Family Ties ALS Patient to Illness--and Healing

- Share via

DANVILLE, Vt. — The first hint of trouble came last summer, when Curtis Vance started losing strength in his legs.

Homer Fitts recalls the September day when he and Curtis helped a neighbor harvest his corn. Curtis was driving the truck. “His legs were getting weak,” says Fitts, 72. “Someone else had to get out to open the gate because he couldn’t get up.”

Curtis had noticed the weakness a month before, when he struggled to carry building materials up a step. Maybe it was too much sun, or too much work. He was putting in 12-hour days at his job at IBM and working construction with his friend Jon Webster on weekends. Or maybe it was the pork he’d eaten at a barbecue.

As summer passed into fall, Curtis grew weaker. He visited doctors and they, too, thought it might be trichinosis from the pork. But they weren’t sure, and they sent him to other doctors.

“Every day was a little bit worse,” Curtis says. “The next thing you know, you’re walking funny, you’re walking with a cane. It’s scary.”

The 25-year-old man started using a walker. By November he was going to bed at 7 p.m. and sleeping right through the night. In December he learned what was wrong, and it wasn’t fatigue or bad pork.

It was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis--ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

“It’s like a death sentence,” says Heidi Erdmann, Curtis’ 24-year-old girlfriend. ALS kills, and before it kills it weakens and paralyzes.

To some, this would seem to be the end of the story. But for Curtis and Heidi, this diagnosis was the start of an odyssey of the heart.

It has taken them into spiritual realms. Each week friends and family gather for healing circles, trying to achieve with faith what science cannot do. Strangely, unexpectedly, it has enriched their lives. And it has helped them understand how this disease has cursed his family for generations.

For 10% of those who contract the disease, the cause is genetic. For reasons unknown, anyone with the gene can expect to get it sometime in his life, says Diane McKenna-Yasek, an ALS research coordinator at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Curtis’ mother, Linda Vance, had heard of a family disease, but she didn’t know what it was or the likelihood that she carried it. Her mother died in the 1960s, at 39, of a fast-moving disease then called progressive bulbar palsy. Linda’s sister died of something then called spinal muscular atrophy.

All of these diseases are one and the same: ALS.

It was ALS, Linda Vance knew, that killed Samuel Farr, her great-great-great-grandfather, in 1865, two years after he fell ill. He was 42.

“My whole life has been under this black cloud . . . because of this,” says Linda.

After Curtis was diagnosed, the family called Mass General and discovered that McKenna-Yasek was already well acquainted with their family curse.

The hospital had a thick sheaf of documentation on the generations that had left the Danville area. They learned Farr’s brother and sister had also died of ALS, at ages 40 and 54. Of Farr’s eight children, four died of ALS--one daughter at age 27, says Heidi.

“It’s a fairly incredible family as far as the history goes,” says McKenna-Yasek. “This family Farr was actually recorded in the medical journals in the 1800s.”

The roll of the dead is impressive and depressing; it gave Curtis no reason to hope. The winter was hard. As Curtis’ condition deteriorated, doctors put a pump into his spine to administer an experimental medication. He was flat on his back for weeks, and the surgery left him with blinding headaches.

Heidi cried a lot. “At the beginning, it was all doom and gloom,” she says. “First we were faced with the unknown. Then we found out it was this incurable disease. That was total helplessness.”

But Curtis wouldn’t let her sit around feeling sad. “He always says, ‘Whatever it is, we’re going to deal with it. I’m going to be better.’ He needed me to stay strong.”

She and Curtis met as teenagers when she visited her grandparents each summer in Danville; he was a standout high school athlete, she a competitive tennis player. As athletes, they know the power of a crowd’s energy when it’s focused on one point, or one person.

“Yes, it’s incurable. But we can go past that,” says Heidi. “We’ve really learned how to surround ourselves with positive people.”

And that is how the healing circles began.

Each week, neighbors crowd the side table with banana bread and brownies and stand around in the living room swapping greetings and anecdotes. Many remember Curtis as a newborn; they often speak of his mother’s pride. Some have been in Danville so long they remember Curtis’ parents as children. Old friends joke with his father, who served in the Vermont Legislature for 10 years.

Vance sits in a recliner, chatting.

Each circle lasts an hour. A facilitator, Diane Webster, leads two dozen participants through breathing exercises. She tells them to send positive energy toward Curtis, to touch him to direct the energy through their hands. She asks them to think of Curtis and Heidi in positive, happy, healthy times.

Some people at the circle wholeheartedly believe in energy healing and have done it before. Others are deeply skeptical but want to help any way they can. And all say it helps them to visit Curtis and Heidi and to show their love and support.

“This disease just makes me feel powerless, absolutely powerless. This is one way of getting some kind of power,” says Jenness Ide.

Curtis’ mother cries a lot at the sessions. She believes in miracles.

“I don’t think we have any other choice,” she says. “There is no hope otherwise. If this doesn’t turn around, it gives no hope for anybody else in the family, and we have a very extended family.”

Heidi believes too. She thinks “any disease originates from both outside forces and from within. Yes, you can have a genetic mutation so you’re more inclined to get ALS, but there’s a reason for getting it; there’s a reason that Curt at age 25 got it, and not his four brothers and his mother.

“Curt and I believe it’s a reason that’s above us, it’s unexplainable, it’s a spiritual reason. There’s a point; Curt was meant to do something.”

The disease has progressed. At night, a machine helps Curtis breathe. He gets around in an electric wheelchair he calls his “big rig.”

Still, in some ways, ALS has liberated Curtis.

Now that he’s not working as many hours as he can to earn as much money as possible, he has time to spend with Heidi--reading, talking or just hanging out. Their relationship has blossomed in a way that would have been impossible before he was forced to slow down.

“We’ve become so spiritually in tune that I feel very often that we’re one,” Heidi says.

Curtis has been working with a Brattleboro doctor who is helping him think about, and talk about, what the disease means to his life. He’s meditating a lot, something he never did before.

“There are a lot of different ways of approaching this,” he says. “It’s not that bad. I could have gotten hit by a car, but here I’ve got all this time. And like I always say, who knows?”

Curtis still wishes they could go back to the initial diagnosis of trichinosis. “Wouldn’t that be great?” he says.

But mostly, he dwells in the present.

Homer Fitts has adapted his dock and his boat so Curtis can get out on Joe’s Pond with him to fish, and he’s looking forward to that. Curtis jokes with his parents, complains about the way the local news covers high school basketball. And for the first time, he notices the beauty of the rural town where he grew up.

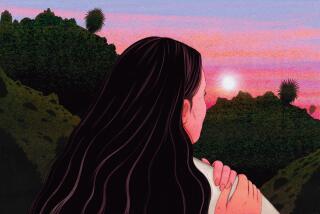

“We’ve got these beautiful mountains,” he says. “I’ve lived here my whole life, and I saw them, but I really never noticed them and their beauty. Now I do all the time.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.