News in China Has 2 Tiers--for Insiders and the Hoi Polloi

- Share via

BEIJING — Top Chinese media reported President Clinton’s apologies for NATO’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia within hours of the May 8 attack. But average Chinese readers couldn’t see the reports.

Why? Because they were published in China’s vast and secretive internal press, available only to officials.

China’s state-run press contains two channels. One is the regime’s “mouthpiece” for conveying directives and propaganda to the masses, and the other is its “eyes and ears,” which funnels intelligence to the leadership.

The system is an enduring feature of centuries of autocratic rule. In times past, the emperor got his news from handwritten memorandums sent to him by provincial officials. With brush and vermilion ink, the Son of Heaven would write in the margins his instructions for how to handle the event reported. He would then return the memorandum to the sender or dispatch it to the appropriate bureaucratic department.

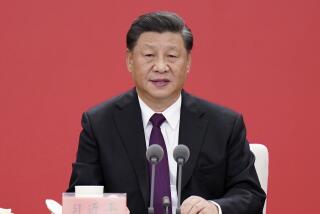

Today, sources say, President Jiang Zemin, Premier Zhu Rongji and other officials read confidential reports handwritten or typed by reporters of the official New China News Agency and major newspapers. The top “comrades” then write their instructions in red ink on the reports and pass them on to the bureaucracy for processing.

The internal news system includes translations of foreign media reports as well as foreign and domestic reporting by New China News Agency staffers. Every party paper has an internal edition.

Critics point out that the ultimate result of giving the New China News Agency a monopoly on foreign news is copyright violation on a massive scale. Based on a set of vague, decades-old exchange agreements it has with Reuters, the Associated Press and other outfits, the agency pays for none of the foreign media reports it reprints.

Now the internal system is being weakened. As the government reduces its funding for the official press, domestic reporters are increasingly writing for more commercially viable news outlets.

And since Chinese newspapers began going online in the past five years, young, tech-savvy reporters have become adept at culling foreign news from the Internet, doing an end run around the New China News Agency and increasing the volume and sophistication of international news in the Chinese media.

According to a twentysomething reporter at a popular weekly newsmagazine, “nobody talks about it, [but] everyone does it.”

Reference News, a watered-down public version of the internal press, sells briskly at kiosks across China and boasts a circulation of almost 3 million copies daily. Known to Chinese as “little reference,” it is popular because it is the only paper composed entirely of foreign media reports--although reports critical of China are censored.

For top officials, the huge international news-gathering division of the New China News Agency compiles “big reference.” This unwieldy volume has more than 100 pages with news about China’s diplomacy with foreign countries, foreign reporting on China and major news from around the world. It is also condensed into three or four pages.

“The policymaking apparatus relies mainly on this thing to understand what’s happening in the world,” says professor Wu Guoguang, a former People’s Daily editor now teaching at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “They can’t read foreign languages, and they can’t receive foreign broadcasts.”

Restricting news about public affairs to internal reports, says Zhao Yuezhi, an expert on the Chinese media at UC San Diego, “means that citizens are systematically excluded from vital information. . . . There is no notion of the public’s right to know in the practice of an internal press.”

But with the growth of investigative journalism and the tabloid press, Chinese reporters now have a choice.

By secretly reporting sensitive issues to high officials, they can prod the government to resolve those issues quietly while scoring official recognition for themselves. Or, if that doesn’t work, they can report an issue to their readers, putting public pressure on the government to solve the problem while winning readers with their exposes. Increasingly, they choose the latter.

“Some comrades think that unless they name names, expose faults, cause a furor and create pressure through public opinion, they’re not watchdogs,” the journalism magazine News Battlefront griped.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.