Archeologists Probe Mystery of the Mounds

- Share via

MONROE, La. — The Indian mounds deep in the northeast corner of Louisiana don’t look like much. Two guys with a backhoe and a bulldozer might have needed a day or so to shove dirt into that oval of mounds and ridges.

Until a timber company clear-cut the trees and thickets at Watson Brake in 1981, nobody even realized they had been built to create a greater shape. And it took nearly two decades after that to discover that they are the oldest known grouping of mounds in the Western Hemisphere.

They might not have survived without the dogged crusade of a former Census Bureau worker and amateur archeologist named Reca Jones.

The mounds and their purpose are a mystery, but they have become a touchstone for archeologists studying the Middle Archaic period--around 6000 to 3000 BC.

Work started here a millennium before Tutankhamen was born. The much larger concentric series of earthworks about 60 miles away at Poverty Point would not be built for 1,500 to 2,000 years. The Mayan pyramids in central America and the Anasazi cliff dwellings in the American West were even further in the future.

“Many people thought the Middle Archaic was people running around doing hunter-gathering things for 3,000 years,” said Mark Barnes, a National Park Service archeologist. “They were much more sophisticated than we thought.”

Jones had known since she was a child that there were a couple of old Indian mounds there.

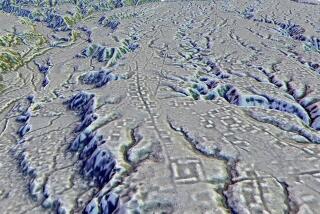

Then Willamette Industries Inc., which owned half the site until the Archaeological Conservancy bought it in 1996, cut the trees. Suddenly Jones could see that there were more mounds than she’d realized, with ridges connecting them into a giant egg shape. It was about 300 yards from end to end and 200 yards across.

“I was here almost the whole time Willamette was here, saying, ‘Don’t get on the mounds! Don’t get on the mounds!’ ” Jones said. Willamette complied.

Then she asked a Harvard archeologist to map the site with her, but he was interested in the ceramic age, which began about 3,000 years ago. It wasn’t until July 1993 that Joe W. Saunders, the state’s archeologist for that region, drilled the first sample.

Bit by bit, the evidence added up. The find went public in 1998, in Science magazine.

Jones’ discovery, her years of work to get a professional to excavate it, and her work in the excavation and reconstruction won her the Society of American Archaeologists’ Crabtree Award for amateur archeology.

Scientists have dated the remains to 5,400 years ago. Some of the oldest mounds seem to be trash heaps covered with dirt. Sometimes the builders covered an area where they had lived and worked, camped on the new surface, then covered it over again.

But others are just dirt on dirt. And all of the work appears to have begun at about the same time.

About 60% of the oval is a natural ridge that once overlooked swamps and a tributary of the Arkansas River. But why build it higher, and why close in the rest?

It probably wasn’t flood protection; the land already was well above flood level.

Bones and shells reveal that the mound builders ate lots of fish, mussels and aquatic snails, and some turtles and small animals. The leftovers also indicate that the people came in the spring and left in the fall.

Before Saunders and Jones began their work, the intricate earthworks at Poverty Point were the oldest known mound complex in North America.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.