A New Key to Behavior

- Share via

Geneticists are the darlings of science. They have been so successful at unraveling the code of life, DNA, that their work is embraced not only as our best hope of curing cancer and other diseases but as a means of understanding human behavior. Genes, many scientists have come to believe, determine not only the shape of our bodies but the contours of our emotions.

But this notion is being carried to ludicrous extremes in some academic circles. For example, many medical researchers are trying to find a single gene sequence for depression, though complex emotions cannot be reduced to genes, much less a single sequence.

The ascendancy of genetics has also led some people to embrace questionable notions of human nature. Last year’s best-selling book, “The Nurture Assumption,” for instance, contends that genes, not parenting, are primarily responsible for how children turn out.

That’s why the emergence of a fast-growing but still little-known academic school of thought called memetics is welcome. Memetics is the science of memes, a word that biologist Richard Dawkins derived in 1976 from the word “memory” to refer to ideas, habits and beliefs that are passed from person to person by imitation. Just as genes ensure their survival by leaping from body to body via sperm or eggs, memes propagate by leaping from brain to brain. Ideas, styles and beliefs are passed from person to person, from generation to generation. What genes are to our bodies, memes are to the human culture and mind.

Genetics and memetics have in common the notion that humans, like all animals, are influenced by forces they don’t consciously understand and that don’t always act in their benefit. For example, the sneezing reflex is not something our body does to cure itself of a cold. Rather, it is the cold virus’ way of propagating itself: spreading its DNA through the air into another comfortable human host.

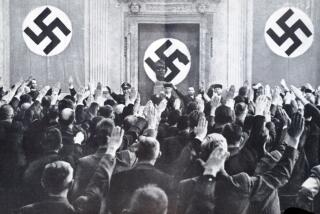

Memetics sees ideas as a kind of virus, sometimes propagating in spite of truth and logic. Its maxim is: Beliefs that survive aren’t necessarily true, rules that survive aren’t necessarily fair and rituals that survive aren’t necessarily necessary. Things that survive do so because they are good at surviving.

Memetics is still a new and primitive science, but it is already helping social scientists engineer better public policies. For example, the “rational expectations” school that dominates modern economics, which assumes that people will buy and sell goods in ways that serve their self-interest, has often failed to predict market behavior. Memetics offers insights into how subconscious notions can sweep a population like a flu bug. This could help economists understand how, for example, a rumor on the Internet leads a high-tech company’s stock to soar beyond reason.

Unfortunately, memetics has something else in common with genetics. It can be used to absolve people of personal responsibility, as in, “My memes made me set fire to the building, officer.” In her new book “The Meme Machine,” British professor Susan Blackmore argues that we humans are no more than “meme machines.” That’s taking memetics to the same unrealistic extreme as others have taken genetics.

Memetics ought to be supported but not glorified. For while we are clearly influenced by both our genes and our memes, we don’t have to be ruled by them.