Firm’s Patent Bids Alarm Gene Project Researchers

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A leading biotechnology firm has reported stunning progress in deciphering the human genetic code and is already seeking patent protection for 6,500 of its discoveries, fueling fears that fundamental advances in a genetic revolution now underway could end up the private property of a few wealthy drug companies.

Celera Genomics, a Rockville, Md.-based subsidiary of PE Corp., reported last week that it has already laid out the sequence of 1.2 billion “letters” of the human genome in five weeks, a seemingly spectacular achievement. While that still leaves the company behind a decade-old, publicly funded effort, the pace is so fast that company officials say they could complete the entire sequence by 2001 or even sometime next year.

But the firm’s announcement that it has filed “provisional patent applications” on some of its early results has rocked the scientific world and angered many government-funded scientists because it appears to contradict Celera’s past assurances that this basic information would remain in the public domain.

Company executives said they were “going to make sure the data was publicly available, but I always figured their data release [practices] would change,” said Richard D. Wilson, co-director of gene sequencing at Washington University in St. Louis, one of five centers leading the publicly funded effort. “It’s not going to be as free and clear as it sounded.”

Celera’s research is parallel to the massive Human Genome Project, which involves academia, federal agencies and private companies. The results of that effort would be made available to the scientific community.

The race to discover the entire human genetic code is one of the most important scientific efforts underway, one that could lead to a revolution in the next century in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. The human genome is the genetic blueprint, or code, that directs the growth and health of every member of the species.

Deciphering the code--sequencing 3 billion letters spelled out by DNA molecules--is an enormous task that has been compared to the moon landing or splitting the atom. It is expected to result in a deep understanding of the most basic aspects of human body functions.

Some scientists worry that patenting gene sequences and putting such basic information in private hands will discourage research outside of the drug companies that own the rights to the information. If that proves correct--and the Celera executives dispute it--scientists fear that many of the promised medical advances might never take place.

News of Celera’s patent applications prompted Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Riverside), chairman of a House Science subcommittee, to say he might schedule a hearing in January on public access to genetic information. Last year Celera executives assured Calvert’s panel that publicly financed scientists would have wide access to company findings and the firm would seek only limited patents.

Celera officials defended their actions as vital to protecting the interests of the company’s shareholders, and they said that their policy has not changed.

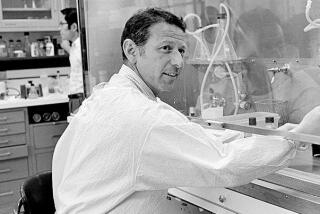

“It is disturbing to me that anyone wants to make this into something negative,” said Celera’s president and chief scientific officer, Craig Venter. “There are no losers with this system. Every researcher in the world will have the human genome years ahead of time.”

To be sure, Celera is not the only private sector company seeking to patent human genetic information. Human Genome Sciences, also of Rockville, and Incyte Pharmaceuticals, a Palo Alto, Calif., firm, have also filed substantial patent applications.

But Celera is the only company to declare that its aim is to sequence the entire human genetic code and to beat the public effort to the information. In doing so, it has made itself a lightning rod in the debate over how far ownership rights should extend over such basic information.

“The sequence of the human genome is fundamental information,” said Francis Collins, who heads the National Human Genome Research Institute. “It is the beginning of the road of discovery and not near the end of it.

“To make it useful requires lots of additional steps that will be inhibited if you put up a lot of tollbooths early on that road and make people less interested in traveling on it at all.”

The human genome is made up of DNA, a chemical that contains a complete set of instructions to govern the activities of every cell in the body. It is arranged in chromosomes--23 pairs at the center of every cell.

The DNA is built of smaller chemicals, called bases--the letters of the genetic code. These in turn spell out the equivalent of words--called genes--each one containing the instructions for making a vital protein or acting as an on-off switch to control myriad microscopic activities that make life possible.

The federal Human Genome Project began in 1990 with no obvious competition. But that changed 18 months ago when Venter and his partners announced that they had a plan to complete the genome much more quickly than the public effort--making use of hundreds of brand-new, high-speed sequencing machines that it would purchase from a sister subsidiary of PE. What had been a painstaking task had suddenly become a race to the finish line.

Collins said Friday that the federally funded effort is expected to complete a rough draft of the genome by spring and could complete the final readout by 2002, a year ahead of schedule.

“The Human Genome Project is close to having 1 billion assembled base pairs” out of the 3 billion, said Wilson, the Washington University scientist. By contrast, said Wilson, although Celera claims to have 1.2 billion base pairs, the company’s pairs do not appear to be assembled or neatly organized, and so are much less useful.

From the outset, publicly funded scientists have worried that Celera would stake a proprietary claim to genetic information and restrict its dissemination to drug companies and others that pay handsomely for it. Venter especially went out of his way to reassure people that such fears were unfounded.

In testimony before Calvert’s subcommittee last year, the Celera executive said the firm would “release data into the public domain at least every three months” and would seek only 100 to 300 patents for very specific things.

“Our action will make the human genome unpatentable,” he said.

On Friday, both Venter and PE President Tony L. White asserted that their plans have not changed.

The provisional patents would give the company and its clients--drug companies Amgen, Novartis and Pharmacia & Upjohn--a year to decide which of the genes they would pursue. The company’s small genomics research group, White said, will probably pick out no more than 300 from all the genes uncovered in completing the sequence.

The company still plans to post its raw data on a public Web site but in a way that would prevent academic scientists and competitors from downloading it. “Once we’ve gone through and looked for the intellectual property jewels in it,” White said, “there’s no reason not to make it available.

“We’re trying to strike the right balance between doing public good and protecting commercial interests for our shareholders.”

Asked whether Celera’s plan for public access squares with what publicly funded scientists believe is necessary, Wilson, the Washington University scientist, said: “It doesn’t square at all. Look, I can’t get access to the data unless maybe I’m willing to pay.”

*

Jacobs reported from Sacramento and Gosselin from Washington.