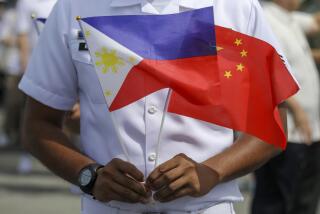

A Faltering Philippines Pact

- Share via

Washington’s security relationship with the Philippines, one of America’s oldest and most important, is in danger of becoming an empty promise unless the country’s legislators decide to retain the joint military exercises that make the U.S.-Phillippines Mutual Defense Treaty a cornerstone of regional stability.

A vote set for October in the Philippine Senate on the Visiting Forces Agreement represents a decisive juncture for U.S.-Philippine relations. Since signing a mutual defense treaty in 1951, Washington has played an indispensable role in maintaining stability in the region. Along with military deployments in Korea and Japan, America’s security relationship with the Philippines remains crucial. The visible presence of military forces engaged in joint exercises and exchanges with the Philippines gives smaller nations in Southeast Asia a sense of security beyond that provided by distant bases in Okinawa or Korea. This sense of security encourages nations to engage in multilateral cooperation and confidence-building measures, instead of seeking strength through destabilizing arms buildups.

America’s level of commitment to the Philippines is interpreted as a sign of Washington’s commitment to the rest of the region; this perception makes joint military exercises more than mere war games.

Joint exercises between the United States and the Philippines have been suspended since 1996, when the Philippine Supreme Court ruled that a permanent, Senate-ratified agreement is necessary before any joint exercises can take place. Although the Visiting Forces Agreement only permits joint exercises, there is fear in the Philippines that the agreement may be a pretext for the return of American bases. Public confusion over the purpose of the agreement and distrust of America complicate Philippine President Joseph Estrada’s defense of even the most limited “return” of American troops.

Washington should move to clear the atmosphere of distrust. Accepting responsibility for the toxic waste left behind at Subic Bay after the closure of the U.S. Navy base in 1992 would be one positive step. Returning two historic church bells would be another. The Balangiga bells, rung in 1901 to signal Filipino guerrillas to attack an American outpost, were taken as war booty after American troops defeated the Filipinos. For Washington, the bells hold no meaning, save perhaps as a minor tourist attraction in southeast Wyoming; for the Philippines, they represent a struggle for independence finally realized in 1946. The good will generated by these two gestures would pay enormous dividends in the upcoming Senate debate.

In a region where what goes unsaid is just as important as what is said, failure to ratify the Visiting Forces Agreement would speak volumes. Since exercises stopped, regional leaders have followed the negotiations over the agreement to gauge American commitment to Southeast Asia. It has become a litmus test for America’s future role in the region. Given the consequences of a perception of American withdrawal from Southeast Asia, Washington must reaffirm its commitment to our oldest regional ally. By working with Estrada to push for ratification of the agreement and by building goodwill between Manila and Washington, the United States can mitigate fears about a dwindling American military presence and send a signal to the world that it hasn’t forgotten its allies.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.