Hong Kong Sizzles but China Simmers

- Share via

WASHINGTON — For Hong Kong, the Monday hand-over ceremonies meant the end of history, in more ways than one. They marked the effective end of a remarkable age, a half-century from 1947 to 1997 during which the world’s European powers divested themselves of virtually all the colonies they seized in the 19th century.

The hoopla also marked the end of China’s ability to blame history for what happens in the present day. The injustice of Britain’s seizure of Hong Kong in the Opium War more than 150 years ago is now in the past. From now on, Hong Kong is China’s responsibility.

Almost exactly 50 years ago--in August 1947--Britain withdrew from India, its most cherished overseas possession. At the time, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, commemorated the occasion with a renowned bit of eloquence that ushered in the new era of decolonization:

“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom,” Nehru said.

In Hong Kong on Monday night, during Britain’s final retreat from Asia, all of Nehru’s words were being turned upside down. This time, the world did not sleep; the hand-over of Hong Kong was televised around the world. Hong Kong was not awakening to life, because it was already full of life. And as for freedom, that, of course, remains the big question mark.

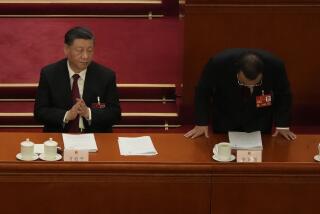

At the hand-over ceremonies, Chinese President Jiang Zemin was unable to summon forth words that will be remembered in the way Nehru’s have been. Jiang’s talent lies in his ability to hold together the Chinese Communist Party leadership, not in his personal dynamism. His stiff body seems to ooze caution out of every pore.

The brief speech Jiang read was wooden, blending together cliches and political jargon with some welcome repetition of the promises China made about Hong Kong’s future in the transition agreement it signed with Britain 13 years ago.

The Hong Kong ceremonies represented, in a sense, the easy part of Jiang’s job. The hard part is back in China, where the Beijing leadership faces decisions about how to reform or close down old state enterprises that are losing more and more money without, in the process, causing massive unemployment and social unrest.

One example: Last March, thousands of Chinese workers in the remote Sichuan Province town of Nanchong staged demonstrations and took hostage the manager of a failing silk factory in order to obtain wages that had been withheld from them.

According to a report on this incident in the Far Eastern Economic Review, “A mob of workers waited at the factory gate. They loaded [the factory manager] onto the back of a flatbed truck and forced him into the painful and demeaning ‘airplane position’--bent at the waist, arms straight out at the sides.”

Eventually, the regime gave in and bought off the workers. It ordered a bank to loan the factory enough money to pay the back wages. The Chinese leadership ordered a media blackout on the incident, so that other workers in other places wouldn’t get the idea to follow Nanchong’s example.

In other words, despite the return of Hong Kong and despite its impressive economic growth of recent years, China still faces many of the same underlying difficulties it has confronted for the past decade: growing gaps in income; widening differences between its booming coastal areas and backward inland regions; failing state enterprises that employ workers who want to keep their pay and benefits.

These are the sorts of problems that cannot be solved by invocations of Chinese nationalism alone. Hong Kong’s patriotic business tycoons no doubt want to help the Chinese leadership with economic revitalization in glitzy parts of China like Shanghai and Beijing, but when it comes to places like Nanchong, they are likely to throw up their hands and stay home.

What happens if China’s economic growth rate dips, so that the country can no longer create enough new jobs for the tens of millions of workers who need them? What happens when, as seems inevitable, Shanghai overbuilds to the point where its markets plummet?

“Of all the politicians in the world, Jiang Zemin faces the most difficulties,” China’s exiled writer Liu Binyan observed recently.

Indeed, all of the talk about how Hong Kong is likely to change China is somewhat misleading.

True, Hong Kong may indeed change some parts of China. It is already the dominant influence on Guangdong Province, the part of China nearest Hong Kong. The Hong Kong spirit of free enterprise and capitalist efficiency also may spread farther than it already has in the cities up and down China’s coastline.

But there are large parts of China too backward, too lacking in infrastructure to even dream of following Hong Kong’s example. Many of the Chinese of Hong Kong are those who had the energy to leave their native country and make lives for themselves. Among the 1.2 billion people they left behind, many are far more resistant to change.

Writer Robert Cottrell once observed that Hong Kong’s remarkable dynamism was created “by Britons liberated from the obligations of Britain and by Chinese liberated from the obligations of China.”

That colonial era is now closed. Hong Kong is now linked, by webs of still not-quite-defined obligations, to China. And for China, history is never over.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.