True Colors : Biotech Company Calgene Patents Gene to Control Cotton Pigment

- Share via

Yearning for a pair of indigo jeans or a black T-shirt that won’t fade?

That dream might become reality in a few years. Calgene Inc., perhaps best known for its introduction two years ago of a genetically engineered tomato that failed to live up to the company’s high expectations, said Tuesday that it has received the first U.S. patent covering a gene that controls pigment in cotton.

Such technology, which Calgene cautioned is in a very early research stage, holds the promise of cost saving for textile companies that now invest enormous amounts of time and money in dyeing cotton.

“Mills today spend 10 to 90 cents per pound dyeing their products, and they still don’t get true color fastness,” said John Callahan, senior vice president of business development at Calgene, based in Davis, Calif. “We can give them total color fastness.”

Callahan, who noted that the textile industry also must spend heavily to dispose of toxic dyes, said true color fastness could open up significant markets not only in apparel, but also in carpeting and floor coverings. Companies in that industry use more than 3 billion pounds of fiber annually, almost none of it cotton. In the U.S. apparel industry, cotton now accounts for more than 60% of clothing, up from about 30% two decades ago.

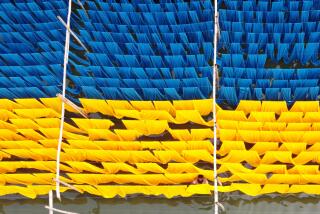

Calgene’s fledgling technology entails injecting a gene from melanin, a dark brown or black pigment found in bacteria, into cottonseeds of the Upland Picker variety. Also under development are blue and red tones.

The colored cotton is being developed with Calgene’s Stoneville Pedigreed Seed Co. in Stoneville, Miss., the nation’s second-largest cottonseed company. The company manages the growing and ginning of cotton from 60,000 acres in the Mississippi Delta, Arizona and the Southeast.

In California, where white cotton is a $1-billion industry, the growing of colored cotton has long been controversial. Sally Fox, a plant breeder who in the early 1980s began growing colored cotton near the San Joaquin Valley town of Wasco, learned this the hard way.

To defend its reputation for growing some of the best cotton in the country, California has a strict “one-variety” rule that is enforced by the San Joaquin Valley Cotton Board. That regulation lets the established growers who sit on the board use the force of law to forbid competitors to grow any cotton other than the Acala variety, known for long, strong fibers that spin easily into thread. Growers of white cotton maintain that fields of colored cotton would pose the threat of accidental contamination.

In 1990, the state denied Fox’s petition to begin growing her brown and green cotton in commercial amounts; she eventually took her tiny operation to Arizona.

Other colored-cotton breeders, including B.C. Cotton Inc. in Bakersfield, have sued in an effort to win the right to grow in commercial quantities. The cotton board prevailed in one suit filed by the breeders in Superior Court in Sacramento; the opening hearing in a federal suit is set for Dec. 2, according to Bob Dowd, an attorney for the cotton board.

For investors, Calgene has proved to be a test of patience. The company’s genetically engineered Flavr-Savr tomato, introduced with great fanfare in 1994 under the MacGregor label, failed to live up to expectations because the tomatoes did not hold up well in the handling process.

A year ago, Monsanto Co. agreed to buy half of Calgene, providing much-needed cash and a link with Monsanto’s Gargiulo produce company in Naples, Fla., the nation’s largest tomato packer. Calgene and Gargiulo are working to develop a good-tasting, genetically engineered tomato that can hold up to the rigors of commercial distribution.

Calgene is also developing edible plant oils and insect- and herbicide-resistant cottonseed.

One observer said the prospect of bioengineered colored cotton should hearten Calgene’s beleaguered stockholders.

“I’ve always thought this was one area that justifies investors’ patience,” said John McCamant, associate editor of the AgBiotech Stock Letter, a newsletter based in Berkeley.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.