China at 50: Gains, at a Cost

- Share via

With much fanfare and the biggest display of military hardware in its history, the People’s Republic of China today is marking the 50th anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s Communist revolution. The country has traveled a huge distance since that epochal event, a half-century in which Marxism became the mold of a new China, one that sought to restore the glories and power of the old imperial China but stumbled time and again, unable for decades to find the politico- economic model that would deliver. It has begun to find a way now, and in the last two decades, particularly, China has been delivering a better life to many of its people.

These turbulent five decades, beginning with Mao’s righteous call for progress but also his many crackpot ideas--making steel in backyard furnaces, for instance--proved not to be a path to greatness and glory. Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, driven from the mainland to Taiwan, in fact found a better way.

Time and again Mao rallied the Chinese with programs designed to galvanize the people to Communist goals--the Great Leap Forward of 1958-60, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1965. He was the Great Helmsman, but his ship was constantly running aground. The Communists, still in power, now have seen their Marxist dogma of class struggle lose its meaning. The post-Mao leaders have traded in that ideology for a new credo--”To get rich is glorious.”

The revolution remains alive. Deng Xiaoping, Mao’s successor, succeeded in delivering pragmatic changes directed toward a life less onerous for everyday Chinese.

Mao put China through more than 20 years of wrenching political oppression and crippling economic experimentation, building a nation that could no longer be pushed around by superpowers. His reign also produced an isolated dictatorship dangerous to its neighbors.

China joined the war against the U.N. forces in Korea, battled with India and the Soviet Union over territory, helped install the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and supported the Communist forces in Vietnam. It persecuted those it saw as “war criminals, traitors, bureaucratic capitalists and counterrevolutionaries” at home. The victims of the purges numbered in the millions.

Deng, in the late 1970s, set China on a new course of modernization, opening the economy to outsiders, adopting far-reaching market reforms and establishing diplomatic ties with Washington. A pragmatist and a firm believer in bold economic reforms, Deng was nevertheless no democrat. In June 1989, troops under his orders massacred hundreds of students in Tiananmen Square as they protested Communist rule.

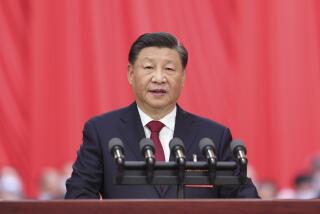

Now his successor, President Jiang Zemin, commands yet another “new” China. Economic reforms have produced remarkable results, fivefold growth since 1979. China has become the world’s 11th-largest trading country. It has swapped Marxist ideology for economic prosperity.

Old grievances against Europe have been corrected by the return of Hong Kong and Macao to China’s control. But mistrust of Washington endures, spurred by rising nationalism, the anti-American demonstrations following the May bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade and current tensions over Taiwan.

Problems will not be easily solved. Beijing’s fencing with Washington over its bid to join the World Trade Organization is an example. But life is better in China today. Fifty years after the Communist revolution, Beijing looks outward. It has taken progress in each of these five decades to reach this point, and the momentum continues.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.