Visa Refusal Seen as Effort to ‘Gag’ Defiant Peruvian Editor

- Share via

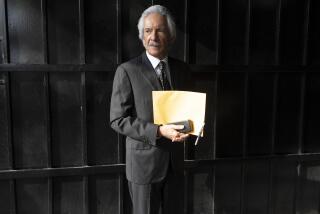

PANAMA CITY — Gustavo Gorriti is the kind of editor who irritates people.

Presidents, cabinet members, even some other journalists find the barrel-chested, gray-bearded Peruvian too aggressive and outspoken.

A year after President Alberto Fujimori forced him out of his own South American nation, he has already worn out his welcome in some quarters of Panama, where he is investigative editor at the venerable daily La Prensa. Authorities here have refused to renew his work visa, citing a long-dormant law that forbids foreigners from working as editors or publishers here.

Known as the “gag law” because of its restrictions on press freedom, the law has not been enforced since Panamanian dictator Gen. Manuel A. Noriega was overthrown by a U.S. invasion in 1989.

The application of the law in Gorriti’s case has worried journalists here because it raises the possibility of other repressive provisions--such as restricting media jobs to journalists “qualified” by a technical panel that would include government officials. “Today it is Gorriti, tomorrow it could be any one of us,” said Arnulfo Barroso, a veteran journalist at the rival Panama American.

Still, Panama’s two main journalistic organizations are divided over the case. The Journalists Union, whose leaders are aligned with the ruling party and the military, has backed the government. The more independent Journalists College--founded to oppose the union and the old military dictatorships--has taken Gorriti’s side.

“Gorriti has made a lot of enemies because he has been a bit arrogant in his treatment of Panamanian colleagues,” Barroso said. “Many people resent this, and for that reason there has been such a marked division about this case.”

Gorriti has received nearly unanimous support from international journalist groups and human rights organizations. The Organization of American States has demanded an explanation from the Panamanian government.

Gorriti was hired by La Prensa, he said, to bring “pep” to the newsroom of a daily founded in 1980 to fight the Omar Torrijos military dictatorship. “They wanted to stress more investigations, complement the dispatch style of news reporting and enhance preparation of the journalists,” he said.

Since arriving in Panama, Gorriti has edited investigative teams that uncovered a drug trafficker’s $50,000 contribution to President Ernesto Perez Balladares’ 1994 presidential campaign, as well as ongoing government nepotism and corruption.

“Labor [and Social Welfare] Minister Mitchell Doens, close advisor to President Perez Balladares, reacted angrily to the media’s investigation into these political scandals, particularly after he himself was named in one of Gorriti’s stories,” according to a letter that the New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists sent to Perez Balladares. “It was Doens who also made the decision not to renew Gorriti’s work visa on Aug. 4.”

After La Prensa appealed Doens’ decision, the government said it had made a mistake by granting Gorriti a work visa last year and cited the gag law.

Just before his visa expired Aug. 29, the journalist sent his wife and two children to the United States and moved from his house into the newspaper offices for safety. Doens called the actions “melodrama.”

Now, it appears that Panama’s courts will decide whether Gorriti will be allowed to stay here.

“For Americans, it might be hard to understand the concept of a journalist challenging laws and defying the state,” Gorriti said. “It goes very much against accepted notions of the rule of law and respect for authority, but . . . in Latin America, we don’t live in systems where there is the rule of law for all. Just for practicing what in other countries would be an ordinary, routine kind of journalism, you can get in major trouble.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.