Are We Going to a Clean Extreme?

- Share via

BOSTON — People striving to sterilize their homes and hands with anti-bacterial soaps may be fueling the development of dangerous organisms that defy known drugs, according to an authority on drug-resistant strains.

Dr. Stuart Levy of Tufts University, president of the Alliance for Prudent Use of Antibiotics, said last week that the popularity of disinfectant cleaners could not come at a worse time--an era when hospitals are discharging patients earlier to complete their recoveries at home.

He warned that patients may soon be coming home to environments rife with organisms that will resist conventional drugs.

“To me, this is one of the most important new movements afoot that challenges our ability to fight infection,” said Levy, speaking to a conference of science writers sponsored by Massachusetts General Hospital and the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

“My concern is that it’s going to alter the environment, make it worse for the patients who enter the home.”

He said people should use basic soaps to clean their floors, dishes and hands in almost all cases, reserving anti-bacterial cleaners for times when they wish to protect sick family members and those around them.

“Use plain old-fashioned soaps,” Levy said. “They do 90% of what we want them to do.”

Dr. David Hooper, an infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General, agreed that the anti-bacterial soaps are overused. “In the vast majority of circumstances, it’s unnecessary use.”

Levy said he has no evidence that drug-resistant organisms have yet evolved in households as a direct result of antibacterials. But he said it is almost assured, considering the proliferation of drug-resistant bacteria that has stemmed from society’s over-dependence upon antibiotics.

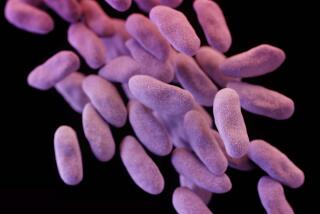

Concerns over antibiotic resistance grew this week amid reports that a tough, new strain of the bacterium staphylococcus aureus had appeared in seven Japanese hospitals.

“Staph aureus” is commonly spread from patient to patient in hospitals, preying especially upon people who have wounds or who are being treated with tubes and catheters. It is one of the most common causes of hospital-acquired infections, which together kill 60,000 to 70,000 people in the United States each year.

The bug has been steadily gaining strength, as the use of antibiotic medications has spawned new strains that are resistant to one or more drugs. The strain identified in Japan is resistant to vancomycin, an antibiotic that is used to fight strains that defy all other medications.

Many doctors are taking a new look at the use of antibiotics to fight such common afflictions as earaches, recognizing that physicians often prescribe them when there is no evidence of a bacterial infection.

But Levy said that antibiotic resistance ought to be fought on two other fronts: in households, where bacterial soaps are needlessly used, and in agriculture, where farmers use them to promote the growth of cattle and to prevent disease in fruits and vegetables.

The drugs are a common component in feeds given to cows, pigs and chickens as well as fish raised in aquaculture. They are also sprayed on fields from crop-dusting airplanes.

Levy said he fears that people will acquire bacterial strains simply by eating foods that have been raised this way.