With Cloning Success, Ethics Issues Intensify

- Share via

When researchers announced the first successful cloning of an adult mammal, they took a major and, by some reckonings, a troubling step in the science of sex by breaking one of nature’s basic biological taboos, scientists and medical ethicists said Sunday.

The innovation opens the door on to a “Blade Runner” world of human replicants and customized animal clones. Ethics experts said the possibility of creating genetically identical human beings also undercuts an ideal of human diversity on which democracy itself is founded.

But as a matter of practical science, the cloning technique is at least for now too dangerous and ineffective to perform with a human being, scientists said Sunday.

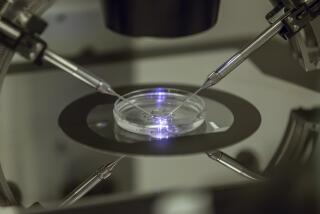

The research at issue was made public Saturday when scientists led by Ian Wilmut at the Roslin Institute in Midlothian, Scotland, announced they had created a healthy lamb from a normal adult cell taken from the udder of a ewe. It was immediately hailed as a groundbreaking experiment--and almost as quickly questioned for its ethical implications.

Even if the technical obstacles can be overcome, the idea of human cloning is so ethically repugnant that society may never allow people to run off multiple, identical copies of themselves on a kind of biological Xerox machine, ethics experts said.

*

A new presidential advisory board on bioethics, meeting today in Washington, is now certain to find the subject of cloning pushed to the top of its agenda, biomedical experts said.

“This is so dangerous and worked so poorly it would be completely immoral to do it in people,” Arthur L. Caplan, director of the bioethics center at the University of Pennsylvania, said Sunday. “Even to try it seems to be outrageously immoral.

“Could someone do this tomorrow morning in a human embryo? Yes. It would not even take too much science. The embryos are out there,” Caplan said.

A code of bioethics adopted earlier this year by most European nations flatly prohibits genetic experiments that would alter future human generations. In consequence, cloning would almost certainly be barred, experts said.

But in the United States, there is no legal obstacle to any researcher who, acting with the consent of the parents who produced a viable embryo, wants to make a human clone, experts said. There may even be medical situations in which human cloning might be desirable, as with families seeking to avoid the risk of transmitting an inherited disease through normal procreation.

“Being able to reproduce yourself would be the most narcissistic act in the world, but there might be circumstances under which it might be thinkable,” said John Fletcher, a noted authority on biomedical ethics at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. “I should not push the condemnation button so quickly.”

While federal funds cannot be used for research involving human embryos, there are so many thousands of “orphaned” human embryos frozen in cold storage at commercial infertility clinics today in the United States and abroad that there would be no shortage of raw material for privately funded human cloning experiments, experts said.

Alexander Capron, a nationally recognized expert on biomedical ethics at USC and a member of the new presidential commission, said that if the technique is simple enough, it may only be a matter of time before “all the many free-standing fertility centers will find themselves called upon by the megalomaniacs of the world to produce for those people the offspring they have always wanted, which is themselves as children.”

In the unregulated world of free-market biology, Capron said, “it will be within the realm of possibility that one of these centers operating with private money will be in a position to apply [cloning] to human beings.”

The idea of constructing perfect genetic copies of an individual has riveted the attention of the research and ethics community, as much as for what it may do to the human self-image as for its inherent scientific merit.

It raises a host of unsettling possibilities, ranging from efforts to breed genetically perfect organ donors to attempts at conceiving children with heightened intelligence or special physical talents. All those possibilities would seem too farfetched to be taken seriously but for the fact that so many people have already tried to accomplish them with less powerful techniques.

“It is going to cut directly across the traditions we have inherited concerning the relations between the sexes and for responsible parenthood,” Fletcher said. “Just the thought of trying to bring up a child who is a biological self-image of another person is a portentous issue.”

“My own prediction is that there will be a kind of moral apprehensiveness and even a deep moral shudder when people think about real cloning,” he said.

But the most immediate effect of the new biotechnology, experts said, will be to transform the relationship between people and the animals they tend.

Cloning offers a means for people to preserve precious pets by copying them, for zoos to revive endangered species by increasing their numbers, and for farmers to tailor genetically engineered dairy herds that can give milk containing, for example, lifesaving pharmaceutical compounds. But it could also narrow the broad genetic pool that makes a species healthy and resilient.

*

The technique, made public Saturday in Scotland by the scientists announcing the birth of the lamb, does not work very well, researchers cautioned. It took almost 300 embryos to yield one healthy animal. Some of the offspring were deformed and died.

“The technique is still extremely inefficient,” said Colin L. Stewart, an embryologist who directs the National Cancer Institute research center in Frederick, Md. He reviewed the new research for the journal Nature, which will publish the technical paper later this week. “This technique as it stands at the moment is of more significance to the agricultural people.”

And although all mammals share the same basic biological machinery of reproduction, there still are enough subtle biochemical differences that scientists often have trouble applying such new techniques for all species.

“No one has been able to get this technique to work in mice,” Stewart said. “It may well be impossible to work in humans.”