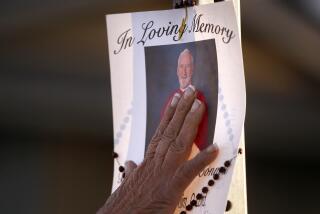

Robert Runcie; Ex-Archbishop of Canterbury

- Share via

LONDON — Former Archbishop of Canterbury Robert Runcie, the outspoken cleric who led the Church of England through a decade of turmoil and presided over the marriage of Prince Charles and Princess Diana, has died after a six-year battle with prostate cancer. He was 78.

Runcie, a vocal critic of former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government during his 1980-91 tenure at the helm of the church, died late Tuesday night at his home in Hertfordshire outside London.

He led the church through emotional theological debates over the ordination of women, marriage after divorce and the modernization of the liturgy, and he will be remembered, in particular, for his historic invitation to Pope John Paul II to come to Canterbury in 1982.

“He was a wonderful raconteur, a delightful man, and we will all miss him enormously,” said the current archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey. “I don’t think he really liked controversy in any shape or form, but he was brought into it, as inevitably any archbishop of Canterbury is.”

“He encapsulated the Anglican tradition of thoughtful holiness,” said John Henry Moses, the dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Born in Liverpool in 1921, Runcie served as a tank officer in the Guards Armored Division during World War II and received the Military Cross after the invasion of Normandy in 1944. He attended Oxford before being ordained, eventually becoming Thatcher’s surprise choice for archbishop in 1980.

Runcie was initially averse to taking the post, saying he didn’t have enough of the skills required.

“That’s what made me a reluctant archbishop,” Runcie said earlier this year. “I think the archbishop should be among the resolvers, make mission statements, and stand up for them. But that’s not what I’m like.”

Runcie became a critic of the Thatcher government’s fight with striking coal miners in the mid-1980s, accusing the Conservative leadership of treating the miners like “scum.”

He called Britain’s nuclear arsenal “lunatic” and antagonized the Thatcher administration by routinely praying for all the dead in the Falklands War. He was criticized for underplaying Britain’s victory during a thanksgiving sermon he offered at the end of the war in 1982.

On Wednesday, bishops from throughout the church mourned Runcie’s death, saying that what they will miss most is his lightheartedness and humor.

“I once heard Robert say that nobody should be put in charge of anything unless they had a sense of humor. He certainly passed that test,” said the Roman Catholic archbishop of Westminster, Cormac Murphy-O’Connor. “He possessed a wonderful wit. He had a sense of the absurdity of things and was always amazed that he was archbishop of Canterbury.”

The Rt. Rev. Frederick H. Borsch, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, said that he had become a friend of Runcie during the archbishop’s visits to Southern California and when the two worked together in the Anglican Consultative Council and in planning a 1988 conference of bishops.

“Robert Runcie was a wise and gentle archbishop of Canterbury,” Borsch told The Times. “He had a marvelous gift of humor and also of humility, which made him and his leadership attractive to many people.”

Despite his reputation for controversy, Runcie tried to ease tensions where he found them. Having presided over the wedding of Charles and Diana in 1981, he later tried to help the couple through a troubled marriage. But his outspokenness got him into trouble there too.

In his 1996 biography of the archbishop, Humphrey Carpenter quoted Runcie as saying that the royal marriage had been “arranged” and describing Diana as dim.

“When you began on abstract ideas, you could see her eyes clouding over, her eyelids became heavy,” he was quoted as saying. He later added a note to the book saying, “I have done my best to die before this book was published.”

Diana, who died in a 1997 car crash, said she would “never forgive his treachery.”

Runcie pushed a reluctant church to take a more liberal line on second marriages but was more conservative on the divisive issue of ordaining female priests.

He said he was not personally opposed but argued that ordaining women would hamper overtures to Roman Catholics and Orthodox Christians and split the church.

“If anybody thinks that it is easy and it doesn’t cost very much to your personal soul to pursue the middle way, if anybody thinks that it’s simple trying to please everybody like a chameleon, let them come and try and ponder the Scripture and say their prayers and try to hold the church together,” Runcie told the Guardian newspaper before his retirement.

The year after Runcie retired, the General Synod of the Church of England voted to permit the ordination of women as priests. On another controversial issue, Runcie later acknowledged that he had knowingly ordained homosexuals.

He also had pushed the church into working in Britain’s inner cities, and raised millions of dollars to fund projects for the poor and unemployed. But the last years of Runcie’s tenure as archbishop were overshadowed by the kidnapping of his aide Terry Waite in Lebanon. Waite went to Beirut in January 1987 to negotiate the release of other hostages and ended up one himself.

Waite was freed after five years, and both men admitted afterward to tensions between them. Runcie described Waite as a “grandstander,” and Waite complained of a lack of support from the archbishop.

But Waite said Wednesday that Runcie “was a good man in every respect.”

*

Times staff writer Myrna Oliver in Los Angeles contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.