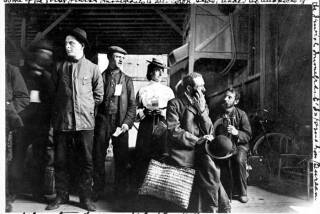

Russian Jews Put New Face on Poverty in New York

- Share via

NEW YORK — When Alla Volodarskiy arrived in the United States, she tried to brighten the Brooklyn apartment she and her husband, Yefim, rented for $730 a month by sweeping out the cockroaches and placing rugs over the finger-sized cracks in the floor.

But frustration flooded the thoughts of this retired professional couple, who consolidated nearly six decades of memories into four suitcases to move from the former Soviet Union to the United States as refugees in 1993. In Kiev, earnings from Alla’s job as an economist for a railway supplies factory and Yefim’s job as second in command in Ukraine’s building materials department provided them with an expansive two-bedroom apartment.

When they chose to leave Kiev to move here, they joined legions of the former Soviet Union’s Jewish intellectual and professional elite in shaping this fact: Jewish poverty here is at its highest level since 1945.

The number of Jewish New Yorkers whose incomes fall at or below 150% of the national poverty level (about $16,900 for a couple) has increased by more than one-quarter since 1990, from 145,000 to 185,000, according to a study last fall by the Metropolitan New York Council on Jewish Poverty.

Those numbers, combined with the more than 100,000 Jewish New Yorkers whose incomes are about 150% to 200% of the poverty level, mean that about one-quarter of New York’s Jewish population is living in or near poverty, said William Rapfogel, the council’s executive director.

The city’s overall poverty rates dwarf those numbers. As many as 57% of New Yorkers live at or below the poverty level.

But these Russian Jewish immigrants are putting a new face on poverty.

The most needy include well-educated refugees who are older than 55 and have arrived here in the last decade. Men more than women seem to fall into this category, Rapfogel said.

“The men at that age group act as if their life is over,” Rapfogel said. “Whatever dreams and aspirations they had in the old country they can’t achieve here.”

His age, high blood pressure and heart problems prevented Yefim, now 74, from finding a job in the United States. Alla, 63, said she could not find a job at a food store because of her age and limited ability to speak English. She enrolled in junior college courses in English grammar, speech and U.S. history.

“I thought maybe I’ll learn English and have some profession,” she said. But her own problems with high blood pressure cut short her schooling.

After paying rent each month on their first apartment, the Volodarskiys lived on $80 in food stamps and $120 from federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and other benefits for refugees.

“It was not comfortable, not nice,” Alla says.

Immigration historians agree that recently settled Russian Jewish refugees are one of the best-educated immigrant groups in the United States. More than 60% of Russian immigrants have bachelor’s degrees, and more than 15% have advanced degrees, according to a recent study by the New York-based Research Institute for the New Americans.

But age and language barriers prevent refugees from applying their education in the U.S. labor market. Rabbi Joseph Katz, who manages three apartment buildings that house mainly low-income Russian Jewish immigrants, has tried to match some of them with employers. But the most recent immigrant he tried to help, a Russian Jewish engineer who worked in a factory assembling space rocket testing equipment for 20 years, could not find a job as a washing machine mechanic because he speaks little English.

Still, Russian Jewish immigrants like the Volodarskiys are happy to stay. Their financial struggles here are relative: Pensions in the former Soviet Union add up to about $25 a month, said Zvi Gitelman, a political science and Judaic studies professor at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

“We like America,” Alla Volodarskiy said. “We are very sorry we came [to the United States] late.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.