Female Athlete’s New Clothes Are Not What Some Think

- Share via

I’m naked. I’m writing this with one hand, clutching a suggestively draped towel with the other, while crouched behind a soccer ball. I’m waiting for the schoolmarms and the soreheads and the Robespierres to haul me off to the Thought Police at any second.

OK, so I’m not really naked. I just said that for effect. Consider it a salute, my way of showing solidarity with Jenny Thompson and Brandi Chastain and other female athletes who have bared themselves lately, to the utter panic of certain sports prudes and creaking, old-school feminists.

There is a nudity epidemic in women’s sports. First, there was Chastain nude behind a soccer ball for Gear magazine, and now everywhere we look female athletes are romping through the pages of magazines unclothed. Four Olympic swimmers posed in a single towel for Annie Leibovitz in Women’s Sports and Fitness. Last month’s issue of Esquire was full of semi-nude Olympians. Most recently and controversially, there is Thompson, arguably the world’s greatest swimmer, shirtless in Sports Illustrated, her chest covered only by her clenched fists.

The same old-girl gang wants to slap the moral manacles on Thompson for the same old reasons. The Women’s Sports Foundation responded with a page-long, single-spaced condemnation, and USA Today quoted a scandalized swim mother who worried about the effect of the image on her kid.

This outcry comes though the photograph is utterly harmless. There is not a single, actual, verifiable nipple in sight. Which begs the question of what, exactly, is going on here?

Women worry that an unseemly photograph carries high stakes in public policy: if an athlete poses frivolously, there’s another strike against Title IX. But the self-appointed moralists and feminist guardians completely miss the point and misread the photograph.

The picture isn’t offensive. It may even be an important image for this reason: Thompson isn’t showing off her breasts. She is showing off her muscles. It’s a crucial distinction.

And a wonderful piece of cultural jujitsu. Thompson’s pose is not about pornography, and it’s only sort of about sex. With her fists clenched, wearing a Wonder Woman outfit, the eye goes to her biceps first and next to gasp-evoking muscles in her legs. We are not witnessing the decline of Western Civilization here or the steady decay of morals. What we are seeing firsthand is a redefinition of femininity into something more complicated and brawny, and it’s high time.

“I think it’s strong and beautiful,” Thompson says.

Photographer Heinz Klutemeier says, “It’s not a sexual picture at all. It was not about taking her clothes off. She’s the perfect Olympian, and the Greeks and the Romans would have fought to sculpt her.”

If younger women resist the term “feminist,” maybe it’s because the movement so often lacks muscle and tends to assume we don’t have control over our arms and legs. Thompson is not a bimbo or an object or a victim, and she doesn’t need lessons in sexual politics or comportment from anybody. She is a 27-year-old of serious intellect, a Stanford graduate on her way to medical school. Nobody made her take her shirt off, and she was thoroughly aware of the meaning and imagery she was playing with when she did it. She is a pinup girl for subversion, not sex. In flexing, she co-opted the terrible old cliches, the extreme and distorted images of female athletes as either come-hither sirens or butches. For once, here is a picture in Sports Illustrated of a woman who asks to be admired for her form rather than ogled for her figure.

At least three members of the U.S. women’s soccer team thought the picture was great. Chastain and a handful of her teammates immediately picked up the phone to call Thompson’s agent, Sue Rodin.

Ordinarily, I don’t take Sports Illustrated’s side against the Women’s Sports Foundation. The WSF correctly bashes the magazine for its chronically smirky and hostile treatment of women.

“I’ve sided with them [the WSF] on occasion, when we’ve put women on the cover only if they’ve been stabbed or abused,” Klutemeier says. “I’m just sorry the picture of Jenny wasn’t on the cover. I’d welcome a picture like that before I would the swimsuit issue.”

There is a chief difference between the portrait of Thompson and the kind of pictures that appear in the swimsuit issue. One is a nude in the classic sense, while the others are just naked pictures.

Nudes aren’t about sex, they’re about human form. Artists throughout time have used them to define the body ideal, to explore perfection and proportion. But the ideal changes all the time. If the 1950s ideal was Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe, today’s audience would say they need to lose 20 pounds and tone. And changing views of nudity almost invariably provoke social discomfort and dispute, if not outright screaming.

One famous example leaps to mind: a picture of a young woman reclining on a couch, a slipper hanging from her foot. When it was first displayed, audiences hissed and threw garbage at it because it was not acceptably veiled with enough classical metaphor. You can view it in Paris in the Musee D’Orsay. Go to the main hall, ask for the works of Manet, turn right, and there you’ll find her. Her name is Olympia.

Show the portraits of Thompson and her fellow athletes to an art historian, and he sees something both innocent and interesting. Stuart Horodner, the director and curator of the Bucknell University art gallery, interprets the trend of female athletes disrobing as a pointed statement on the difference between nude and naked.

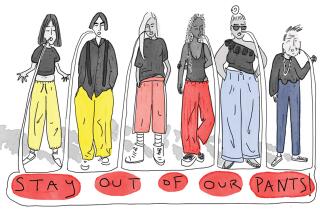

“I think there’s something quite spectacular about them,” he says. “The people posing, and the people taking the pictures, are obviously aware of these two distinct histories of nude versus naked, and these women are taking their bodies back, reclaiming them.”

So maybe the only organization with a right to be upset is Nike. It pays big money so athletes will display the swoosh, and now women want to, whoosh, take it off.

Then there is Jenny Thompson’s mother, Margrid. Surely she is the litmus test: if the picture doesn’t bother Thompson’s own mother, it shouldn’t bother the rest of us. And what does Margrid think?

“People need to lighten up,” she told Thompson’s agent.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.