It’s Scientists’ Dream to Understand Dreams

- Share via

Bake that cake! Push 100 birthday candles into it! This year, after all, is the 100th anniversary of Sigmund Freud’s landmark book, “The Interpretation of Dreams.” Dreams, Freud said, contain coded symbols of all our darkest unconscious desires.

According to Freud, my recent dream about vacuuming the house is no doubt deeply revealing, although I maintain it’s about nothing more than guilt over being a slob. (Sometimes a vacuum hose is just a vacuum hose.)

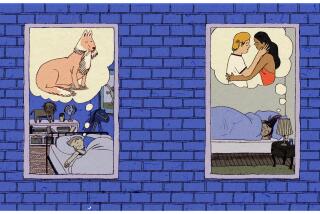

In fact, Freud’s dreamy ideas are still unproven (sometimes a theory is just a theory). So are everyone else’s. Some scientists think dreams help us work through emotional problems. Others think dreams are just the brain sort of daydreaming while we sleep. Others think dreams delete unneeded memories so brains don’t get too fact-clogged. Bottom line, say experts: Dreaming is still a big, black box. No one really knows why we dream, if we need to and what dreams mean.

FYI: In the past, scientists have tried influencing dreams by, for instance, spraying water on people while they slept. (Sometimes it worked--the person might start dreaming of rain. Other times, the sleeper might just report dreaming of drinking a glass of water.)

They’ve also obtained evidence that other species dream. In a classic, decades-old study, cats were seen to run, pounce and hiss--almost as if they were acting out dreams--when their bodies were released from the paralysis that usually accompanies sleep by cutting certain nerves.

Fighting the Age-Old War on Halitosis

I just received another tongue scraper in the mail (though this second one isn’t battery-powered, like the earlier one). Also enclosed: one surgical mask and a bottle of breath spray. (“Take the hint, man,” says a co-worker.)

The hint, obviously, is that readers want to know more about remedies for halitosis. Here’s what a quick jump online revealed.

If you had lived in the times of the ancient Hebrews, according to halitosis researcher Mel Rosenberg of Israel’s Tel Aviv University, you might have whipped up a cure composed of dough, water, olive oil and salt. Or maybe you’d have simply held a pepper in your teeth (but which pepper, Rosenberg doesn’t know).

For centuries, the Iraqis have chewed cloves to mask breath odor--which probably helped kill the bacteria responsible, since cloves contain antimicrobial chemicals.

We can’t speak to the effectiveness of these three remedies, but all are vastly preferable to this one we found, from ancient Greece: Take one head of hare, add three mice with their intestines removed, but not the liver. (Got that? Intestines--no. Liver--yes.) Finally, grind to powder, mix with chalk and rub onto teeth with unwashed wool.

How can you even doubt?

The Tragedy of Vegetable Addiction

And now for something completely different: nicotine in vegetables.

Yes! That’s right! Flicking through the latest copy of the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (as we are wont to do), we stumbled upon an article from Austrian scientists who ground up various plants from the deadly nightshade family and analyzed them for the presence of nicotine.

At first we were puzzled. After all, if someone’s eating nightshade, why should they be worried about addiction or anything else long-term, for that matter? Then we learned that the nightshade family includes nonpoisonous plants such as potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants and peppers, and that’s what the scientists are interested in. These plants (and teas and cauliflower) contain nicotine.

Anyway, as far as we can gather from this and other research, quite a few plants contain low levels of nicotine, which may help protect the plant against insects. (Nicotine is sometimes used as a commercial insecticide.) The tobacco industry has argued that you might get as much nicotine from eating veggies as you would from secondhand smoke, but secondhand smoke researchers splutter at this.

So here’s what we want to know: If vegetables contain nicotine, how come it’s so hard to get kids to eat them? OK, one can find very occasional references to vegetable abuse in the medical literature. We unearthed a fascinating paper about a patient with a carrot craving, for instance--we can’t begin to guess what Freud would have said--and we’ve heard of people turning orange from carrot bingeing. But my child and yours? Addicted to eggplant? In your dreams.