In India’s Film World, Violence Is Very Real

- Share via

BOMBAY, India — Gulshan Kumar, India’s Cassette King, never had a chance.

The pudgy, pushy captain of the country’s music industry had just finished his prayers in the slum temple he visited every day when three gunmen approached.

“You’ve done enough praying here,” one of them said, according to witnesses. “Now do it up there.”

The men shot Kumar 16 times. He ran, stumbled and died, face down in a urinal.

Bollywood, the world’s most prolific film industry, hasn’t been the same since.

Kumar’s slaying in August, part of a spate of violence involving entertainment figures this year, has spun the industry into a panic. Actors travel with armed escorts. Directors have gone into hiding. Producers are removing their names from the credit lines of films. Studios in Bombay, the movie-making capital, stand empty.

In a nation whose cultural life revolves around movies and music, the headlines have been sensational. The biggest surprise came this fall, when police accused two of the country’s most successful entertainment figures of ordering Kumar’s death. The question now on the minds of many in Bombay: Which big name is next?

“Who’s gunning for Govinda?” screams a newspaper’s billboard in downtown Bombay, referring to one of the country’s best-known actors.

This week’s bombing of a film studio in southern India has spread fear to the heartland. Twenty-three people died in the attack, and though police suspected politics as the motive, the incident showed how dangerous working in movies here has become.

“The industry is under siege,” said Mahesh Bhatt, one of the country’s most respected directors. “We are paralyzed.”

Much of the violence has revealed a long-suspected link between organized crime and India’s world-famous entertainment industry, which churns out more than 700 films a year.

Police and industry insiders say mobsters have long acted as godfathers to India’s movie business, financing producers shunned by the country’s banks. Now, as India’s economic liberalization dries up the mafia’s main sources of income, it is turning on Bollywood’s biggest names.

Organized Crime in Filmmaking Capital

In Bombay, a clamorous city of 12 million people, the mafia has penetrated industry and politics at every level, officials say. It is part of a scourge spreading across the Third World and former Communist countries, where the collapse of state control has left societies vulnerable to transnational gangsters, officials here and abroad say.

“Bombay is now dominated by mafia gangs,” Home Minister Indrajit Gupta said. “They are operating with vast funds of money and are generally using hired killers.”

As a result of Bollywood’s turmoil, the federal government has threatened to intervene if police cannot bring organized crime under control.

The links between the mafia and Bollywood--as the entertainment industry here is known--mirror, in a more dramatic way, Hollywood’s own past ties to organized crime. Numerous writers and investigators have explored the mob’s influence in Hollywood’s studios and unions.

In India, organized crime’s penetration of the industry runs deeper--and it is more violent.

Unlike in Hollywood, where big studios like Paramount and Disney finance most movies, Indian filmmakers have to come up with their own cash. The state-run banks, which for years called the shots in the nation’s state-run economy, never regarded filmmaking as a serious endeavor.

Shut out from legitimate sources, police say, some producers turned to the mob for money.

“It’s an open secret that organized crime has been financing films here for years,” said Charan Singh Azad, former Bombay police commissioner. “For some producers it is their only source of money.”

For the mobsters, backing movies is an easy way to launder money earned from drug trafficking and extortion, police say.

And the mobsters are apparently no less drawn to the glow of stardom than anyone else. Bombay police say Kumar’s killing was planned at the overseas home of one of the country’s biggest gangsters, at a party attended by several film stars.

“The mafia finances films because it makes them look glamorous,” said G.P. Sippy, a longtime film director. “Banks don’t want to finance us because this is a risky business. Most films fail.”

Today, the country’s most respected filmmakers say they don’t have to rely on mob money. But they say they often have to pay interest rates of 36% to 40% on loans from legitimate business people to make their movies.

Producer Is Shot Outside His Office

Bollywood’s string of troubles began in March, when producer Mukesh Duggal, a Bollywood newcomer known for his lively musicals, was getting into his car outside his Bombay office. He was shot 18 times and died before he made it to the hospital.

No one has been charged.

Police say Duggal dealt closely with the heads of the two principal gangs struggling for control of Bombay. Both, police say, are run from outside the country, by Chhota Rajan in Malaysia and Dawood Ibrahim in Pakistan. Neither country maintains an extradition treaty with India.

Bombay Police Commissioner R.S. Sharma said Duggal may have received dirty money to help him break into filmmaking. He probably was killed because he became entangled in a dispute between the two, Sharma said.

“It’s the new chaps who have the mob money,” said Sultan Ahmed, a longtime director. “Duggal was an outsider.”

Neither Ibrahim nor Rajan could be reached for comment.

