At 90, Hans Bethe Shuffles, but He’s Still Slide Rule Sharpshooter

- Share via

ITHACA, N.Y. — In a lifetime spent elucidating nature’s inner workings, physicist Hans A. Bethe has come to rely on a few maxims:

Begin the day with a hot bath. Trust a slide rule over a supercomputer. Tackle only those riddles over which “one has an unfair advantage.”

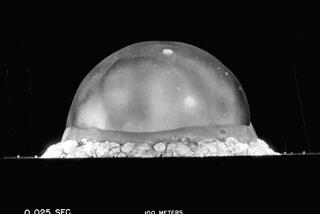

At his zenith, there seemed to be few well-defined conundrums of the cosmos that Bethe couldn’t master, from figuring out how the sun and stars generate energy to his central role in designing the first atomic bomb.

At age 90, the 1967 Nobel Prize laureate thinks his run of scientific breakthroughs--averaging one every decade or so since the golden age of physics between the world wars--has probably ended.

He conceded that recently during a break in his regimen at Cornell University’s Newman Laboratory of Nuclear Studies, where he devotes many solitary afternoons to his passion: numbers.

“I think it’s very useful for keeping me young,” he says, his measured, resonant baritone inflected with a native German accent, his smile mischievous in a face rumpled with age.

The years have sapped a once-sturdy physique. With his mind usually elsewhere, he prefers to shuffle along, fearful that another hard tumble on the ice like one he took last winter could prove disabling.

But Bethe exudes the same indefatigable aura that earned him the nickname “The Battleship” at Los Alamos, the laboratory in New Mexico where the atomic bomb was developed. It begins to explain his renown as one of the 20th century’s most accomplished and admired scientists.

Even today, his work pops up frequently in science journals. In fact, from a total of 300 published research papers, his choice of 20 favorites for a 1997 book collection includes a few recent ones on the collapse of stars.

Bethe turned to astrophysics after his retirement from teaching in 1975. It is a realm he had only dipped into, albeit brilliantly, in a career with myriad parts: scholar, writer, mentor, government advisor, energy prophet and foe of the hydrogen bomb and nuclear arms proliferation.

With his grasp of so many fields of theoretical physics, Bethe was persuaded by a colleague to delve into the macro-mysteries of supernovae, those mighty star explosions that are thought to account for all life in the universe.

“He was 72 when he began, and he was like a kid in a candy factory,” recalls Gerald Brown, a professor of physics at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Astrophysics was just exactly made for him.”

Their collaboration quickly turned heads. A 1979 paper upended long-held assumptions about the density of a collapsing star’s core.

“They all had the collapse stopping at a density about 1,000 times smaller,” Brown says. “I said, ‘Hans, 20 years of supercomputers don’t show this,’ and he said, ‘They’re wrong.’ ”

Bethe cups his hand to illustrate compression inside a dying star. “The buildings of Manhattan would fit into your hand,” he says, his eyes twinkling. “Except your hand is not going to stand it!”

The excitement hasn’t let up. Bethe will spend evenings on the phone with Brown running through their latest theory about low-mass black holes or the antics of ghostlike, high-energy particles called neutrinos--”peculiar animals”--that have almost no interaction with matter.

Astrophysicist John Bahcall of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., says Bethe’s research is still first-rate.

“If I didn’t know his age, I would try to recruit him,” he jokes. “No one has ever found a problem for which Hans did not have an unfair advantage. He could just calculate better than other people.”

Each January takes Bethe to California for a month of brainstorming with old colleagues. Los Alamos, where he served as theoretical division chief of the Manhattan Project in World War II, remains an annual pilgrimage.

Even though the atomic bomb designers knew its calamitous potential, the reality “was worse than we expected,” Bethe reflects. “After Hiroshima, many of us said, ‘Let’s see that it doesn’t happen again.’ ”

Bethe played key roles in the 1963 and 1972 bans on atmospheric nuclear tests and antiballistic missiles. As for a nuclear-free world, he says, “I would quite happily go down to zero, but that won’t happen for a hundred years.”

Rather than flashes of genius, Bethe’s mind selects and combines.

“He sort of sees where the light is at the end of a tunnel and then he just steers toward it rather than bouncing off the walls,” Brown says. “Most people in the field don’t realize they complicate things.

“He has this incredible memory where he always knows something to try when he gets stuck. He doesn’t stay stuck for long.”

That’s what happened in 1938, when leading nuclear physicists were invited to crack a pivotal enigma that had long stumped the best scientific minds: the sun’s energy source.

Bethe came up with his Nobel Prize-winning “carbon cycle” formula six weeks later. He showed that virtually all the energy produced by the most brilliant stars stems from a fusion reaction in which hydrogen serves as the fuel and carbon as the catalyst.

Intense projects such as that were usually thrilling, Bethe says, “but you are mad during that time. I can’t do it anymore.”

Other methods are unchanged, notably his 30-minute bath each morning.

“You sleep and things get somewhat unscrambled in your mind,” he says. “Then, in the bath, I can become conscious of that.”

But, he adds with a chuckle, “Not every day do I find anything interesting.”

Although he cannot program the simplest computer, Bethe has no trouble synthesizing reams of supercomputer readouts. For help, he reaches into his briefcase for a slide rule he’s carried around for 70 years.

Born in Strasbourg, Bethe fled Nazi Germany in 1933 after losing his university post because his mother was Jewish. He arrived in Upstate New York from England two years later.

Bethe emerged in an era bursting with discoveries about the fundamental building blocks of matter. In the infancy of modern atomic theory, he spelled out what was known and unknown in nuclear physics in a classic series of papers dubbed Bethe’s Bible.

Likewise, he investigated the structure of atoms, molecules and solids, devised techniques for calculating the properties of nuclear matter and laid the groundwork for the development of quantum electrodynamics.

“He calculates everything and then correlates it with observed phenomena, and that’s his greatness,” says Sam Schweber, a professor of physics at Brandeis University who is writing a Bethe biography.

“It’s never a general broad theory. It’s always something which comes back to answers that can be experimentally verified or falsified.”

Science has been Bethe’s hunger since boyhood.

“You see, most philosophical questions were quite well answered by the old Greeks, and even better by people from 1500 to 1800,” he says. As for deciphering human character, “I don’t think Shakespeare has ever been surpassed.

“Science is always more unsolved questions, and its great advantage is you can prove something is true or something is false. You can’t do that about human affairs--most human things can be right from one point of view and wrong from another.

“It is the most wonderful feeling when you come to a real answer. This is it, and this is correct! In science, you know you know.”