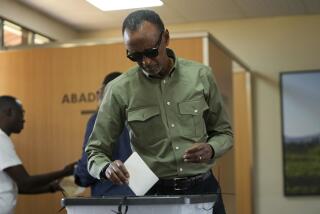

Theogene Rudasingwa

- Share via

Dr. Theogene Rudasingwa is going home. Five years after a genocide that killed more than 800,000 people, Rwanda is calling its best and brightest home to help in the rebuilding. That includes this tall, soft-spoken medical man who has practiced more diplomacy than medicine in his lifetime.

Like many Rwandans, Rudasingwa lived most of his life in refugee camps outside the country of his birth. He was less than a year old when his father, a local chief, was killed in a smaller genocide in 1961 and his newly widowed mother fled Rwanda with her four children. The family lived in refugee camps in Burundi and Tanzania before settling in Uganda. Rudasingwa’s mother worked on banana plantations to pay for her children’s school fees. Her hard work paid off: Rudasingwa became a physician; his brother, Gerald Gahima, just stepped down as Rwanda’s secretary general of the ministry of justice.

In 1990, Rudasingwa volunteered to serve as a field doctor with the rebel Tutsi forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front. But his facility with English became more valuable than his medical expertise. The RPF made him their liaison officer to the outside world, where he tried to detail the Hutu-led government’s human-rights abuses. But Rudasingwa grew increasingly frustrated as his message went unheard: Rwanda wouldn’t register on the world’s radar until 1994.

By then, Rudasingwa had been promoted to secretary general of the RPF. He participated in the historic Arusha Peace Accord, which proposed power sharing with the Tutsi minority. But after a plane carrying the presidents of both Rwanda and Burundi was shot down in April 1994, three months of orchestrated mass killings began. Hutus, urged on by the Interahamwe militia and radio messages of hate, turned against their Tutsi and Twa neighbors, using machetes, bullets and grenades to “cleanse” every town and village of “the others.”

Two years after the slaughter, the new government of Rwanda--the “government of national unity”--again called on Rudasingwa to set aside medicine for diplomacy. For the past three years, he has served as Rwanda’s ambassador to the United States, organizing loans and other financial aid and trying to explain what turned neighbor against neighbor in the bloodiest genocide since World War II.

Rudasingwa arrived in Washington in 1996 with his new bride, Dorothy, a professional with a background in psychology and international development. Today, the Rudasingwa family has grown to include Lisa, 2, and a new baby, Aaron.

This week, Rudasingwa returns home to a country facing enormous challenges. He’ll be bringing his family to a land where there are only 100 doctors for 8 million inhabitants. HIV/AIDS is a particular problem, as is malaria, tuberculosis and measles. There are critical teacher and housing shortages and desperate need for capital investment in an economy built on humanitarian aid. Yet, Rudasingwa, like so many other returning Rwandan refugees, is optimistic about the future.

Question: When I was in Rwanda, I didn’t see the kind of tangible ethnic tensions prevalent in Bosnia, where refugees return to a community to face hostile neighbors and burnt-out homes. Are there tensions under the surface?

Answer: I definitely believe there is some silent tension there which is not obvious to the naked eye. But I should also say the fact that you cannot really see it is a clear indication that, in Rwanda, talking about reconciliation, talking about unity, talking about peace and stability are not farfetched notions. We believe they are achievable goals. Because despite the division that has taken place within our society, still there are certain common grounds that we could emphasize and hopefully, with time, gain some ground on issues of unity, reconciliation, justice and the overall political and economic transformation that we intend to keep on trying to achieve.

Q: But in Rwanda, survivors of the genocide are often living right next door to the alleged perpetrators. How can these people live together?

A: That’s a very, very difficult question in Rwanda today because people who lost their families have been forced by the realities of the time to live with their very tormentors, their very executioners. And this, of course, in a very natural way, creates a sentiment to exact retribution, to exact revenge on those who have committed such crimes against one’s own family. That is the natural inclination that anybody would have. You and me and anybody else would have that kind of inclination. But because the government has been very, very serious about eradicating the culture of impunity, you probably agree with me that we have kept revenge to the very minimum in our own society, even when as I say the natural inclination of anybody would be to exact revenge on whoever committed a crime of that magnitude to one’s family. And it becomes very difficult, therefore, under such circumstances even to talk about reconciliation. . . .

At the personal level, it’s very difficult to forget, it’s very difficult to forgive, it’s very difficult to even understand this whole notion and practice of reconciliation without there being visible motion with regard to justice being seen done in our country. And that’s why we definitely take seriously issues of justice in this country. . . . Other options were tried by previous regimes, and it’s these options that have brought us to where we are today. And so this is the only viable option: to both promote reconciliation and to promote justice.

Q: Is punishment a necessary part of reconciliation? Is it enough to let the truth be told and agreed upon by all sides?

A: That tends to be a controversial subject. There are some of us who believe that for anybody who kills other human beings, that kind of person definitely should face the death sentence. That’s how I look at it. You don’t take away somebody’s life and get away with it.

Of course, there are others, on the other side, who say just taking the life of yet another person does not solve any problem at all. But for me, issues of genocide are very serious, and there has to be adequate punishment to serve as a deterrent to other people never to think about committing that kind of crime again. . . .

