Stick With the Malaria Medicine

- Share via

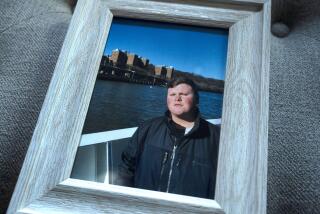

During the first half of his semester in Africa last year, Matthew Nelson took his prescription antimalarial, mefloquine (Lariam) each week on schedule.

But then the 20-year-old Pomona College student noticed some troublesome side effects and blamed them on the medicine. On Sundays, the day he took the medicine, he said he felt depressed. “I was having some stomach problems that I thought might be related,” he said.

Halfway through the school term, he stopped taking mefloquine and felt better.

Other travelers share Nelson’s concerns over side effects from mefloquine, although public health officials consider the drug generally safe and effective.

In Britain, three consumers have taken legal action against Roche Products Ltd., the British manufacturer of Lariam, seeking as yet unspecified damages due to the effects of the medicine. Recently, the trio was given more time to gather data, said a Roche spokeswoman. There are no lawsuits against the manufacturer filed by U.S. consumers “as far as I know,” said Diane Donlon, spokeswoman for Hoffman LaRoche Inc., the U.S. manufacturer in Nutley, N.J. Nor, to her knowledge, have any deaths been attributed to the drug, which went on the U.S. market in 1990.

Despite the legal action overseas, mefloquine is recommended by the federal Centers for Disease Control. “The drug is generally well-tolerated,” said Dr. Hans Lobel, chief of the Malaria Surveillance Unit, division of parasitic diseases at the CDC. He calls it the drug of choice for malaria prevention. The drug has been studied in more than 70,000 subjects, said Lobel, who has conducted some of those studies, “and used by more than 12 million people.” Malaria is spread by the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. It strikes about 500 million people a year worldwide and kills 2.7 million annually. The disease is caused by parasites consisting of single cells, or protozoa, called Plasmodium, of which there are four species. Infections by one of them, P. falciparum, can lead to kidney failure, coma and death.

Combating malaria has been a tough battle. In the 1940s, the disease was eliminated from many temperate zone countries. But then the infection resurged in many tropical regions. Now malaria occurs in more than 90 countries, according to the World Health Organization. Transmission now occurs in large areas of Central and South America, Hispaniola, sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Oceania, according to the CDC. No areas of the U.S. are considered at risk for malaria, according to the CDC.

Lariam became an especially valuable tool as the falciparum parasite developed resistance to chloroquine (Aralen), another antimalarial.

“The risk of getting malaria is greater than the risk of side effects [from Lariam],” said Dr. Victor Kovner, a Studio City internist who focuses on travel medicine and evaluated Nelson upon his return. “Lariam’s bad reputation is very much undeserved.”

Travelers to malaria-stricken areas should start taking mefloquine one to two weeks before departure, Kovner suggested. This will help determine if a traveler can tolerate it well or should switch to another medicine.

During the trip, the mefloquine should be taken once a week for four weeks. Four additional weekly doses are recommended after a traveler’s return.

Among possible side effects listed on the package insert are dizziness, a disturbed sense of balance and psychiatric reactions. Users who notice unexplained anxiety, depression or confusion are advised to discontinue the drug. Other side effects reported included vomiting (3% of users) and dizziness, fainting and premature heart contractions (1%). Others have reported visual disturbances.

About one in 10,000 users has a serious side effect (requiring hospitalization), according to a spokesman for Hoffman LaRoche.

In one of his studies, the CDC’s Lobel compared three antimalarial regimens--mefloquine, chloroquine only and chloroquine and proguanil, another antimalarial--among about 500 Peace Corps volunteers in a half a dozen West African countries from 1989 to 1991.

“Mefloquine was close to 100% effective,” he said, while the other regimens were not. He asked volunteers to complete questionnaires about their symptoms every four months. “From those, it appeared that 30% or 40% of all volunteers complained of something [side effects].”

Researchers at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, working with SmithKline Beecham Biologicals, say an experimental vaccine that protects against malaria and the hepatitis B virus is showing promise. The vaccine was 80% effective in a test on 46 volunteers, according to a report earlier this year in the New England Journal of Medicine. More studies are planned.

For more information on malaria prevention and treatment, call the CDC at (404) 332-4555.

The Healthy Traveler appears the second and fourth week of every month.