A Pair of Cultures Finds the Future Lies in Reform

- Share via

At a time when the headlines out of Asia are about threats of war or economic travails, two widely separated Chinese cultures are openly concerned with asking the right long-term questions. First, China itself, as exemplified in a little-noticed speech in Houston last month. Before an audience of U.S. energy company tycoons whose investments in China reflect a major interest in that country’s stability, top energy official Xu Dingming stated flatly that China would never turn its back on internal reform. Xu is obviously a Communist from the gene pool of the late Deng Xiaoping, who famously told the Chinese that it made little difference whether the cat was black or white, so long as it caught the mouse. Xu declared that China was irrevocably moving from a planned to a market economy. (Interestingly, the word “communist” never appears in his address.) Globalization, he suggested, is an unavoidable force: “Opening to the outside is a long-term basic policy of China which it will firmly continue to carry out.”

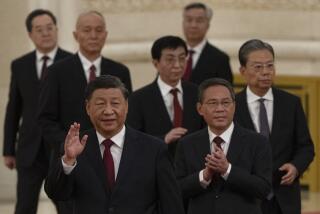

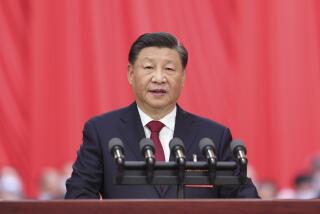

Xu spoke only weeks after the embarrassing and tragic U.S. bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade and just after the jarring “state-to-state” declaration of Lee Teng-hui, Taiwan’s leader. Notwithstanding that uproar, Xu’s comments suggest that the Chinese determination to forge ahead is so deeply embedded in its official thinking that almost nothing can knock it off course. Xu claimed that President Jiang Zemin and Premier Zhu Rongji realize that “deep reform,” including China’s vital energy industries, is driving the economy. That reform must also, Xu claimed, lead to much better environmental policies. In fact, nine of the world’s 10 most polluted cities are in China, where the leading cause of death is respiratory illness. Xu agreed that China’s government is, like every other government, morally responsible “for the condition of the global environment and the air pollution issues with which humankind is faced.”

Beijing does not ordinarily permit top officials to deviate from the official line. So if this is the true official Beijing view, there is yet hope for troubled China, not to mention Asia’s polluted environment.

Now to the other Chinese culture, Singapore, whose people are also enmeshed in a significant rethinking of their ways. For as successful as they have been--this tiny city-state boasts what is probably Asia’s highest standard of living--there is growing doubt there that the old ways can do the trick in the future. Reflecting this, Senior Minister Lee Kuan Yew in a speech this month argued that the former British colony must open its doors to the outside more widely. He praised economic rival Hong Kong for its continuing ability--the handover to Beijing notwithstanding--to attract the best and brightest Chinese talent from southern China; he praised Shanghai’s leaders for attracting talent from all along the giant Yangtze Delta. Singapore, with a miniscule home-grown labor pool of not more than 3 million, wants to attract talent from all over, too. But this buttoned-up society is going to have to loosen up if it wants to shed its reputation for being the sternest, stuffiest place this side of an upmarket reform school. In fact, this view, rarely aired inside Singapore, was the recent focus of an editorial in Singapore’s Business Times. “There is no question that Singapore has to open up if it wants to be more global and cosmopolitan,” said the respected economics and business newspaper. Today’s modern, well-educated and affluent Singaporeans, it suggests, are no longer willing to let anyone--even Lee Kuan Yew--do all their thinking for them.

It’s not always clear from the crisis-oriented news about Asia that such self-examination is occurring in two distinct Chinese societies. But this shift is a good thing. For in the process of identifying their core problems, China and Singapore, though different in size and economic accomplishment, will inevitably run up against a deeper issue: Whether their political systems are open and robust enough to generate the kind of societal consensus needed to implement the policy solutions they require for success. Stay tuned.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.