Cardiologists Debate Safety of Super-Aspirin Testing

- Share via

BOSTON — Super-aspirin is turning out to be a super-failure, perhaps even a deadly one.

Five years ago, when large-scale testing began, researchers were optimistic that the drug would improve on the plain two-cent variety, which is still the most important medicine for heart disease.

But study after study has ended badly--even shockingly. Now some believe the pharmaceutical industry should call it quits. Stop the testing, they say, because super-aspirin may actually kill more volunteers than it saves.

The drugs are a class of blood thinners known technically as IIb/IIIa antagonists. They are already injected to keep blood vessels flowing smoothly after angioplasties and mild heart attacks. But drug companies envisioned a larger market for these medicines in a new pill form.

Instead, they would be taken by millions of people with bad hearts to ward off heart attacks, strokes and death. Just like aspirin, the thinking went, only more effective and, of course, a lot more expensive.

(The medicines are not to be confused with an entirely different class of drugs--the cox-2 inhibitors, including Celebrex--which are used to treat arthritis and are also sometimes called super-aspirin.)

The companies have spent hundreds of millions to prove super-aspirin works as well in practice as it ought to in theory. About 42,500 volunteers have tested four slightly different kinds in five large studies.

Each time, though, the outcome was the same. Super-aspirin not only fails to prevent heart attacks; it actually kills people.

Enough, says Dr. Eric Topol, cardiology chief at the Cleveland Clinic. He figures that in those five studies--two of which he directed--between 150 and 200 volunteers probably died from the treatment itself.

Nevertheless, the testing continues. A study of DuPont Pharmaceutical’s super-aspirin, called roxifiban, began last July. It will enroll 2,200 patients in North America and Europe by the end of this year.

Should DuPont let the study go on? Is it even ethical to do so? Top-tier cardiologists argue both sides.

Some agree with Topol. Considering the results so far, these drugs are too dangerous to keep testing on people. Others contend the study’s risks will be slight if it is stopped at the first hint of trouble. Furthermore, there are reasons to think roxifiban will work better than the other super-aspirins, they say, and it would be tragic to give up on a treatment that could still prove to be a lifesaver.

An effective super-aspirin could certainly be that. As good as aspirin is, it reduces the risk of death from heart disease by only about 20%, and doctors yearn for something more powerful.

Alarming Numbers

But doubts that super-aspirin will ever be the answer have grown over the last two years. The latest setback came shortly before Christmas. A committee of doctors held its quarterly meeting at a Boston hotel to go over data from BRAVO, a big study of a super-aspirin called lotrafiban. (Cardiologists love to give their studies catchy acronyms. BRAVO stands for Blockade of the IIb/IIIa Receptor to Avoid Vascular Occlusion.)

The committee, called the Data and Safety Monitoring Board, worked independently of the study’s lead doctors and corporate sponsor, SmithKline Beecham. Its job was to make sure the study was not hurting anyone. It had the authority to peek at the ongoing results, something the other doctors involved could not do.

The study was massive, involving 9,200 patients on four continents. In the mathematics of heart research, such large numbers are necessary to reveal small effects of the drug.

On that December day, the numbers showed that the death rate was actually higher among the volunteers getting lotrafiban--2.7%, versus 2% in the people taking dummy pills. This amounted to 30 extra deaths among the lotrafiban users--30 deaths that may have been caused by the drug itself.

But was the drug truly to blame, committee members wondered. Those extra deaths might have happened by chance. Just two weeks earlier, the number of deaths in the two groups was the same. Maybe in time the numbers would go the other way.

“If this had been the first time through with an oral IIb/IIIa antagonist, we might not have stopped the trial. We would have assumed that it might have been just a blip,” says one committee member, Dr. James Tcheng of Duke University.

But this was not the first time through. It was the fifth. Each study showed essentially the same thing: more deaths in people taking super-aspirin. It was time to stop BRAVO.

The committee sent a letter headlined “URGENT PLEASE READ,” to the 700 hospitals in 30 countries with patients in the study. The message: Take them off the drugs.

Also signing the letter was Topol, the study’s chairman. It was his second bad experience with a super-aspirin. Two years ago, Topol headed a study called SYMPHONY, which looked at Roche’s sibrafiban. It also ended in failure.

Blood Clots Suspected

Now Topol toted up the results. Combining the five big studies, he found that taking super-aspirin increases people’s risk of death by 36%. A statistical fluke? Unlikely. The chance of that was perhaps one in 100,000.

Many of the extra deaths seemed to be cardiac arrests, which could have been triggered by blood clots, the very thing super-aspirin is supposed to prevent. But still, no one was sure.

