Rafael Alberti; Spanish Poet Was Last Survivor of ‘Generation of 1927’ Artists

- Share via

Rafael Alberti, the influential Spanish poet who was the last survivor of the Generation of 1927 literary group, has died.

Spain’s national radio said Alberti died early Thursday at his home in his native town of Puerto de Santa Maria. He was 96.

Alberti, who was a contemporary of poet Federico Garcia Lorca, died from a lung ailment that had caused him to be hospitalized several times in recent years.

In a telegram to Alberti’s widow, Spain’s King Juan Carlos called Alberti “a remarkable poet who throughout his long life created works full of inspiration, promise and beauty.”

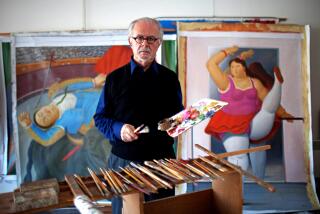

Alberti, who also was a dramatist and painter, was called “a poet of the proletariat” because of his ability to identify with Spain’s working class. He also was the first major Spanish poet to openly embrace communism.

Born in December 1902, Alberti left his hometown during his childhood when his parents, who were in the wine business, moved the family to Madrid. But he never forgot his Andalusian roots. His works often contained references to that region’s folklore, the language of the streets and vivid descriptions of the Bay of Cadiz.

But where Garcia Lorca had what many critics saw as an instinctive joy and melancholy to his poetry, Alberti’s work was seen as more cerebral.

He first received attention for his 1925 volume of poetry titled “Marinero en tierra” (Sailor on Land), for which he won the national literature award. Among his other collections are “A la pintura” (To Painting) and “Sobre los Angeles” (Concerning the Angels). He also wrote plays as well as two memoirs.

An early proponent of Surrealism, Alberti was one of the founders of the Generation of 1927, a loosely knit group of writers and poets that included Garcia Lorca, Vicente Aleixandre and Jorge Guillen.

The group took its name from the year Alberti, Garcia Lorca and other literary figures met in Seville to plan a yearlong homage to 17th century Spanish poet Luis de Gongora on the tricentennial of his death.

Years later, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda would recall that he “never again saw anything that could approach” the outburst of creativity he saw in this group.

In the 1930s, Alberti became a member of Spain’s Communist Party and his work became increasingly strident, drawing criticism even from allies such as Garcia Lorca.

Alberti “has turned Communist and is no longer writing poetry, even though he thinks he is,” Garcia Lorca said in 1933. Ironically, it was Garcia Lorca, not the more political although less well known Alberti, who later would be executed by Francisco Franco’s forces.

As the cloud of fascism continued to descend, Alberti visited Germany and witnessed the burning of the Reichstag. Upon returning to Madrid, he launched the revolutionary magazine Octubre (October). The first issue condemned nazism in Germany and its disregard for human rights.

His plays were political and highly controversial. In the book “Lorca: A Dream of Life,” author Leslie Stainton wrote that in the final performance of Alberti’s play “The Uninhabited Man” the author had the names of all jailed Republican leaders read aloud from the stage. At other times, Stainton wrote, fistfights would break out in the audience between Republicans and supporters of the monarchy.

During the Spanish Civil War of 1936-1939, Alberti toured the Republican lines giving poetry recitals and became a major propagandist against Franco.

Alberti immigrated to France after Franco took power and stayed there for two years before being expelled. He went to Argentina, where he lived for three decades, refusing to return to Spain while “enemies of the people” retained power.

In his later years in Argentine exile a sense of nostalgia for his homeland seemed to bring more harmony to his work. It was during this time that he published what may be his most famous work, “La Arboleda Perdida” (The Lost Grove).

In 1977, two years after Franco’s death, the poet went home to Spain for the first time in 38 years, his return seen by many as a bridge between the country’s dictatorial past and its democratic future. He was welcomed by more than 300 Communists carrying red flags as he stepped off the airliner.

“I’m not coming with a clenched fist,” he said, “but with an open hand.”

According to the Economist newspaper, Alberti’s work had something of a revival on his return to Spain. A gallery in Madrid showed his paintings while one of his plays had a good reception. Meanwhile, a publisher released a new edition of a Garcia Lorca text illustrated by Alberti. And the Communists adopted the painter-poet as one of their senatorial candidates from Cadiz. Alberti was elected.

“A poet is not being apart,” he said at the time. “He needs always to broaden his horizon. Politics will put me into closer contact with real people--with country folk, fishermen.”

Despite that sentiment, he found elected office not to his liking and quit not long after his election.

But he retained his belief in communism to the very end.

“I repent for nothing,” he said on his 90th birthday. “I am not an ex-Communist.”

He is survived by his second wife, Maria Asuncion Mateos, who was at his side when he died, and his daughter Aitana, named for the boat that took him to Argentina.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.