Exit Polls Suggest Huge OK for Ulster Peace Deal

- Share via

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — In an emotional bid to turn the tide of 30 years of sectarian violence, Protestant and Roman Catholic residents of Northern Ireland streamed to the polls in record numbers Friday and were expected to endorse a power-sharing peace agreement.

Preliminary results from Irish state television exit polls suggested an overwhelming approval of 70%.

All public opinion surveys conducted before the referendum indicated that a majority of voters would approve the watershed Good Friday agreement, despite a large undecided count among Protestants up to the last minute.

Feeling the weight of history on their shoulders, some voters were still debating the pros and cons of the accord on the way to the polls. Others held family meetings Thursday night or gathered in pubs with friends to dissect the deal forged by U.S. mediator George J. Mitchell, Britain, Ireland and eight Northern Ireland political parties, including Sinn Fein, the Irish Republican Army’s political wing.

Still other voters said they knew early on that they would support an accord that offers hope for ending the strife that has taken more than 3,200 lives and for paving the way toward a more stable future in the beleaguered province.

“I don’t care about a united Ireland. I want a united Ulster. I want the two religions to live together,” said Catholic retiree William McCann, 72, in the town of Lurgan.

Eoin Smyth, 25, who works at a McDonald’s in the Protestant town of Portadown, observed: “I’m voting yes. This is the way forward.”

In the final days of the campaign, British Prime Minister Tony Blair, President Clinton and Irish singer Bono of the rock group U2 pitched in to shore up Protestant approval.

A simple majority is required for the agreement to be adopted, but Blair and other supporters said they needed a much more emphatic yes to make the deal work in such a deeply polarized society. Ulster Unionist Party leader David Trimble, who headed the Protestant team negotiating the accord, said he was shooting for a 70% affirmative vote to send a clear message that people on both sides want peaceful change.

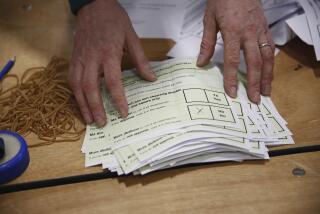

Polling officials said that Friday’s turnout was higher than usual for elections in the province and predicted that as many as 80% of registered voters would cast ballots in the referendum. Official results are due today.

In a parallel referendum, the Irish Republic also was expected to endorse the agreement under which its 1937 constitutional claim to Northern Ireland would be revised to allow residents of the province to decide their own fate.

The 26 counties of the Irish Republic were given independence in 1921 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty that left the six counties of Northern Ireland a part of Britain. The members of Northern Ireland’s Protestant majority think of themselves as British and want to remain under the crown, while most minority Catholics want to reunite with Ireland.

The sides, with the IRA and Protestant paramilitary forces at the fore, have been locked in a 30-year struggle that has become known as “the Troubles.”

The agreement calls for Northern Ireland to remain a part of Britain unless a majority of the residents decides otherwise. At the same time, it turns local government over to the people of Northern Ireland and gives Protestants and Catholics a shared say. An election would be held June 25 for a 108-member Belfast legislature, from which a 12-member executive would be drawn. Important decisions would require both Protestant and Catholic support--a built-in guarantee that one group could not dominate the other.

The deal also would create institutional links to Ireland and Britain. The new assembly and the Dublin-based Irish Parliament would form a North-South council, the first official body to coordinate policies across all of Ireland since the end of British rule in the south. A Council of the Isles would join the governments in Belfast and Dublin, the Irish capital, with London and new legislative assemblies being set up in Scotland and Wales.

While Catholics overwhelmingly supported the agreement, many Protestants rejected it on the grounds that it would give Sinn Fein a role in the new Belfast government and allow early parole for prisoners of paramilitary groups observing a cease-fire. The IRA has maintained a truce since July 1997.

These issues have divided even the leadership of Trimble’s Ulster Unionist Party. Six of its 10 members of the British Parliament are opposed to the accord.

Many Protestants said they moved into the “no” camp after IRA prisoners convicted of murder were furloughed from prison to attend a Sinn Fein congress in Dublin to approve the peace agreement. Among the prisoners there was the four-man Balcombe Street gang, which was responsible for 16 slayings in Britain in the 1970s.

“It’s peace at any price,” said Jim Patterson, 35, a truck driver.

Harry Hamill, 32, a Protestant art professor walking to the polls in Portadown with his two young sons, noted: “You want to vote yes, but there’s some things that stop you, like the prisoners getting out. It’s really hard, honestly. This has divided families.”

Under the accord, political parties are to renounce violence and work for the decommissioning of weapons by their affiliated armed groups. Unionists want the IRA to hand over its guns before Sinn Fein takes any seats in government.

A poll published in Thursday’s Dublin-based Irish Times found that 60% of Northern Ireland voters backed the accord, 25% opposed it and 15% were undecided. Within the Protestant majority, opinion was evenly split, with about a fifth of Protestants undecided.

Blair visited Northern Ireland three times in the run-up to the vote, trying to win over undecided Protestants.

“I understand the concerns that people have about this agreement, and I’ve tried to meet them, but I honestly believe it represents the best chance the future has got in Northern Ireland,” the British prime minister said.

Clinton also appeared on television with Blair in a broadcast from England, asking the people of Northern Ireland “to vote their hopes and not their fears.”

But it may have been the Belfast appearance of singer Bono that helped stem the flow of Protestant votes into the “no” camp. Bono locked hands on stage Tuesday night with Trimble and moderate Irish nationalist John Hume of the Social Democratic and Labor Party and welcomed “two men who have taken a leap of faith out of the past and into the future.”

That image sent a message to voters that this referendum was about political unity more than political prisoners.

To supporters of the agreement, it was also about political maturity.

“I feel it’s time the nation grew up and made adult decisions instead of knee-jerk reactions,” said Pamela Anderson, a Protestant mother of two teenagers who works in the family’s pharmacy in Portadown.

“If we say no, we are saying we don’t want to govern ourselves,” added her husband, Raymond.

Foes said a no vote meant they don’t want the IRA to govern the province. They also said passage of the accord would lead to a united Ireland.

“The Union [with Britain] is safe,” said one opposition poster. “So was the Titanic.”

Fear, distrust and disillusionment fed the opposition. Daryl Gault, an unemployed father of six in Portadown, said his extended family discussed the agreement in his mother’s living room for 1 1/2 hours Thursday night and that all 11 voters decided to cast “no” ballots.

“We all believe it’s not going to work. There have been so many promises and so many letdowns.”

But in Belfast, car dealer Ken Oliver called the accord “a compromise” and said he voted for it even though the IRA blew up his business in 1976 after he had poured “every penny I had” into it.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.