Invisible Women

- Share via

Michelle DuPont sat down in her new primary care doctor’s office and was immediately put at ease by medical forms that listed “domestic partner” as a choice for marital status. She filled in the name of her partner of three years, Lisa, and thought to herself how pleasantly progressive the doctor seemed.

When Dr. Ronald Axtell asked her if she used birth control, DuPont says she responded, no, “I’m lesbian and therefore pregnancy isn’t an issue.”

After finishing a pelvic exam, Axtell suggested she make her next appointment with one of two other doctors in his Mission Viejo medical group. DuPont, 39, assumed he was sending her to a specialist for something he found during the examination.

Then, says DuPont, the “bombshell” hit. The doctor told her he didn’t approve of her gay “lifestyle.”

Still on the examining table, in a flimsy paper gown and feeling vulnerable because she’d revealed her need for antidepressants in the aftermath of childhood sexual abuse, she felt humiliated.

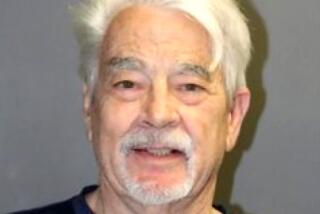

Axtell doesn’t dispute offering opinions about DuPont’s sexuality and referring her elsewhere during that June 1998 visit, says L.A. attorney Jeff Moffat, who represents the doctor in a discrimination lawsuit the American Civil Liberties Union filed on DuPont’s behalf in state court May 13.

Moffat denies that Axtell discriminated against DuPont, saying the doctor did not refuse to treat her and made other arrangements for her to receive care.

DuPont, who now lives in the Oceanside area, has been openly gay since age 27 and her sexuality never before posed an issue, including with the Capistrano School District, where she formerly worked as a teaching assistant.

“I’m not Pollyanna, but I never would expect it from a doctor,” says DuPont. But the impact of the event is that she waited nearly a year before seeking treatment for the anemia that brought her to Axtell in the first place.

DuPont’s story illuminates a topic that is gaining attention: the health of gay women, long overlooked by medicine. Among the questions researchers are posing is whether lesbian health is suffering because of self-imposed exile from the doctor’s office.

Like their heterosexual sisters, lesbians fear sexism in the examining room. But many also approach a medical appointment with the emotional baggage of experiences with judgmental, ignorant or homophobic doctors, experts in the field say.

Report Drew Attention

to Lesbian Health

In January, the Institute of Medicine, part of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, released its first report on lesbian health, commissioned by the National Institutes of Health and the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That document began pinpointing research and knowledge gaps.

“When the Institute of Medicine makes a recommendation or comes out with a report like this, generally the scientific community follows it,” said Suzanne G. Haynes, assistant science director at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Office on Women’s Health, whose agency is planning a follow-up workshop next year.

From Seattle to Boston, researchers are looking at attitudes and behavior that keep lesbians out of the health care system or invisible inside it. They’re examining rates of Pap smears and mammograms and revisiting societal assumptions that lesbians drink and smoke heavily. Others are probing risks for breast and reproductive cancers, which may differ from those of heterosexual women because lesbians tend to skip or delay childbearing. Others are focusing on sexually transmitted diseases, including the rare woman-to-woman spread of HIV.

The Gay and Lesbian Medical Assn. is asking the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics to include questions about sexual orientation in the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, which is used to formulate health policy.

Basic questions about lesbian health can’t be answered “unless the question about sexual orientation gets included in these surveys,” Haynes said.

Like women who lobbied for inclusion in clinical studies that traditionally excluded them, gay women banded together to raise their profile as a study population. The San Francisco-based Lesbian Health Fund provides start-up grants to researchers who can later apply for federal funding.

Addressing lesbians’ health requires dropping preconceptions. For example, some doctors and lesbians mistakenly assume women not having intercourse with men aren’t exposed to viruses responsible for many cervical cancers, although the truth is they can be passed by men and women. Ask Bettye Travis, 47, of Berkeley, who was 40 when she was diagnosed with cervical cancer: “It had been 20 years since I had been with a man.”

Doctor, Patient Must

Be Able to Communicate

Candor between doctor and patient is crucial. Given results of several limited studies of lesbians in which anywhere from 75% to 90% said they had been sexually active with men in the past--and a smaller percentage acknowledged recent sex with men--those who fail to reveal such activity may miss critical screening and attention.

Good care requires diligence from patients, too. Dr. Jocelyn White, co-editor of the Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Assn., will present data at a health forum later this month about lesbians in Oregon who have established good relationships with straight doctors.

“Hopefully that kind of information can be used by other lesbians to influence the way they find and meet new doctors,” White says.

Dr. Marki Knox, an obstetrician-gynecologist who works part time at the L.A. Gay and Lesbian Center’s Lambda Medical Group, says she’s examined many lesbians who reported going years without seeing a doctor. One woman said she had let 17 years pass.

