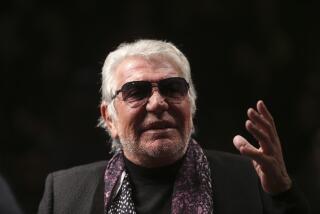

Enrico Cuccia; Key Italian Financier

- Share via

ROME — Enrico Cuccia, the reclusive Sicilian financier whose skill at building corporate alliances made him a legendary architect of Italy’s state-led industrial revival after World War II, died Friday. He was 92.

In failing health since an April operation for prostate cancer, Cuccia was admitted to the Monzino Foundation Cardiological Center in Milan on Thursday. At the family’s request, the cause of his death remained as unknown as many details of his secretive life.

Cuccia’s death was first announced in Rome at a meeting of the Italian Bankers Assn., whose members stood for a moment of silence. His passing was described as a landmark in Italy’s transition from a state-guided economy dominated by a few families to one that is more market-oriented and competitive--a shift the banker resisted.

“He represented the best of Italian capitalism, which is now undergoing profound transformation,” Prime Minister Giuliano Amato said.

Fiat’s Giovanni Agnelli, the country’s leading industrialist, added, “All of us should be grateful for his contribution to the growth of our country.”

As founder and chairman of Mediobanca, Cuccia bought minority shares in key companies and became their banker, masterminding a web of mergers that made him the country’s most powerful financier. That network, with his bank at the center, included Fiat, Pirelli, Olivetti and the life insurance giant Assicurazioni Generali. For decades he defined Italy’s business elite.

His entry in Who’s Who in Italy says the banker “played a key role in all the major financial operations carried out in Italy” after the war.

Mediobanca began as a state-controlled institution in 1946, when the government had a monopoly on long-term loans and commercial banks were barred from holding direct equity in companies. Its mission was to rebuild postwar Italy.

Technically a civil servant, Cuccia turned the bank into the so-called smart drawing room of Italian capitalism--a clubby refuge where Italy’s big family-controlled companies made deals beyond the scrutiny of the press and minority shareholders. The bank eventually went private.

“Mediobanca acquired a far-reaching influence over the destiny of half the Italian economy. It became the force to be reckoned with,” American journalist Alan Friedman wrote in “Agnelli and the Network of Italian Power.”

Agnelli summed up the banker’s influence this way: “What Cuccia wants, God also wants.”

Cuccia’s most famous remark--”Shares are weighted, not counted”--captured his skill at using shareholders’ pacts to defend companies from takeover and to control them with small amounts of capital.

Biographers say that Cuccia succeeded on his keen intelligence, extraordinary memory and ruthlessness with rivals. “He has the morals of a medieval monk--one of those monks who can also kill for a good cause,” former Olivetti chief Carlo de Benedetti wrote last year.

But it was the banker’s absolute discretion that won the trust of the rich and powerful. His secrecy was as legendary as his ice-blue eyes, his dry wit and his reserved manner, which spawned one of his nicknames, “the British Sicilian.”

“There are two sins for a banker,” he liked to say. “The first is running off with the safe, and the second is talking.”

Throughout half a century behind headline-making deals, he never gave an interview. The most journalists ever got was a shy “buongiorno” as the stooped, thin banker walked from his Milan apartment to Mediobanca’s headquarters near La Scala opera house at 6:30 most mornings. Little was known about his private life.

Born in Rome, he got a law degree and went to work at Italy’s central bank in 1932 before moving to IRI, the state industrial holding company, in 1934, when Italy was under Benito Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship. He married Idea Nuova Socialista (New Socialist Idea) Beneduce, a daughter of IRI’s leftist boss, in 1939. They had two daughters and a son.

At Mediobanca, Cuccia was behind many controversial deals, including one that gave Fiat control of the Milan newspaper Corriere Della Sera and allowed the Libyan regime of Col. Moammar Kadafi to realize windfall profits on the purchase and sell-back of Fiat stock.

Critics faulted him more for resisting the privatization of Italy’s economy and trying to thwart the rise of entrepreneurial newcomers such as media magnate Silvio Berlusconi and clothier Luciano Benetton in the 1980s and ‘90s.

In 1982, at the age of 75, he left the board of Mediobanca but kept an office and the title honorary chairman.

The banker’s death came days before the scheduled liquidation of IRI, the giant state holding company that launched his career. Mediobanca remains Italy’s leading merchant bank, but its future is now uncertain.

“Cuccia has died and the world that he represented doesn’t exist anymore,” said Fabio Tamburini, author of a biography about the banker. “The world of state-held companies is finished, IRI has come to an end, and the big families of Italian capitalism have changed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.