Deng Never Lost Sight of Goal to Reform Chinese Economy

- Share via

BEIJING — Deng Xiaoping, who died Wednesday at 92, brought pioneering economic reforms and an unprecedented prosperity to China but ruthlessly resisted efforts to change the country’s political system.

He was last seen in public in Shanghai in 1994, frail and disoriented, although his latest significant contribution to China’s politics had come in 1992, when he traveled in the south of the country urging acceleration of economic reforms. Proof of his continuing influence--even though he held no official position at the time--the “southern tour” speeches revived the stalled Chinese economy and sparked a new surge in China’s growth.

In recent years, Deng’s health was in steady decline. Rumors periodically coursed the narrow lanes of the Chinese capital that he was dead or dying. Visitors said he was no longer able to stand or feed himself. His only title was most honorary chairman of the China Bridge Assn., a tribute to the card game he mastered as a young revolutionary.

Deng’s family said he was kept alive by one final goal--his wish to see Hong Kong restored to Chinese rule in July.

“I’m willing to live until 1997,” Deng said in his collected works. “Then I will see China assume its sovereignty over Hong Kong with my own eyes.”

When Deng gained control over the Chinese Communist Party in 1978, he was seen as the antithesis of Chairman Mao Tse-tung, the leader of the 1949 Communist revolution who had clung to power for 27 years.

Unlike Mao, who emerged from China’s peasantry and never visited a Western nation, Deng saw the wealth of the capitalist world firsthand as a young man in Paris. He spent the rest of his life fighting to lay the foundations for modernization in China.

“Whether a cat is black or white makes no difference,” Deng declared in the early 1960s, during a fight with Mao over economic policy. “As long as it catches mice, it is a good cat.”

The twin themes of the Deng era were captured in policies set by the late-1978 party meeting that entrenched him in power: market reforms, including opening up to the outside world, paired with unyielding dictatorship by the Communist Party.

Deng launched China on a new course of economic pragmatism that stood in marked contrast to Mao’s radical egalitarianism.

Deng quickly abolished Mao’s rural communes and let peasants cultivate family plots. China’s grain output shot up. He allowed Chinese city dwellers to engage in small-scale private business, opening the way for the sort of entrepreneurial hustling that under Mao would have been denounced as “the tail of capitalism.” People were permitted to buy consumer goods that most Chinese had never possessed--television sets, refrigerators and increasingly fashionable Western-style clothes.

‘Three Big Things’

As a result, most Chinese are now much better off materially than at any time in modern history. Twenty years ago, consumers in China wanted to acquire the “three big things”--sewing machine, watch and bicycle. Now these possessions are so universal that they are no longer listed in consumer reports. A Chinese wish list is now more likely to include a microwave oven, a car or an apartment.

In 1978, when Deng first came to power, fewer than 1% of Chinese households had television sets. By 1995, the number of urban households possessing color television sets approached 90%. In 1978, there were virtually no privately owned automobiles in China. Now, the number of privately owned cars has reached 2.5 million, and in major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, sales of cars to private owners have surpassed those to government work units.

Under Deng, China had gone from a collectivist to a consumer society. The world’s great corporations vied for a piece of the giant Chinese market. The material improvements brought new freedoms to much of the population.

“For most urban Chinese,” wrote the historian Tony Saich, “the changes have been significant in terms of choice of work and lifestyle. Anyone under 35 has known only a time of discussion about reform and increasing contact with the outside world. Despite restrictions, there has been a steady advance toward increased liberty for a majority of urban Chinese.”

Yet, during his time in power, Deng failed to bring about accompanying changes in the Leninist political system that Mao and other Communist Party leaders, including Deng himself, created in the early years after the 1949 victory.

Like Mao before him, Deng clung to power, despite becoming less mentally sharp in his final years.

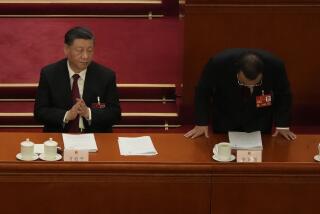

However, by February 1994, when Deng attended a gathering at a Shanghai hotel, his condition had visibly deteriorated.

