Seeking a Biological Link to Violence

- Share via

Except for the time he was stabbed in the neck, Adrian Raine’s involvement with violent crime has been strictly scientific.

The 44-year-old USC psychologist has scanned the brains of convicted killers in California, noting patterns that might incline them to murderousness.

In Denmark, he and his co-workers showed that babies who endured birth complications and were also rejected by their mothers were more likely than other babies to become violent offenders as young adults.

On the island of Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, his research team has found that the lower a 3-year-old’s resting heart rate, the more likely it is the child will be an unusually aggressive adolescent.

Raine’s far-flung--and to some, farfetched--studies, updated recently in scientific journals, add to his reputation as a pioneer of a new approach to understanding how violent behavior takes hold of some people.

His research is increasingly cited in criminal trials, and although some TV news reports have caricatured it as the search for “natural born killers,” experts have praised his scholarship as being impeccable. The National Institute of Mental Health recently awarded him a research fellowship. “He’s extraordinarily productive,” said Dr. James Breiling of the institute.

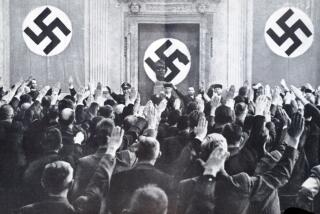

At the same time, some researchers and social critics are extremely wary of probing biology’s role in criminal or violent behavior. That is partly because many nonsensical ideas have been fobbed off as scientific fact, such as the notion last century that thieves, con artists and murderers could be identified by bumps on their heads. Theories of deviant behavior have been used to justify atrocities, from turn-of-the-century U.S. programs to sterilize the “feeble-minded” to Nazi genocide.

A few critics say that such research should not take place at all, because the risk of abuse is so great. Others say that it is not worth the trouble, given that crime is already known to be fostered by poverty, unemployment, lack of education and other social factors.

But Raine and other proponents of the research argue that many vital issues have not yet been addressed. Most people who live in the midst of poverty and unemployment do not commit violent crimes, they say, which only raises the question of what individual factors might spur people with the same background to commit mayhem.

Raine contends that perhaps 15% to 20% of violent criminals were egged on by their body or brain chemistry. Indeed, he is a leading proponent of the view that a biological predisposition to violence is a clinical disorder, with roots in childhood or even the womb.

Among the implications he draws from his work is the notion that a comprehensive approach to preventing violence should include prenatal care and parenting services in poor communities. This would reduce complicated births and improve the mother-child relations that he believes can influence criminal behavior.

More unusual is Raine’s stance on capital punishment: Although he opposes executing convicted killers whose upbringing could have engendered a biological tendency toward violence, he favors executing others whose past lacks such circumstances.

His views on crime and punishment are informed by more than theory. While on vacation in Turkey nine years ago, he awoke in the middle of the night and found a knife-wielding burglar at the foot of the bed. The men wrestled. The altercation left Raine with a 2-inch scar on his neck, a hyper-awareness of noises in the night, and new empathy with the victims of violence.

“I nearly died and I wanted that man to suffer,” he said of the intruder, who was arrested and convicted. “So I can understand when people say, ‘Oh, let’s forget the touchy-feely research on crime.’ ”

One of his most outspoken critics is Evan Balaban, a neurobiologist at the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla. He ridiculed Raine’s studies of murderers’ brain activity as a “Dick Tracy approach to crime,” because the comic strip’s criminals, like Pruneface and Flattop, were so grotesquely obvious.

“I find myself assaulted on all sides,” Raine said.

Others, though, hail the work as groundbreaking. “Adrian’s doing research that is courageous in the sense that he has been criticized for looking at something that is taboo,” said Reid Meloy, an occasional colelaborator and a forensic psychologist associated with UC San Diego.

Raine’s “work highlights some of the ways in which a society might be able to intervene early and effectively in the lives of people who would be predisposed to violent impulsive behavior,” said David Wasserman, a legal scholar at the University of Maryland.

The Effects of Birth Complications

The most important--and most convincing--of Raine’s research efforts, scholars say, is the newly updated study in Denmark.

Run by Raine for a decade, it was originally set up by USC psychologist Sarnoff Mednick to see if birth complications contribute to mental illness. The study involves more than 4,000 boys born at a Copenhagen hospital between 1959 and 1961.

