Ethiopia Sees Threat in Resident Eritreans

- Share via

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia — At the Delicious Bakery, a local landmark near this city’s Piazza neighborhood, customers sip tea, munch pastry and slurp milkshake-thick glasses of sweetened avocado juice. But ask for the owner, and you get nothing but nervous glances.

That’s because proprietor Gebre Tensaye was among hundreds of Eritrean businesspeople, government workers and political activists residing in Ethiopia who were rounded up by army soldiers in recent days. They were taken away on fears that they posed a threat to Ethiopia’s security, now that the two intertwined countries in the Horn of Africa have gone to war over their borders.

The detentions, which began late last week, occurred quietly and selectively, setting off panicked rumors among Ethiopia’s large Eritrean community, which Ethiopia estimates officially at 130,000 people but others say could be as high as 550,000. Eritreans, many of whom have lived for decades in Ethiopia, were left to wonder who would be arrested next--and what would be the fate of those detained.

The latter question was partly answered Wednesday when about 800 Eritreans who had been arrested in Ethiopia reached Eritrea after a tough, three-day drive aboard packed buses. The Eritrean government said in a statement Thursday that deportees were forced to make their journey without adequate food or water, before being dumped at Om Hajer, a border crossing near the Sudanese border and 190 miles southwest of Asmara, the Eritrean capital.

“The Ethiopian government continues to pursue its witch hunt of Eritreans with greater intensity,” news agencies quoted the Eritrean government saying from Asmara.

It was unclear whether more deportations from Ethiopia were planned and exactly how many Eritreans have been rounded up.

Plainclothes police chased off two journalists who tried Tuesday to approach an unmarked military camp in the Gulelli district on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, an area where--according to rumors--Eritreans were being taken.

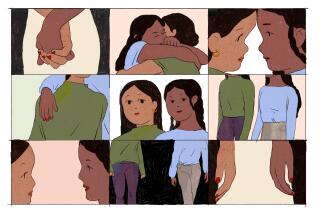

But in the distance, around Quonset hut barracks, could be seen a crowd of people, mostly women and children. They had gathered, evidently, to seek information about their loved ones.

A security guard, asked what was going on, replied only: “These are Eritrean spies.”

But Elias, 24, a restaurateur in the Piazza neighborhood who did not want his last name used, denied that his father was taken because of any political activism.

Soldiers in uniform knocked at the door of the family house at 8 a.m. Saturday, he said, and called for his father by name. “They say, ‘We need to talk to you.’ And then they took him,” Elias recalled. A few hours later, he said, more soldiers came and ransacked their house.

But Elias maintained that his father is innocent of political or other wrongdoing, saying that he and the family believe that Eritreans and Ethiopians “are the same. But the people in Ethiopia imagine things about Eritreans. They only know what the media say, and they hate us now.”

Ethiopia and Eritrea were one country from 1962 until 1993; during most of those years, Eritrean separatists waged guerrilla warfare. But after the Eritrean rebels joined with anti-government forces in Ethiopia to oust the bloody Marxist regime in Addis Ababa in 1991, the two remained close after Eritrea was declared independent two years later.

Many Eritreans continued to reside in Ethiopia, and some even held high, sensitive posts in the civil service, the state telecommunications monopoly and the electric industry. Despite their different passports, Eritreans in Ethiopia enjoyed all privileges of citizenship with two exceptions: They could not vote and could not hold elective office, said Ethiopian parliament member Nefsannet Asfaw.

The rupture in relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea stemming from the border war, which began May 6, has suddenly cast the situation of the Eritreans in a new light.

Ethiopian newspapers, which have painted Eritrea as the aggressor, have carried stories suggesting that Eritrean businesspeople in Ethiopia had secretly raised money for the Eritrean war effort.

The Ethiopian government strongly denies that it is persecuting Eritreans. “The policy of the government toward Eritreans . . . remains intact: They can continue to live and work peacefully in Ethiopia,” said government spokeswoman Selome Tadesse.

But, citing “national security reasons,” she said Ethiopia would oust leaders of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, which has a party office in Addis Ababa; officers of an Eritrean community organization known as C.O.M.; and “individuals who have been raising money for the war . . . and have been involved in spying.”

Because of the fear of sabotage, Eritreans in key government or industrial jobs were to get one month’s paid leave from work, she announced, until their individual cases were investigated. Meanwhile, all Eritreans in the country were ordered to surrender to police any guns that they owned.

Although government officials say the measures being taken are mild and prudent, and essential for national security, the explanations have done little to soothe the anxieties of ordinary Eritreans here.

Elias, speaking in a hushed voice inside the family’s empty Italian restaurant and unsure of his father’s whereabouts, noted that there is pervasive fear in the Eritrean community. “They took so many people,” he said. “I can’t stay. I want to go out of Africa.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.