Only two years before, he had managed the rigorous swing through the country’s south, delivering long speeches in several cities, lashing out at enemies and calling vigorously for continued reform. But by the time of his Shanghai appearance, televised to hundreds of millions of Chinese, his body had become a frail shell, his once-lively eyes hollow and vacant.

Tiananmen Legacy

A senior Communist Party leader, Chen Yun, once quipped after Mao’s death: “If Mao had died in 1956, he would have been considered one of China’s greatest leaders. If he had died in 1966, we could still have said that the good outweighed the bad. Unfortunately, he died in 1976.”

The same sort of statement might be made about Deng. If Deng had died in 1984, he would have been called one of China’s greatest modernizers. If he had died in 1987, the historical verdict on him would still have been almost as favorable.

But Deng lived on, and the events of 1989, when the Chinese army was used to crush the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests, left an ineradicable bloodstain on his record.

The demonstrations, by students seeking greater democracy and attacking corruption within the Communist Party, had overshadowed what was intended as one of the last great achievements of Deng’s diplomacy--a visit to Beijing by Mikhail S. Gorbachev, then president of the Soviet Union, to normalize Sino-Soviet relations. After Gorbachev left, with hundreds of thousands of Chinese in the streets supporting the student demonstrators, the Chinese regime cracked down. Presumably under Deng’s orders, the leadership put Beijing under martial law, and it called upon the army to help restore order with Deng’s strong approval.

Deng’s role in the final decision to send troops into Beijing was made clear during a recent 12-hour documentary on his life that appeared on China Central Television, the main national network. Looking determined and very much in control, Deng spoke in defense of the military intervention and installation of martial law.

At first, the Chinese troops pulled back when residents of Beijing, in an outpouring of “people power,” blocked the movement of their vehicles. But two weeks later, with pro-democracy demonstrators still occupying the center of Beijing, the troops moved into the city with murderous force.

Using automatic weapons and driving tanks at high speeds, the troops killed hundreds of people on the night of June 3-4. The victims included bystanders--not just students or rebellious workers but elderly women and small children. For days after that, People’s Liberation Army units roved through Beijing, firing indiscriminately.

The death toll may never be known, but Western intelligence agencies eventually settled on an estimate of 1,000 to 1,500 dead.

Regarding that incident, Deng was unrepentant.

“This time,” Deng said at a 1989 meeting following the crackdown, “our resolution of the turmoil by means of martial law was extremely necessary. In the future, if necessary, when factors leading to turmoil appear, we must take severe measures to wipe them out in order to ensure that our nation is not subject to external interference and to protect our national sovereignty.”

The world was shocked by the massacre. The famous photograph of a solitary man standing defiantly before a People’s Liberation Army tank became one of the icons of the modern age.

But the refusal to tolerate dissent and willingness to resort to force against any challenge to the Communist Party were consistent with Deng’s record. In 1957, while serving as Communist Party general secretary under Mao, Deng had spearheaded the “anti-rightist” campaign in which thousands of intellectuals were jailed or sent into internal exile.

Short-Lived Flowering

Deng initially consolidated his own power in 1978-79 by permitting the flowering of “Democracy Wall” in Beijing, not far from Tiananmen Square. Posters displayed there lambasted Deng’s enemies in an upsurge of anger over Maoist abuses. But he quickly turned against youths who took the opportunity to advocate real democracy. He ordered the wall shut down and sent the most famous democratic activist of that period, Wei Jingsheng, to prison.

During Deng’s final years, virtually all of China’s small corps of dissidents was imprisoned or sent into forced exile abroad.

Under Deng, the Chinese Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army, its military arm, remained the only institutions with political power. And China remained subject to the whim of one “paramount leader,” just as the nation had been under Mao, under Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and, before them, under imperial rule.

Soon after assuming supreme leadership, Deng had started trying to groom and install younger successors, picking Hu Yaobang as head of the Communist Party and Zhao Ziyang as premier. He pushed most of his elderly colleagues into formal retirement.