The researchers took note of medically complicated pregnancies and births, including difficult, feet-first deliveries and those requiring forceps. Also, the researchers tried to assess whether each mother shunned her child, as indicated by an abortion request or placement in foster care in the first year.

Decades later, the researchers checked the remarkably thorough Danish criminal registry for the now-grown men. Although only 4% of the subjects had difficult births and suffered maternal rejection, they were responsible for 22% of the crime documented in adulthood.

The long-running study has provided the first evidence that both physical and social stresses may interact to enhance a tendency toward criminal violence many years later, Raine and his coauthors say.

There is no clue how such biosocial stresses might affect the body or brain, and it is far from certain that Danish society, where the murder rate is a fraction of that in the United States, is directly relevant to violence in America.

But Raine proposes a preventive measure: Better prenatal care in the poorest communities. “If we conducted interventions to reduce birth complications or to help make better parents in society, we could reduce some crime and violence.”

To hard-nosed crime fighters, that may sound hopelessly naive. But Raine figures that prenatal care programs and other ambitious interventions could essentially pay for themselves, given estimates that the nation saves at least $1 billion for every 1% drop in violent crime.

Dr. Peter Marzuk, a psychiatrist and associate editor of Archives in General Psychiatry, recently wrote that the work adds to the “growing body of evidence that certain events or situations that occur during critical developmental periods in childhood may predispose some individuals to be violent.”

From Ruffian to Oxford

Growing up in Darlington, England, a town near York, Raine was a slightly built young tough who enjoyed fighting and roaming around with his friends looking for trouble. He got a charge out of throwing lighted matches into mail slots.

What set him on the straight and narrow, he said, was a stable home life. His father, a bricklayer, dropped out of school at the age of 14; his mother sold ice cream from a truck.

“I certainly had antisocial tendencies” as a child, he said. “Maybe if I’d had different parents, less loving and less generous parents, I might have ended up on the same side of the prison bars as the criminals I used to interview in England.”

Instead, Raine went to Oxford and then York University, where he earned a doctorate in psychology. He joined the USC faculty in 1987. In his sparse campus office hang posters for two favorite movies--the fantastically violent “Reservoir Dogs” and “Pulp Fiction.”

Perhaps the most unlikely possible predictor of a violent tendency that Raine and colleagues have uncovered is resting heart rate in children, which they have been studying on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius. It involved testing 1,795 3-year-olds in 1972 and 1973.

When the children were 11, their parents filled out questionnaires assessing temperament and behavior.

Overall, children who had a lower resting heart rate at age 3 were more than twice as likely to be categorized as aggressive at 11, compared to those with higher heart rates. Paradoxical as it sounds, other researchers have found the same thing.

There are two possible ways that heart rate might be related to aggressive behavior, Raine speculates. First, other studies have shown that a low heart rate can reflect fearlessness, a quality that could not only get children into trouble but perhaps blunt the effect of punishment, he says. Second, children with a low heart rate might seek out excitement for stimulation; like well-conditioned athletes, they crave action--”stimulation seeking,” Raine calls it.

Previous studies, including one by Raine in England, have shown that teenagers with lower heart rates were more likely to be aggressive young adults. But other researchers said those studies could not establish a cause and effect. Chronic aggressive behavior might lower heart rates, as does athletic conditioning, they suggested.

The Mauritius research escapes that criticism. It “supports the contention that . . . predispositions toward aggression are occurring very early in life,” Raine and his coauthors wrote in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

Although some researchers say that the link between heart rate and aggression is still too weak to mean much, Raine suggests that children with a low heart rate might be less likely to go wrong if communities provide creative and physical outlets, from piano lessons to soccer practice.

But he has also gone so far as to suggest that children’s resting heart rate should be tested, and that those at the lower end of the scale get special attention--perhaps even biofeedback sessions to coax the heart rate higher--if other factors also point in the direction of aggression or delinquency.

That idea has garnered criticism even from his supporters. “Gee, what are we going to do,” Breiling asked rhetorically, “start changing other people’s heart rates” in order to make them better people?

Whatever its practical payoff, Raine said the Mauritius study provides evidence that research on the biology of violence is not racist. Among the islanders--who are Indians, Africans and Creoles--the researchers found no link between ethnicity or race and low resting heart rate. “These biological factors cut across ethnic and racial groups,” he said. “It doesn’t matter if you’re black or white or Chinese or Indian, the same ground rules apply. At some level that’s a positive thing to know.”

