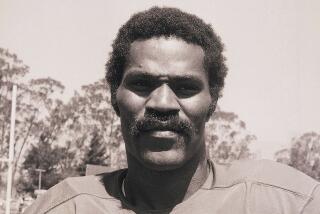

Ben Johnson Trying to Get Lifetime Ban Lifted

- Share via

TORONTO — Even after 10 years, he still would have held the title of fastest man in the world.

And now Ben Johnson is trying reclaim what he says he never should have lost. The muscle-bound blur busted for using steroids at the Seoul Olympics is ready to return to the track at age 36.

“It kind of feels sad to think how fast I could have gone,” he said.

He did go fast, anyway, amazingly fast, blowing past Carl Lewis in the 100 meters for a gold medal and world record of 9.79 at the 1988 Games. Stripped of the medal and the record, he was suspended for two years, and banned for life in 1993 when he again tested positive for steroids.

His second comeback bid rests on a legal battle to overturn that ban by the International Amateur Athletics Federation. He is to appear in Ontario Court on Monday.

Based on assessments from his agent and lawyers, Johnson is optimistic about the outcome, and talks of returning to world-class competition by December or January, perhaps at meets in Australia or South Africa.

He has been training regularly throughout his long exile from track, and estimates he’d need eight weeks of intense work to reach peak form. He says he recently ran 80 meters in 8.14, and believes he could start his comeback with a 100-meter time of around 10.10.

“My dream is to come back again and compete against the best in the world,” he said.

Since his lifetime ban he’s dabbled in real estate and made several public appearances to raise cash and draw attention to his case. He’s traveled to Europe and Japan several times, where the media remain fascinated by him, and last year resorted to such antics as racing against a Toronto radio sportscaster.

Johnson’s agent and manager, Morris Chrobotek, is engaged in a two-pronged offensive to get his client back on the track. He’s collecting documents that he says cast doubt on the 1993 drug test, while focusing the court case on the issue of restraint of trade.

“Let’s say Ben was driving, and maybe he was speeding,” Chrobotek said. “Okay, you take his license away -- but not for the rest of his life. Enough is enough.”

Johnson’s campaign has received little support from anyone at the higher levels of Canadian track and field, whether officials or athletes.

But there seems to be a shift in Canadian media coverage of him, treating him less like a villain and more like someone who became a scapegoat for a widespread problem.

The Canadian Broadcasting Corp. aired a lengthy TV documentary this month that raised the question of whether Johnson was treated fairly. Among those interviewed was Mark McKoy, who came back to win a gold medal at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992 after a two-year suspension.

“I’ve always thought Ben was shafted,” McKoy said. “You get caught, you do your time, you come back.”

Johnson’s quest is followed with interest at the Canadian Center for Ethics in Sport, which helps administer drug testing on behalf of Canada’s sports federations.

The center’s chief executive, Victor Lachance, said Johnson is entitled to his day in court, but suggested the sprinter might have been better off persevering with an appeal to the IAAF.

Lachance said the spate of drug scandals in sports underscores the scope of the problem, but disputed the notion that this should generate sympathy for Johnson.

“There is no question there is doping going on, and no question more needs to be done to ensure we have a level playing field,” Lachance said. “But the fact that other people were not caught doesn’t mean anything unjust was done to Mr. Johnson.”

Canadian sports officials are growing weary of Johnson’s long-running reinstatement campaign and believe the lifetime ban was proper, said Hugh Wilson, director of athlete and coach development for Athletics Canada, the national governing body of the sport.

“People want Ben Johnson to have a good life and make the most of the gifts that he has, but not here in track and field,” he said.

Johnson isn’t alone in his exile. His former coach, Charlie Francis, remains banned from coaching for life, although he appears regularly at major Canadian meets and is sought for technical advice.

Jamie Astaphan, the doctor who admitted administering illegal drugs to Johnson, moved back to his native St. Kitts in the Caribbean. He and Johnson contend that the positive drug test in Seoul resulted from American resentment that Johnson was outrunning Lewis. Johnson, however, also has admitted that he took steroids.

“I beat the Americans--that was the problem,” he said. “If I was American, this never would have happened.”

His bitterness extends to Canada and the United States, and he plans to move abroad, perhaps to Italy, once his reinstatement case is resolved. Europeans, he said, have been more supportive than North Americans, and he never wants to race again for Canada.

He and Chrobotek are planning ways to make money even if they lose the case. They’re about to market a line of Ben Johnson sweatshirts and are trying to stir up interest in a book and movie.

Johnson is convinced he would have proved himself the world’s greatest sprinter had the drug problems not surfaced. He says he could have run the 100 in 9.68. (Fellow Canadian Donovan Bailey holds the world record, 9.84).

“Maybe I’ll get another chance--maybe I won’t,” Johnson said.

He said inner faith, and the support of his mother and sisters has helped sustain his spirits over the years, but he doesn’t feign nonchalance.

“Sometimes I feel depressed--all human beings do,” he said.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.