The death of Hu, who had been pushed out of his post as head of the party, had touched off the spring 1989 protests. The decision to spill blood to end the demonstrations, a course bitterly opposed by Hu’s successor, Zhao, led in turn to Zhao’s downfall.

Just five days after the June 3-4 massacre that ended the 1989 demonstrations, Deng declared that his economic reforms would continue.

But Beijing and much of China were caught in a paroxysm of political repression. The party’s first goal was reimposing control. New economic reforms were put on hold, although efforts to attract foreign investment and push forward with the modernization drive continued. Deng retreated further from public view, only to reemerge in early 1992 with his trip to the south.

Faustian Accord

Deng had struck what a European diplomat in Beijing described as a Faustian arrangement with the Chinese people. He had promised, and delivered, ever-increasing prosperity. But the price he demanded was popular acceptance of continued authoritarian rule.

Five years after the events of Tiananmen Square, it was a price many Chinese appeared willing to pay. Many of those who participated in the 1989 pro-democracy protests said they were now content to leave politics behind and concentrate on making money.

The effect of the 1989 massacre was to spoil or jeopardize much that Deng had set out to achieve--political stability, steady economic growth, firmer social progress, interchange with the outside world, broader international respect and a peaceful, orderly return of Hong Kong from British to Chinese rule. Moreover, the massacre made a mockery of the Chinese Communist Party’s claims to popular support.

Yet Deng carried on, still believing that China could be modernized under Communist Party rule. His leadership style was to maintain power through a combination of force and cunning strategy. His hobby was bridge. And, in domestic politics and international affairs, as well as at the bridge table, he always relished making the most of the cards he was dealt.

In foreign affairs, he leaned heavily in the late 1970s on the United States as a counterweight to Soviet military power. By the late 1980s, as the Soviet threat receded and Japan grew in economic and political strength, he moved to restore China’s links with the Soviets.

So too in the maneuvering within the Chinese Communist Party, Deng would veer left or right, seeming to favor younger reformers or the party’s elderly traditionalists, depending on the requirements of the moment.

He was a short (5 feet, 2 inches), chunky man with a panda-like face and a knack for blunt speech. “When your face is ugly, you should not pretend to be pretty,” he used to say.

Once, after Deng gave a characteristically tough speech, then-Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger referred to him as “that nasty little man.”

Other world leaders who came to visit him found themselves often in awe and regularly upstaged. In the few minutes in which television cameras recorded the meeting, Deng would manage to find some way to put visitors in their place.

When former President Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy, sat down with Deng for the first time in April 1984, the Chinese leader turned to her and quipped, “Next time, you come to China without him.”

When John J. Phelan, chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, came to visit, Deng cracked, “You know why we invited you here? We want to exploit you.”

Deng’s roots in the Communist Party were nearly as deep as Mao’s, and his revolutionary credentials were impeccable.

Prosperous Beginning

Born Aug. 22, 1904, in Xiaxiang village in Sichuan province in the southwest, about 65 miles from Chongqing, Deng was the second child of the second wife of a prosperous landowner.

Finishing school early, he was chosen in 1920 to join 90 young Chinese for study and work in France. The Manchus, the last of the imperial dynasties, had collapsed nine years earlier, and China was in its first hectic years as a republic. The Chinese students were to bring back ideas and skills for modernization.

In France, Deng fell in with young Chinese leftists led by Chou En-lai, later to be Communist China’s premier, and he helped print and distribute the political tracts written by Chou and others. Deng was awarded the mock title of “doctor of mimeography.”

Joining the newly founded Chinese Communist Party in 1924, Deng dropped his birth name of Xiansheng and adopted the name Xiaoping (Little Peace), following the Chinese custom of thus marking an important new phase in life.

He left France for the Soviet Union in 1926, attending lectures in Moscow along with Chiang Ching-kuo, son of Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek and later the head of the Nationalist government on Taiwan.

Returning to China, Deng was assigned by the Communists to party work and then as political commissar of Red Army units in Guangxi province in the south. A convert to Mao’s theories of protracted guerrilla warfare against the rival Nationalists, he was criticized by fellow Communists advocating conventional battle and was ousted from his post in 1933. It was the first of three purges for Deng.