What Happens When

Treatment Is Delayed

Sometimes the consequence is uterine fibroid tumors that grew. Knox treated two patients whose premalignant lesions were probably present about five years.

Knox says some women complain about having visited doctors who insisted they couldn’t be lesbian “because they were too attractive or appeared too normal.”

“I’ve had physicians tell them the problem was they had never had a normal sexual relationship and if they had, they obviously would be cured,” Knox says. “These were in California. We’re not talking Appalachia here.”

With changes in health care coverage and plans providing new members with just a printed provider directory, “you’re picking somebody randomly out of that book and you don’t know if that person is a homophobe or not,” says Kim I. Mills, education director for the Human Rights Campaign in Washington, D.C.

Some lesbians venture to a new medical office seeking signs the doctor will be “lesbian-friendly.” They pray not to be asked repeatedly why they aren’t using birth control if they’re sexually active. Some would rather go home with unneeded birth control pills than “out” themselves to a stranger.

A 43-year-old animator from North Hollywood who asked only to be identified as “Nancy” recalled a visit to an older ob-gyn in Burbank. He told her some medical professionals consider homosexuality to be a form of mental illness. Her frustrated retort: “These are the things that make teenagers commit suicide when they’re confused about their sexuality.”

Suzanne Newman, a 34-year-old video producer-director from New York City, recalled telling a new doctor that she was a lesbian. He performed a painful pelvic exam. When she winced, he said: “What’s the matter, missy, you can’t take it?” Newman then paid out-of-pocket to see her former doctor.

Knox says doctors must be aware of sexual behavior to assess risk for STDs. At Lambda, patients fill out questionnaires asking if they’ve ever been sexually active with men and how many partners they’ve had in the last year.

Knox says people assume that men sow their wild oats but women don’t; that “if a woman is a lesbian, she’s going to ‘get married’ and stay with that woman.”

“If you don’t acknowledge somebody as a lesbian, you aren’t going to ask any questions about . . . high-risk behavior,” Knox says. Doctors believe it’s hard to transmit gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis and HIV from woman to woman but easy to spread herpes and the human papillomavirus that causes genital warts.

Kathleen A. Ethier, a Yale University behavioral scientist, received the first CDC grant to study lesbian transmission of HIV. She has just begun collecting data in New York, Baltimore, San Francisco and Washington.

Ethier hopes to not only identify cases of female-to-female transmission of HIV, but also gather information about behavior “because there are no prevention guidelines for women who have sex with women.”

Dr. Patricia Robertson, a member of the Lesbian Health Fund advisory committee and an ob-gyn at UC San Francisco, says researchers need to know whether HIV can penetrate protective barriers women use during sex, such as latex squares called dental dams. She’s concerned that when lesbians venture outside same-sex relationships, they’re more likely to have sex with bisexual male friends at high risk and then put their lovers at risk. She worries about women who shared needles while injecting illegal drugs, passing HIV to female partners.

Besides federal research, there’s work at the state level, too. Dr. Mhel Cavanaugh-Lynch, director of the California Breast Cancer Research program, based at the University of California system headquarters in Oakland, has funded research into lesbians’ risk of breast cancer. Some of the early findings have been surprising. For example, lesbians reported having more breast biopsies but no higher rates of malignancies, which hasn’t yet been explained.

Elisabeth P. Gruskin, a research associate with Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, has gathered some of the first data on lesbians’ use of services within an HMO. Working from a 1996 survey of 36,000 of Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California members, she and her colleagues studied nearly 10,000 responses from women, comparing lesbian and bisexual women with straight women.

She was intrigued to find lesbian and bisexual women equally likely as heterosexual women to use preventive health care and more likely to rely on alternative medicine like chiropractic care and acupuncture, which might explain where some gay women seek medical care when they’re not seeing MDs.

A Comparison of

Gay and Straight Women

Gruskin found younger lesbian and bisexual women drank and smoked more than straight women, but differences disappeared among those older than 50.

“The moral of the story is . . . younger women seem to be at higher risk,” she says.

Gay and bisexual women were likelier to report having had or been treated for severe depression; they were marginally more likely to report taking antidepressants.

As attention to lesbian health increases, the ACLU hopes DuPont’s case, the first case of sexual discrimination in a doctor’s office brought under the California Civil Rights Act, will draw more attention to treatment of gay women. ACLU attorney Taylor Flynn says the case is special because Axtell made specific notes in DuPont’s file about her sexuality.

The notes included the following comments: “At the end of the visit, I told the [patient] that I felt uncomfortable treating her because of her lifestyle. I gave her the names of Dr. Tracy and Dr. Reuland to see in my place. The [patient] was very offended that I was prejudiced against her and was upset about that.”

John L. Supple, an attorney for Bristol Park Medical Group, in which Axtell practices, says its policy “has always been and will continue to be to not discriminate . . . in providing medical care.”

DuPont says the stress of the incident helped break up her relationship, but she and her partner are now in counseling. She’s speaking out about her discrimination case “to make the public aware it’s a violation.”