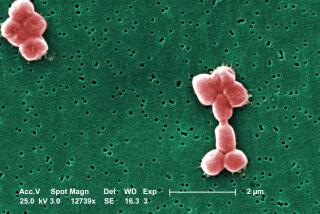

In their injected form, IIb/IIIa antagonists are widely used and considered highly effective. They work by subduing platelets, the blood cells that form clots. When injected, the drugs can stifle platelets’ tendency to clump together by 90% or more. This is useful in some hospital situations when the risk of dangerous clots is especially high. But the probability of unintended and possibly disastrous bleeding is too high to continue this treatment indefinitely.

The pill form is less powerful. It inhibits platelets by about 50%. Still, this is potent medicine, and it seemed logical that it would help people with serious heart disease, since misguided clots are the primary trigger of heart attacks and strokes.

“Everybody thought this would be the next zillion-dollar drug,” says Dr. John Ambrose of St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York City.

Researchers have several theories about what went wrong. Maybe super-aspirin somehow triggers heart cells to commit suicide. Or perhaps it sets off a wave of inflammation.

But the leading theory is that the pills fail because of their halfway action. In hindsight, it appears that partially disabling the body’s clot-making machinery this way is a bad idea.

These drugs, whether injected or swallowed, work by sticking to the fibrinogen receptor. This blocks the spot on the surface of platelets that ordinarily lets in chemical signals telling them to form clots.

After someone takes a pill, the amount of medicine in the bloodstream gradually falls until it’s time to take another one. As these blood levels grow low, more and more of the platelets’ fibrinogen receptors are uncovered. But the cells do not like to have their receptors blocked and then reopened this way. It leaves them in a twitchy, hair-trigger state, ready to clump into clots with little provocation.

So, as a result, many think super-aspirin has a paradoxical effect: It inhibits platelets, but it also activates them, and the net effect is more clots, not fewer.

Although there is evidence supporting this theory, Topol cautions that no one knows for certain whether this explains why the first four super-aspirins tested were dangerous. Therefore, he says, there is only one safe option.

“I think there should be a moratorium on this drug class,” he says. “At this point, I think it’s unethical to continue the PURPOSE trial.”

PURPOSE is DuPont Pharmaceutical’s study of roxifiban, the only super-aspirin pills now in human testing.

Criticism of the minutiae of study design is common in academic medicine. But calls for big studies to stop in their tracks are rare, especially coming from experts of Topol’s stature.

Word of his opinion quickly spread on the Internet. Among other things, Topol is editor in chief of theheart.org, a Web site read by heart specialists. It carried two stories about his misgivings.

The bad BRAVO results, along with Topol’s criticism, could not be ignored. So doctors running and monitoring PURPOSE met to reconsider whether to continue.

The research had already been redesigned once. DuPont originally intended a much larger study in people with mild heart attack and unusually bad chest pain, the same patients involved in the other five studies.

But after their rivals’ early failures, they decided to try their drug in patients with severely blocked arteries in the legs. These people are also at high risk of heart attacks, and the company hoped they would respond better to the drug.

The PURPOSE doctors voted to keep going, but with one major change: They would tighten the guidelines for stopping the study at the first hint of unexpected deaths. Under the new statistical rules, they have a 90% chance of catching a one-third increase in the death rate before the study is finished. Under the original plan, there was a 55% chance of this.

But the more conservative rules introduce a new risk--a 20% chance that the study will be needlessly stopped because of a statistically meaningless temporary uptick in the death rate.

“You can’t ask for a more highly monitored trial than the one we’re doing,” says its director, Dr. William Hiatt of the University of Colorado. “Just a handful of excess mortality, which could happen by chance, will stop this trial.”

He and others say the study should go on because the super-aspirin being tested is better than the ones that failed. It binds more tightly to the platelets and does not fade away as much between doses.

“So far, it looks very good in every test done, and it is perfectly reasonable to test it. We are doing that as carefully as possible,” says Dr. Christopher Cannon of Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a member of the data monitoring board.

Experts Disagree

But opinions among cardiologists are split over whether the drug is different enough to reasonably expect a better outcome. Among those in doubt is Duke’s Tcheng.

“I agree with Eric [Topol] 100%,” he says. “I think the roxifiban trial should be stopped. Unless you have a completely different therapeutic approach, not just a different drug, you are more likely than not to repeat history.”

Dr. Donald Easton, a neurologist from Brown University who co-chaired BRAVO with Topol, also admits to misgivings about the study. But he thinks it should continue because of the possibility that it will produce a useful, needed medicine to prevent the leading cause of death.

“I try to keep in mind on the positive side that these drugs do work in other situations, and the disease we are treating is not acne,” Easton says. “It’s death and disability.”