Back in good standing a year later, Deng joined Mao in the Communists’ Long March, the epic, 6,000-mile fighting trek to escape Nationalist encirclement in the south. An American officer who met Deng in 1938 described him as “short, chunky and physically tough, with a mind as keen as mustard.”

The condiment metaphor was apt, for Deng had proved himself as a cook, as well as military commander and political commissar, turning whatever came to hand into tasty stews, including Mao’s favorite: dog meat in brown sauce.

Years of Warfare

In the ensuing years, the Communists fought first the Nationalists, then the Japanese invaders. With the end of World War II, the Communists and Nationalists resumed the civil war in earnest.

For Deng, the most important campaign was in 1948 and 1949, when he and Marshal Liu Bocheng led the forces that defeated 550,000 of Chiang Kai-shek’s best troops and broke Nationalist resistance along the Yangtze River.

After the Communist takeover in 1949, Deng was mayor of Chongqing in his native Sichuan before Chou called him to Beijing. He became vice premier, finance minister, a drafter of China’s new constitution and then general secretary of the Communist Party. Endless capacity for work, careful attention to detail and hardheaded realism marked his rise.

“See that little man over there?” Mao asked Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev in 1954. “He is highly intelligent and has a great future.”

Despite the praise, Deng often disagreed with Mao over China’s course. Deng acted with increasing independence as the party’s powerful general secretary, and Mao later was to complain that his subordinate treated him “like a dead ancestor.”

“Which emperor authorized that?” Mao demanded after Deng ordered collective land turned over to individual peasants to avoid deepening famine after the failure of the Great Leap Forward launched by Mao in 1958.

The extent of that famine has only recently been known. In the 1996 book “Hungry Ghosts,” British journalist Jasper Becker reported that more than 30 million people died, almost all because of the failed Maoist policies.

By standing against these policies, Deng was heading for a fall amid the economic problems and radical political currents of the 1960s. Urging major reforms, he proposed free markets for farmers, incentive bonuses for workers and broad authority for plant managers.

This break with Maoism made him a major target during the leftist-dominated upheaval of the Cultural Revolution. Along with President Liu Shao-chi, he was denounced as a “capitalist roader” and purged in 1966.

Assailed by Red Guards for his opposition to class struggle and continuing revolution, Deng confessed in a self-criticism written in late 1966 that he had come to oppose many of Mao’s policies and, far from “raising high the banner of Mao Tse-tung thought,” as party propaganda exhorted, “I have not even picked it up.”

Deng was held under house arrest in Beijing for two years, paraded through the streets in a dunce cap and made to wait on tables at a Communist Party school.

In 1969, he was exiled to Jiangxi province in southeastern China, where he worked for a time as a lathe operator, a job he had learned as a student in France. He, his wife, Zhuo Lin, and some of their five children lived in an abandoned infantry school outside Nanchang, the provincial capital. Deng did most of the cooking and chores, such as cutting firewood, one of his daughters has written. He spent his spare time gardening, playing checkers and reading.

“The Gang of Four [radicals led by Jiang Qing, Mao’s wife] had extraordinary power, and they wanted to kill me,” Deng recalled later. “Fortunately, I was protected by Chairman Mao . . . [who] supplied a personal security team for me.”

Deng was brought back from political oblivion in 1973 when Premier Chou tried to halt the Cultural Revolution and restore stability after seven years of virtual civil war. Deng was made senior deputy premier and soon added party and military posts.

Unchastened by his travails, Deng resumed his old ways.

“Go ahead boldly,” he told party officials in a 1975 speech pushing economic reform. “As long as people say you are restoring capitalism, you have done your work well. Don’t be afraid of opposition or being toppled. We already have been struck down once. Why should we be afraid of being struck down a second time?”

The result was predictable: He clashed with Mao and the radicals around the chairman.

Chou, who had been Deng’s patron, died in early 1976, and Mao passed over Deng to make the interior minister, Hua Guofeng, the new premier. Deng rallied his supporters, and when tens of thousands of anti-leftist demonstrators filled Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in April 1976, Mao and the radicals took it as a counterrevolutionary threat from Deng and purged him again.

