Teen Chlamydia Alarms Experts

- Share via

BALTIMORE — For 11 years, school nurse Marcy Amos has bandaged the skinned knees and treated the asthma attacks of sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders at Harlem Park Middle School. More recently, she and her co-workers have also been grappling with another common problem of adolescence--chlamydia, the country’s most frequently reported sexually transmitted disease.

Sex is nothing new among middle-school kids in this tough west Baltimore neighborhood. Drugs and crime are rampant, family supports are often lacking, and children grow up too fast. As part of her job at the school-based health center, the outspoken and motherly Amos tries to sit down with all of the sixth-grade girls at Harlem Park to give them the facts about sex. She strongly encourages abstinence. But Amos and the other clinic nurses know that in the city’s public schools, the median age of first sexual intercourse is 13 1/2 for girls, 12 1/2 for boys.

For the school’s nurses, asking about sexual activity is a routine part of monitoring students’ health. “I talk about it with everybody,” said nurse practitioner Sharon Hobson, who works with Amos and sees patients in the school health center’s two small examining rooms. “You don’t know unless you ask.”

Pregnancy or a severe gonorrhea infection in the pelvic organs are always among the possibilities that cross these nurses’ minds when a 13-year-old girl comes to the health center with abdominal pain. But in the past few years, they and other health workers who treat sexually active adolescents have begun to worry almost as much about chlamydia, an infection that often causes few or no symptoms in a young woman yet can leave her permanently infertile or can cause premature birth of her infant if she is infected while pregnant.

In the past eight months, a new testing program at the school, being conducted as part of a study by researchers at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, revealed a disturbingly high rate of chlamydia infection among Harlem Park students, most of whom are 11 to 14 years old. Of 135 urine samples taken from sexually active middle schoolers since November, 24--almost 18%--showed infection with chlamydia. Both girls and boys were infected. High rates of infection have also been found in studies of urban high school students in various cities.

The figures reflect an epidemic of chlamydia among teenagers and young adults around the nation--an epidemic that has been smoldering for decades, causing thousands of cases of female infertility, but one that health officials have recognized only in the past 10 years. Nationally, almost 7% of females 15 to 19 years old who were tested at family planning clinics in 1995 were infected with chlamydia, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. For those 20 to 24 years old, the rate was 4%.

“These are young people at the cusp of their reproductive lives,” said James A. MacGregor, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “We’ve got to screen and treat” to detect chlamydia and prevent permanent damage to women’s reproductive organs.

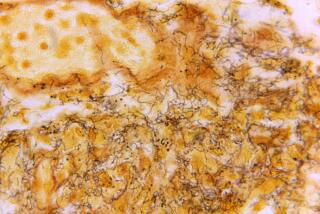

Chlamydia is a bacterial infection that strikes more than 4 million Americans a year and seems preferentially to target the still developing reproductive systems of teenagers and young adults. Researchers say one reason for this vulnerability is that in adolescent females, the tall, columnar cells that form the inner lining of the cervix are also present on the outer portion of the cervix. Chlamydia bacteria easily invade such cells. As women mature, columnar cells on the outer cervix are replaced by flatter cells that are more difficult for the bacteria to infect.

Just how common the disease is in young people has become apparent only since the mid-1980s, as improved diagnostic tests have led to broader screening for chlamydia in family planning clinics and other settings.

The major risk factors are being young--usually younger than 25--and having sex. Although infection rates are higher in poor urban neighborhoods like Harlem Park, the epidemic of chlamydia is not limited to inner cities, said Judith Wasserheit, chief of the division of sexually transmitted disease prevention at the CDC.

“It’s very broadly distributed socioeconomically,” she said.

But there are encouraging signs that the epidemic can be slowed. In those regions of the country that have established vigorous treatment programs for sexually transmitted diseases, chlamydia rates have declined--especially in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, where widespread testing for the disease started in the 1980s.

“Now we can be more aggressive to go after people who don’t come to clinics, or to test people who do come to clinics more often,” said Julius Schachter, a professor of laboratory medicine at UC San Francisco. “Every sexually active individual below age 25 should be tested automatically.”

*

Since 1994, when Congress appropriated money for chlamydia screening, fairly widespread programs to test for the infection in public clinics have been implemented in about 20 states. But government officials and other health experts say not enough is being done, in either the public or the private sectors.

“I think the frustration in the public health community is, here is something that we can screen for, we can treat, we can eliminate, and we are not doing nearly enough screening,” said Barbara Levine, director of government relations for the American Public Health Assn.

Armed with new diagnostic tests that can be performed on a urine sample and an effective, single-dose treatment, health workers in some cities have begun offering testing in schools, shopping malls and juvenile detention centers. The National Institutes of Health is funding research on simpler, cheaper tests that can be used at home.

The goal is to make a national impact on a disease that can render a woman infertile before she reaches her mid-20s, can cause pneumonia, premature birth or eye damage in her newborn, or can lead to a potentially fatal tubal pregnancy.

“In most populations these days, chlamydia is probably the most important cause of tubal-factor infertility”--that is, infertility caused by blockage of a woman’s Fallopian tubes, said Dr. Walter E. Stamm, a professor of medicine at the University of Washington. Scarring or damage to the Fallopian tubes or nearby tissue is estimated to cause about 35% of female infertility, according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Studies suggest chlamydia plays a role in 80% of cases of tubal infertility.

Part of the danger of chlamydia lies in its ability to damage a woman’s reproductive tract while producing only mild symptoms or none at all. The germ that causes the disease, Chlamydia trachomatis, is a species of bacteria that lives and reproduces inside cells.

Schachter and other experts say chlamydia is a major reason for the fivefold increase in U.S. rates of ectopic pregnancy during the past 20 years and for current high rates of female infertility. Many infertile women now in their 30s and 40s probably suffered undiagnosed chlamydia infections when they became sexually active, at a time when the disease was not widely recognized.

“It’s so common,” Schachter said. “Women who either have an ectopic pregnancy or cannot get pregnant--they go in, get evaluated and they’re told they’ve got scarred tubes. They had an infection and they never knew it. That’s chlamydia.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.