An Activist’s Vision

- Share via

As a boy in the 1940s, growing up in the “Valley of Hearts Delight,” as the Santa Clara Valley was called, John Kouns would earn his pocket money by picking prunes, apricots and walnuts in the hot, dusty fields. He was lucky to make 8 cents a tray and even luckier if the boss paid him at the end of the day and not a few months later.

Little did Kouns know that more than 30 years later, he would be one of many photographers to bring the plight of destitute farm workers to the forefront of America’s consciousness. From 1965 through the early ‘70s, Kouns became one of the leading chroniclers of the farm worker labor rights struggle led by Cesar Chavez.

His work was not as a photojournalist but as an activist, organizing photo exhibitions throughout Central and Northern California to raise money for the cause and educate people on the farm workers’ plight.

His work from that era, along with that of five other photographers and seven visual artists, is featured in “An American Leader--Cesar E. Chavez,” an exhibition at the Latino Museum of History, Art and Culture in downtown Los Angeles. The work chronicles Chavez on his road to reforming agriculture’s treatment of farm workers from 1965 through his death in 1993.

The exhibition, which continues through Aug. 18, also features the work of photographers and union activists: Victor Aleman, Oscar Castillo, Emmon Clarke, George Rodriguez and Jocelyn Sherman. Also on display are related paintings and murals by artists including the late Carlos Almaraz.

“I would call myself more of a concerned photographer,” Kouns said in a telephone interview from his home in Sausalito. “The camera is a passport, and it has taken me to places I wanted to go. The camera kind of legitimizes my presence and gives me an opportunity to do something about injustices.”

Kouns’ photographs have become a part of America’s memory. Whether they show U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy grilling overzealous sheriff deputies or half a dozen habit-clad nuns taking bread to the fasting workers, his images are some of the more striking of the exhibition.

Wright’s ‘Native Son’ Was His Epiphany

Born in Alameda in 1929, Kouns was raised in an average middle-class household. His parents were not politically minded, but at a young age Kouns became aware of the racism and injustice surrounding him. There were few Mexicans and no blacks at his high school. But he was blessed, he said, with a liberal social science teacher who suggested that Kouns read Richard Wright’s “Native Son.” The book was an epiphany.

Distraught by the hardship Wright described in his book, Kouns went to his teacher and demanded to know what he could do to help. “Why don’t you join the NAACP?” the teacher told him. And so Kouns, a 15-year-old white kid with curly brown hair and blue eyes, did.

“My parents were apolitical,” Kouns recalled. “We couldn’t talk too much about race because [my father] was polarized in his opinion and so was I. He was kind of a redneck from Kentucky. [Segregation] just seemed so obviously not right to me.”

He became interested not only in racial injustice but also in the rights of workers. By his mid 20s, Kouns had already become a member of three unions: International Longshore and Warehouse Union when he worked at a cannery, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters when he worked at a printing factory and the Wire Service Guild when he joined United Press International in 1958.

While in college, Kouns majored in physical education. But in the early 1950s, while in the Navy, he took a photography course that changed his life. He found that his activist, artistic and creative impulses were all satisfied by making pictures. He then enrolled at the New York Institute of Photography.

“I just thought there was more to life than being a coach,” he said.

Kouns Was Influenced by ‘The Grapes of Wrath’

By 1963, the country was on the verge of turmoil. The South was palpably tense as the civil rights movement gained strength, and Kouns wanted to be a part of it. So he took a bus to Selma, Ala. He photographed the civil rights movement off and on for nearly two years, including the march to Washington and the bombing of the 16th Street Church in Alabama.

Kouns had been heavily influenced by the Depression-era photography of Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee and by John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.” Following his lifelong passion for agriculture and its workers, Kouns was turned on to the United Farm Workers’ movement.

Kouns was there from the beginning, in 1965, when the name Cesar Chavez was unknown to most of the country. Ever the egalitarian, Kouns said he never intended to focus on Chavez. The workers, he said, were just as important to the movement as its leader. But Chavez’s aura and the near spellbinding attention he garnered nonetheless made him a regular subject of Kouns’ work.

“He had a more personal type of charisma rather than being showy or big,” Kouns recalled. “His humility and concern [were] his charisma rather than anything else.”

Kouns also captured moving scenes of gratitude among the farm workers; an example is his photograph of an elderly man standing in the union hall, hat over his heart, light illuminating his face Rembrandt-like, as he thanked the union for fixing his car. Kouns still chokes up when he recalls the image.

“It was such a beautiful thing,” said Kouns, his voice breaking as he recalls that moment from 35 years ago. “It was so important because, to a farm worker--next to his family--his car is his right arm. You can’t get from job to job or to the picket line without a car.”

Kouns captured some of the most gripping images of the day. For example, in a series of photographs chronicling Kennedy’s 1966 Senate hearings in California on migratory labor, Kouns used the natural light in the room to highlight Kennedy, cigarette smoke curling around him, creating an aura that is almost angelic. The subjects of Kennedy’s attention, the Tulare County sheriff and his deputies, are veiled in darkness, reminiscent of stereotypical shadowy, obese Southern sheriffs.

Kouns said he didn’t intend that effect but was pleased with the results.

“I could say I planned it that way, but that would be a big lie,” he said. “That’s just the way the light was.”

Eager to show his photographs outside of the gallery scene, Kouns began touring what he called the “Guerrilla Camera.” Taking his mounted pictures to union halls, schools, churches and libraries, Kouns traveled throughout Central and Northern California--anywhere he could show his work, raise money for the cause and earn a few dollars himself.

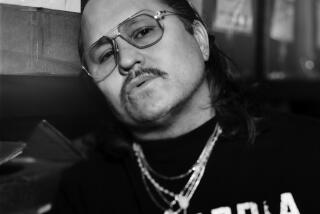

Kouns’ modesty, sweet smile and tender eyes belie the firebrand pro-union sentiment he has held all his life. It was just luck and timing, he says, that led him and his camera to witness some of this country’s most important news events.

He continues to support the farm workers with his photographs, traveling to Florida, Salinas, Modesto and other agricultural areas to capture the conditions. At 71, he said he intends to continue until he can no longer hold a camera.

“It was a very important time in my life, and I was really lucky to have been there,” Kouns said. “It created a situation in which my photography, I think, has had some importance.”

*

* “An American Leader: Cesar E. Chavez,” Latino Museum of History, Art and Culture, 112 S. Main St., downtown Los Angeles, (213) 626-7600. Daily, 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Ends Aug. 18.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.