for over 20 years,” said Carl Robinson, president of the school’s board of trustees. “It’s great having him here, because he’s known throughout America from his track exploits and he’s well liked on our campus. He’s doing a great job right now.”

Williams will not know until at least November if he is to be named permanent president because of a community college rule that requires Compton to conduct a nationwide search.

But that has not stopped him from helping the college gain its first full accreditation this decade and raising the school’s enrollment to 6,000 students after being down to almost 4,000 only a year ago.

“There is such a rich history here at Compton College that most people do not know about,” said Williams, a charter inductee in the Arizona State sports hall of fame. “I love what I’m doing because I love working with people. I like to be in position where I can try and make a difference.”

Williams’ goal is to help keep enrollment on the rise and for Compton College to continue to improve its facilities and curriculum.

“I know that it is going to be a slow process,” Williams said. “But if I felt that I couldn’t make a difference, I wouldn’t be here. Every area that I’ve been responsible for on this campus, I’ve been successful. And that was only because I’ve always believed that hard work does pay off. That’s the only way I know.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.