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission--the South African version--works in a situation where there have been serious human-rights abuses, but abuses that do not amount to genocide. I think it would be important to note that it may work in certain situations and may not work in other situations. Even in South Africa, it’s too early to see how it’s going to impact society 10 years from now, 15 years from now. It’s too early to say whether, in fact, that is the best form of dealing with that form of situation.

But I believe that telling the truth at the national level, at the community level, is also part of the national healing process. And that’s why we’ve established a commission for national reconciliation within the country. . . . At the national level, also, there has been an exercise for the past several months, meetings chaired by the president, attended by a wide cross-section of people, that have focused on some of these issues that have created problems in our society as part of getting out the truth, so that we can build the future society on the basis of a shared truth.

Q: Recently you called Rwandans and Bosnians “sacrificial lambs” whose deaths weren’t in vain if that’s what it took for the international community to finally take action in Kosovo.

A: I said that if, truly, Rwanda and Bosnia had to go through what we went through in order for the international community--particularly the Western portion of the international community, since that’s really most important with regard to some of these issues--if that’s what it took for them to wake up and say, “These things should not happen in our times, should not happen again,” then probably that was the sacrifice we had to give for people around the world.

Q: In addition to justice, what else is needed to bring about reconciliation in a country torn apart by ethnic strife?

A: There are four other issues that you need to address, the first being the element of political inclusion in our society. Political exclusion and other forms of exclusion in our society were the foundation on which both the idea and the practice of genocide were built. In the case of Rwanda, of course, it was exclusion based on ethnicity. There was exclusion based on region. And there were so many other exclusions that came to be associated with the whole practice of governing in Rwanda. . . . Having some kind of inclusion at the top among the political elite is one thing. I think having political inclusion and a broader participation of the population is another. . . . And that’s why, a few weeks ago, we got involved in these local elections, which is a very historic process.

The second issue that we have to deal with is systemic and endemic poverty. When you go beyond Kigali and more urban centers, you really see the extreme conditions of poverty in our society. Poverty is a condition that denies people broader participation, both in political life and economic life. And it’s a human right, in our opinion. And if you don’t deal with it, you also create a situation where ordinary people, because they are illiterate, they are not active in some of these things, they can easily be manipulated by the elite for certain selfish ends that have nothing in common with the broader interests of the people. . . .

Third, we have to deal with the problem of security. Because insecurity in Rwanda has been so rampant that even taking away somebody’s life was, at one point, taken as something God-given and something you could reconcile yourself to. There are also regional ramifications of security. We have to deal with security within our national borders, but we have to increasingly deal with other partners in the region, to deal with the regional ramifications of this greater problem.

And lastly, the fourth thing we have to deal with is, how do we create a bigger space around us to work with each other through more cooperation and integration, to allow movement of people and goods and services that would somehow create a bigger space around [people], so that we don’t feel we are boxed in this crucible and therefore we have to look at each other as “Hutu” and “Tutsi” and “Twa”?

If you look at the level of literacy . . . , of science, of technology, of managerial skills in our society, of basic technical skills, we are definitely in a very bad situation. . . . People are increasingly talking about the global economy. How can ordinary mothers somewhere in northern Rwanda, barefoot and illiterate, tending to their crops and growing coffee and tea, how do they make any meaningful contribution or get any opportunity from the new global situation?

Q: I met a man who wants to start a farm near the Burundi border, where 90% of the population was slaughtered five years ago. I asked if he was worried something similar might happen again. He told me safety comes when people work together to “protect their bowl.” Does this make sense?

A: Absolutely. They’re [all] protected because it’s their own thing. It’s a way of creating a shared future and a shared interest. But they will also talk to each other. Because when you organize a dialogue around the kind of things that people get involved in, whether it’s a rural health clinic or a school that they’re trying to build, or a joint economic activity of that nature, then people begin to talk to each other. And when they talk to each other, some of the barriers that they may have toward each other consequently begin to crumble. This is an experience that has been shown to work not only in Africa, but also other parts of the world. When you organize dialogue or contact around some of these joint efforts, then it becomes possible for people to talk to each other and it becomes one way to break down barriers.

Honestly speaking, if in Rwanda we are not able to create this economic space around people, if we cannot create more economic opportunity, then that reconciliation and justice are going to be extremely difficult to achieve.

Q: What lesson can Rwanda teach Yugoslavia about resolving conflict and living together after such horrible ethnic violence?

A: The one very, very important lesson that Rwanda can teach to the world is that it’s within the capacity of the people, it’s within the capacity of a population, to do certain things for themselves. Because in our case, whether it was in stopping genocide, it was the Rwandan people who were able to do that--despite the fact that the rest of the international community had abandoned Rwanda and the Rwandese people. We did it on our own.

When it came to post-genocide reconstruction and reconciliation, again it’s the ideas of the people and the practice of the people that was very crucial in the whole equation of trying to put people’s lives together and charting the course ahead. There can never be a substitute for the ideas of a people and for the practice of a people. Being able to do things for yourself is a very important element in moving ahead.*

“It’s very difficult to forget, it’s very difficult to forgive, it’s very difficult to even understand this whole notion and practice of reconciliation.”

“Political exclusion and other forms of exclusion in our society were the foundation of which both the idea and the practice of genocide were built.”

“Rwanda can teach to the world (that) it’s within the capacity of the people, it’s within the capacitiy of a population, to do certain things for themselves.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.