Mao died in September 1976. A month later the Gang of Four, including Mao’s widow, were arrested and many radicals were purged from the party and government. “Bring back Deng” posters soon appeared; he was formally reinstated in July 1977.

It was late 1978 before Deng and his supporters won the struggle over policy and secured a working majority in the party’s top ranks.

As China’s dominant leader, Deng in January 1979 visited the United States, with which Beijing had just normalized relations. He massaged U.S. egos, dangled the prospect of lucrative business deals and tossed off insults at the Soviets.

Soon after his return to China, Deng launched an abortive invasion of Vietnam, withdrawing several weeks later after Chinese troops suffered heavy casualties.

Deng never took the title of chairman of the Communist Party. But he took and kept until late 1989 the most significant title that Mao had held: chairman of the Communist Party’s Central Military Commission, the man in charge of the People’s Liberation Army.

In the end, the absence of titles mattered little. To the world, Deng was China’s “paramount leader.” And by 1989, dissatisfied Chinese began sarcastically referring to Deng the same way as they had Mao--as China’s “emperor.”

Such dissatisfaction was not evident at first.

In the 1978-79 period, as Deng grasped the levers of power, there was exhilaration in the nation. Most Chinese believed that they were not only being freed from Mao’s mistakes but finally finding the way to make China a rich, powerful, modern nation. Deng quickly altered many of the Maoist policies that he believed had held back China’s modernization.

Opening China’s Doors

He opened China’s doors to the outside world. First hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands of young Chinese went abroad to study.

Foreign businesses were invited to come to China as Deng and his aides sought to obtain new technology and learn modern management techniques.

Deng also moved to achieve economic growth by limiting the number of new mouths the country had to feed. Soon after Deng took power, Beijing adopted new population-control policies, seeking to impose limits of one or two children per family.

Particularly in the countryside, the rules were unpopular and were sometimes enforced by coercion, including forced abortions.

Deng’s popularity in China peaked in 1984, after his first half-decade at the helm.

It was, for China, a glorious year. After five years of steadily increasing harvests, the wheat fields and rice paddies produced more than 400 million tons of grain, the largest output in China’s history, enough to make the often-hungry nation self-sufficient in food.

That same year, in foreign affairs, Deng won from Britain the agreement to return control over Hong Kong to China.

Former President Reagan, Taiwan’s oldest and strongest supporter among top-level American politicians, paid court in Beijing. At the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Chinese athletes did so well as to rekindle in China a proud spirit of nationalism.

On Oct. 1, 1984, the 35th anniversary of Mao’s founding of the People’s Republic of China, Deng rode through Beijing in a massive parade of floats displaying symbols of modernization and consumer goods. “Xiaoping, ni hao?” (“Xiaoping, how are you?”) shouted the crowds.

Pleased with the success of reforms in the countryside, Deng launched a new series of urban economic reforms. At a Central Committee meeting in October of that year, the Communist Party approved a landmark document embracing for the first time the idea that consumerism--the desire of the Chinese people for material goods--could help the nation achieve industrial growth.

“Socialism does not mean poverty,” the party said.

In mid-1989, following the upheavals in Beijing, Deng was forced to turn to a politically weak local official, Shanghai Communist Party secretary Jiang Zemin, in a third effort to groom a Communist Party leader who might some day take over the reins of power. Jiang was later given the additional title of chairman of the Central Military Commission, but no one believed he had the political strength to simply step into Deng’s shoes.

By the early 1990s, the broad popular support the Chinese leadership enjoyed in the years soon after Deng came to power had greatly diminished, and Deng’s effort to ensure an orderly political succession lay in ruins.

Times staff writer David Holley was Beijing Bureau chief from 1987 until 1993, when he was replaced by current Bureau Chief Rone Tempest. Also contributing to this report were Michael Parks, now Times managing editor, who was Beijing Bureau chief from 1980 to 1984, and Times staff writer Jim Mann, who was Beijing Bureau chief from 1984 to 1987.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.