Birth of a New Islam Coalition

- Share via

WASHINGTON — After two decades of sometimes bloody rivalries, the disparate faces of Islam gather in Tehran this week to address a critical issue: Can they ever reconcile? Could they even develop a common vision? The answer, in the form of a much-anticipated Tehran Declaration, will affect everything from the price of oil in U.S. suburbs to the flash points of the post-Cold War world.

Three kings, seven prime ministers, three crown princes, four vice presidents and 10 other heads of state are among the 55 delegations expected at the 8th Islamic Conference Organization. This summit will differ from all others in the past.

The differences will be visible at two levels: first, among the specific goals of the Tehran Declaration, which are supposed to guide the Islamic bloc until the next summit in the year 2000. Second, in the interaction among countries, for many of the side meetings between delegations may be as telling as summit sessions among them all.

Scattered among some 150 items on the agenda will be repeat subjects such as the Arab-Israeli conflict. Of these, the language is often predictable. But other key agenda items, several proposed by Iran, reflect a significant shift for both host and participants.

In the spirit of the post-Cold War world, for example, one of the defining new issues is neither ideological nor military, but economic. Specifically, Iran seeks to generate movement on an Islamic common market.

The integration of Europe to the west and North America across the ocean, plus the boom years among the Asian bloc to the east, have spawned a basic question: Why are members of the Islamic world not trying the same thing? Islam, they increasingly recognize, will not alone provide. Among several summit observers will be the head of the revived and expanded 10-nation Economic Conference (ECO), which groups Turkey, Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan with six former Soviet republics in the Caspian Sea region of Central Asia, several rich with gas, oil and other resources yet to be fully tapped. ECO is offering a resolution for cooperation and joint development with the Islamic Conference.

The idea of an Islamic common market reflects a strong undercurrent at this summit: confidence-building measures that will bridge the wide religious and political gaps among members. Other resolutions will focus on how to resolve disputes within the Muslim world and territorial integrity of member states.

The tenor differs starkly from earlier times, particularly for the host country. Immediately after its revolution, the Islamic republic government in Tehran felt itself superior to all others in the Islamic bloc. It sought leadership by exhorting others to follow its lead, cultivating opposition within rival states and even imposing its vision. Various sectors of the Islamic world once hoped to recreate the Islamic ummah, or community.

Today, the four-month-old government of President Mohammad Khatami is looking for legitimacy through cooperation among peers. All Islamic bloc members now define their needs, first and foremost, in terms of the modern state, with its distinct borders and regimes.

That does not mean all discussions in Tehran will be amiable or that the outside world will fully welcome the outcome. The West is likely to be the focus of several critical resolutions.

But rather than simply lash out at the West for its woes, the Islamic bloc is also looking at solutions or constructive alternatives. For example, it seeks to form its own news agency and satellite network.

In another break from the past, Iran is even introducing a resolution on Islamic women. “We are recommending that governments pay more attention to the social, political and economic development of women,” said Mohammed Said Namani, an Iranian delegate on the cultural committee. Iran’s new government, which won elections last May partly because of a large female vote, has a woman vice president and 13 female deputy Cabinet ministers.

This kind of agenda reflects a nascent realpolitick within the Islamic world, where passions are now more caught up in qualifying for the World Cup than in religious debate or anti-American rhetoric. Just as telling is the one absence at the summit: Afghanistan’s Taliban, which Iran views as extremist.

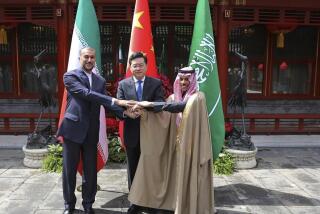

The outcome in Tehran will also be determined by interaction between the two countries that now symbolize opposite poles of the Islamic spectrum: On one end is Saudi Arabia, a comparatively young but rigidly ultraconservative Sunni kingdom that is the self-anointed guardian of Islam’s two holiest sites, Mecca and Medina. On the other end is Iran, a place where one version of revolutionary Shi’ite Islam swept aside more than two millenniums of Persian monarchies and where several other versions now vie for political supremacy. The rivalry between the two neighbors has played out on every critical issue facing the Islamic world.

As alike as they often appear to the outside world, in part because their women wear chadors or veils and their leaders invoke Koranic verses, few Islamic countries are as different, reflected in part by their relationships with the United States. But this week, Saudi Arabia and Iran unofficially mark a detente that has potentially sweeping implications for the Islamic world.

Last week, Saudi King Fahd donated a piece of cloth that covered the Kaaba stone in Mecca’s Grand Mosque, Islam’s holiest shrine, for use at the summit. Embroidered with religious verses in gold, the 330-square-foot cloth will be a backdrop for the Tehran conference, a symbol of the change from the days of confrontations between Iranian pilgrims and Saudi security forces in Mecca.

Over the past year, Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah, the effective ruler since King Fahd’s stroke in late 1995, has hosted the families of top Iranian officials, including former President Hashemi Rafsanjani, for various pilgrimages. Abdullah and Rafsanjani began sorting out some of their countries’ differences while in Islamabad for Pakistan’s 50th-anniversary celebrations. The move toward reconciliation was accelerated by the new Khatami government.

During a visit to Riyadh last month, Iran’s new foreign minister, Kamal Kharazzi, said, “Iran could not force countries in the region to cancel their relations with the United States or to cancel military cooperation with it.” Instead, he said, “An atmosphere of trust must be established in the region so these countries would not see a need to seek help from foreign countries.”

Kharazzi called his visit “a first step toward expanding ties with Saudi Arabia,” then called for joint security arrangements with Iran’s Gulf neighbors.

Longstanding animosity and suspicions will not disappear overnight, between these two countries or in the Islamic bloc. Detente may be all that is achieved short term. But for a bloc of countries that has accounted for some of the most protracted and grisly recent conflicts, such as the civil wars in Afghanistan and Tajikistan, a commitment to real diplomacy is not only welcome. It is long overdue.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.