This year’s violent incidents signal a darkening of the relationship between Bollywood and organized crime.

The recent dismantling of the state-run economy has, police say, removed one of the mafia’s chief sources of income--the smuggling of commodities like gold and consumer goods like electronics. The extraordinary run-up of real estate prices, which in 1995 made Bombay among the most expensive cities in the world, fueled a brief windfall by giving gangs rich opportunities for extortion.

When the real estate boom ebbed, the cash-hungry mob turned to the $750-million-a-year movie business, demanding protection money from figures who in the past veered away from gang ties.

In July, two prominent film directors, Rajiv Rai and Subhash Ghai, were embroiled in such schemes. Rai, who police say refused to take several extortion-related phone calls, narrowly escaped with his life during a shootout with thugs who had allegedly come to his office demanding money. He has fled to London.

When gangs started threatening Ghai, he went to the police. A few weeks later, four armed men were arrested outside his Bombay home. Police say the men admitted that they were on a mission to extort money from Ghai.

The Rai and Ghai cases received little notice until the slaying of the Cassette King.

At 42, Kumar was one of the richest and most influential business people in India. Only 10 years ago, he was peddling fruit juice from a roadside stand. In the last few years, he had become so wealthy that he often boasted that he paid more income tax than anyone else in India--and it was true.

Kumar rose to dominate the Indian film and music industries by an ingenious application of the nation’s copyright law.

Hindi-language films often feature half a dozen song and dance numbers--they have more in common with “West Side Story” than with “The English Patient.”

When a film reaches the screen, its producers typically spin off the music and sell the albums.

What Kumar did was produce cheap remakes of the songs sung in movies. He hired unknown singers and sold the cassettes at a fraction of the price of the originals--about 50 cents each.

Although the traditional film and music companies dragged Kumar into court, they could not stop him. When he died, his company controlled 60% to 70% of the music market.

“Our theory was, music for the masses,” said Mukesh Desai, chief executive of Super Cassette Industries, Kumar’s company.

‘Cassette King’ Slain at Temple

Kumar made a fortune, estimated at more than $130 million. He also made enemies.

In the last days of his life, Kumar told friends that he was being threatened to make extortion payments. He didn’t go to the police.

Despite his rapid rise, Kumar never lost touch with his roots. Not far from his home in the exclusive Lokhandwala compound, he stopped daily to pray at a tiny Hindu temple in a slum called Versova.

That’s where the hit men got him.

“I was brushing my hair, and I thought I heard firecrackers, so I opened the door,” said Paarpru Bai, 48, a mother of four. “There he was, bleeding against my door.”

Kumar crawled a few feet more, into one of the common toilets used by the neighborhood, and died.

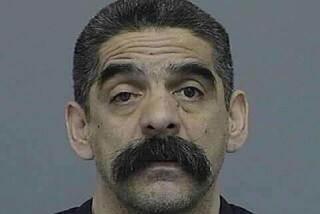

The slaying was followed by even more electrifying news in September and October: Two giants of India’s entertainment industry, Nadeem Saifi, a music director for Indian movies, and Ramesh Taurani, the owner of a rival music company, were charged in Kumar’s murder.

Taurani is free on bail. Saifi could be extradited from London as early as next week. Both men have declared their innocence.

Police say Nadeem, as he is known throughout India, used his connections with Dawood Ibrahim’s gang to have Kumar murdered. The alleged price: $70,000. The exact motives aren’t clear, but police say the killing may have had roots in the men’s estranged professional relationship.

“We have a strong case,” said Sharma, the police commissioner.

In recent weeks, some Bollywood actors have gone into hiding. Others appear in public only with bodyguards.

“I never had any privacy, but I always enjoyed myself,” said Shah Rukh Khan, the Tom Cruise of India, on a break from shooting his latest film. “Now, I can’t even do that. If I walk into a crowd, I’m afraid I’ll be shot.”

Behind Khan stood a guard toting a machine gun.

Bharat Shah, one of the country’s most active movie financiers, said all work on the 25 films he is backing has ceased. And anything that reaches the screen in the near future, he says, won’t have his name in the credits.

“Everybody is scared,” he said.

Authorities say extortion in the movie business is emblematic of the growth of organized crime across the Third World.

People in Bollywood say they look forward to the day their industry returns to normal. Some say it could benefit from a U.S.-style studio system, which might eliminate the need for shady sources of cash.

That’s unlikely without a big infusion of foreign money. And Indian law prohibits foreigners from investing in the movie industry.

More than one Indian filmmaker has said that perhaps it is time the industry opened up like the rest of the economy.

“Coca-Cola is here. Pepsi is here,” said director Prakash Mehra. “Why not Disney?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.