He also addressed the racism charge in his 1993 book, “The Psychopathology of Crime.” To avoid studying whether violence has biological roots, he wrote, would be a “major disservice” to minority groups, which are “disproportionately the victims of violence and crime.”

Brain Scans of Murderers

The brain scans of convicted murderers show the promise--and drawbacks--of using new technology to probe the criminal mind.

The largest ongoing brain imaging study of violent offenders, it appears to be a catalyst for using brain scan technology in the courtroom to shore up the insanity defense.

Conducted with Monte Buchsbaum, a psychiatrist formerly at UC Irvine and now at the Mt. Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, and other researchers, the study included 41 convicted murderers who pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity in either a criminal trial or penalty hearing.

The subjects, who had been found to have mental problems such as schizophrenia or a history of a major head injury, underwent positron emission tomography, or PET scanning. That gauges the activity of brain cells by measuring how much glucose fuel they burn. At the same time, they played a sort of computer game that challenged their short-term memory.

Overall, the study found that the murderers appeared to have less nerve cell activity in certain brain areas, compared with a group of 41 people, some with similar mental problems, who were not murderers. The key difference, Raine said, was in the prefrontal cortex, the bundle of white matter behind the forehead.

Neurologists say this region plays a role in decision-making, and in particular functions as a brake on wild or destructive impulses. A prefrontal cortex that is less active than normal, Raine said, would perhaps give aggressive impulses extra prominence.

“Some people don’t like the idea that violent offenders may have abnormal minds,” Raine said. “But I think what this study demonstrates is that this is simply the case. How we interpret it is open to question and how society makes use of it is open to question.”

One prominent use of the technology has been in the courtroom, to lighten the sentencing of convicted killers. San Diego attorney Christopher Plourd has used PET scans to win life prison terms rather than the death penalty in two murder cases. He told the journal Diagnostic Imaging that PET evidence helped convince juries that his clients had a mental impairment.

Still, neurologists hired by the prosecution have lambasted the technique, saying that no PET scan is able to predict an individual’s behavior.

A major scientific problem with such studies, Balaban said, is that many things could account for the murderers’ slightly different brain scans, other than an ingrained predilection for aggression. For instance, he said, many of them had already been in jail for months or years by the time the scan was done, so it could just as easily be detecting the brain effects of imprisonment.

In a 1996 essay that he said was aimed at Raine and others, Balaban said researchers “who oversell and misrepresent what is still a very incomplete and parochial body of work relating biology to crime and aggression are doing everyone a great disservice.”

Raine is used to the slings and arrows, and acknowledges the shortcomings of the research. Among the brains that have undergone PET scans is his own. It does not show the pattern typical of the murderers he has studied. But it bears some resemblance to that of the serial killer Randy Scott Kraft, sentenced to death in 1989 for 16 murders and accused of many more.

The similarity between the scans is not surprising, Raine said, because serial killers plot their crimes and cover-ups and thus indulge in more complex brain activity than an impulsive murderer.

On one hand, the fact that the PET scan can differentiate an impulsive from a serial murderer seems to validate the technique. On the other, he said, the finding that the scans of a multiple murderer and an esteemed professor (albeit one fascinated by violence) are so similar indicates the technique is still rather primitive.

“A real criticism of the work I do is it’s too simplistic,” he said. “I know that ultimately it’s not that simple. But I have to do this work because there is no [foundation], there is no previous literature.”

Natural Violent Tendencies?

Here are three images from a controversial brain-imaging study of violence by USC psychologist Adrian Raine and other researchers. The sample PET scans show activity in a normal brain, in the brain of a person convicted of a single murder and in the mind of a serial killer.

Normal: Raine points to activity in the prefrontal cortex, the area behind the forehead that neurologists say plays a role in decision-making and functions as a brake on wild or destructive impulses.

Serial Killer: Activity in the prefontal cortex of this person is more similar to that of a normal brain, but Raine says this is not surprising because serial killers generally act with meticulous planning and forethought, not impulsively.

Murderer: The single-instance murderer appears to have less nerve cell activity in the prefrontal cortex. Raine says this could give aggressive impulses extra prominence.