GM Plans to Spin Off Delphi Car Parts Unit

- Share via

DETROIT — In a move that could improve its competitive position but worsen its already tattered labor relations, General Motors Corp. said Monday that it will divest its huge Delphi auto parts unit next year.

Though not a household name, Delphi would emerge from the complex stock transaction with 200,000 employees and rank as the nation’s 25th-largest company--bigger than Intel, Chase Manhattan or Lockheed Martin.

Delphi, which posted 1997 sales of $31.4 billion, produces AC sparkplugs, radiators and steering components, among much else. The deal is valued by analysts at more than $10 billion.

Although long expected, the deal’s announcement comes only five days after the giant auto maker settled a 54-day labor dispute that erupted in part over GM’s desire to close down inefficient Delphi operations.

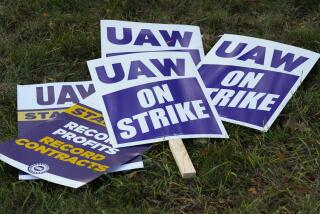

The United Auto Workers union has consistently opposed the Delphi divestiture and late Monday responded sharply to GM’s announcement, saying it would do whatever is necessary to protect the jobs of Delphi hourly employees.

GM Chairman John F. Smith Jr. said the Delphi sale represents a historic, strategic shift away from vertical integration, in which GM produces everything from the smallest part to assembling and delivering a vehicle.

“It is not an advantage today to be vertically integrated,” Smith said at a news conference.

Indeed, Ford Motor Co. and Chrysler Corp. produce far fewer of their own parts, as do many of the nation’s heavy manufacturers. GM is making its move long after the shift away from vertical integration has become a business trend.

Delphi’s roots trace back to GM’s earliest beginnings. GM founder Billy Durant bought AC Spark Plug in 1909 and four years later Dayton Engineering Laboratories (Delco). Soon, he acquired companies owned by Charles Kettering, inventor of the self-starter.

When the company is taken public, it will rank as one of the largest initial stock offerings in U.S. history. Delphi earned $1.2 billion in 1997.

GM plans to offer 15% to 20% of Delphi’s stock in an initial public offering during the first quarter of 1999. Later in the year, the auto maker will divest its remaining holdings by either allowing GM stockholders to exchange GM shares for Delphi shares or grant Delphi shares for GM stock, or a combination of both.

However the deal is ultimately structured, it will be tax-free to shareholders, GM said. It must be approved by federal tax officials.

Most stock analysts praised the Delphi sale. “They are trying to unlock some additional value for shareholders,” said David Healy, analyst with Burnham Securities.

Still, GM’s stock slumped in a down market that hit auto company shares hard. GM shares dropped $1.19, closing at $71.13, in trading on the New York Stock Exchange.

GM makes more of its components than rivals, who can buy the same parts cheaper at outside, often nonunion, suppliers. GM makes about 65% of its own parts, compared with less than 50% at Ford and 30% at Chrysler. (Ford is also expected to spin off its Visteon parts unit soon.)

Standard & Poor’s, the credit-rating service, said the Delphi divestiture could eliminate GM’s competitive disadvantage caused by its high level of vertical integration. But it carries significant financial and labor risks.

“In particular, considerable uncertainty exists regarding the reaction to this move by GM’s principal labor unions,” said S&P; analyst Scott Sprinzen.

UAW President Stephen Yokich said in a statement that the union had long expressed its opposition to a spinoff of Delphi. “That remains our position,” he said.

The union fears that Delphi’s sale will lead to plant closings and possible layoffs. In addition, the parts maker is likely to push in future years for contract concessions, such as lower wages, once it is separated from GM.

“The big concern of the union is a two-tiered wage structure,” said David Cole, executive director of the University of Michigan’s Office for the Study of Automotive Transportation.

GM officials said the Delphi sale had been discussed with the UAW in recent days. UAW employees at Delphi will continue to be covered by the contract with GM and pension and health-care benefits would be unchanged.

The auto maker also said it would honor commitments made last week not to sell Delphi parts plants in Flint, Mich., and Dayton, Ohio, before the end of next year.

A dispute at the Flint plant, as well as a stamping plant in the same city, led to strikes against GM in June. Those plants, however, are not part of Delphi. The walkouts by 9,200 UAW workers cost GM an estimated $3 billion in lost profit and prompted the layoffs of about 190,000 other workers in assembly and parts facilities.

The dispute, settled July 29, left both sides badly battered. In the aftermath of the nasty labor confrontation, analysts were prodding GM to take strong steps to kick-start its stalled restructuring. They argue that GM needs to take drastic steps to improve efficiency, upgrade models and shore up its shrinking market share.

“They need to address the problems of too many of the wrong products, too many divisions and too much capacity,” said Maryann Keller, analyst for Furman Selz in New York.

GM has hinted throughout the labor dispute that it was preparing a reorganization plan that might result in the closing of inefficient plants and elimination of money-losing vehicles.

Ronald Zarrela, GM vice president who heads sales and marketing, is expected today to announce a major restructuring of GM’s North American vehicle divisions.

The initiative and Delphi’s sale are part of a long-running restructuring that began at GM in 1992 when the board of directors forced Robert Stempel out as chairman and chief executive and gave Smith the reins.

At the time, Delphi, then called Automotive Components Group, was a poorly performing conglomeration of disparate plants. J.T. Battenberg was named president and ordered to shape it up.

He instituted a policy under which plants would be either closed or sold if they could not become profitable and competitive. Battenberg ordered that Delphi units become No. 1 or No. 2 in a line of business or they would be sold.

Another goal was increasing Delphi’s international business and non-GM contracts. It has aggressively moved on both fronts. Delphi’s non-GM business has increased from 18% in 1992 to 34% today. Battenberg’s goal is to have non-GM contracts account for 50% of Delphi’s business by the end of 2002.

Delphi’s sale should make it easier for the parts maker to grab more business from Ford, Toyota or other auto makers that now may be reluctant to share technology with a GM-controlled unit.

“Delphi’s independence would substantially help it attract additional business from automotive companies other than GM,” said Battenberg. He also noted that it would have greater access to capital for acquisitions and capital investments.

The parts operation continues to pioneer innovations, and registered 586 patents in the last two years.