Taliban Tells Neighbors Not to Aid U.S.

- Share via

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — Afghanistan’s ruling Taliban threatened neighboring Islamic countries with war Saturday, including invasion, if they grant the United States use of airspace or military bases in the quest to capture suspected terrorist Osama bin Laden.

The warning, directed principally at Pakistan, came as the government here pondered for a third day its detailed response to an American “wish list” for help to fight terrorism.

A senior Pakistani military source said the country’s leadership has agreed to meet all U.S. requests for assistance in tracking down those who carried out the attacks Tuesday against the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and the hijacking of the plane that crashed in Pennsylvania. But President Pervez Musharraf’s Cabinet and the national security council met for four hours Saturday to debate the details and the implications of that decision.

In a 30-minute news conference Saturday evening, Foreign Minister Abdus Sattar repeatedly dodged reporters’ demands for the precise commitments that Pakistan is willing to make.

“We’re in the process of discussions regarding specific details,” Sattar said. “Our response will be consistent with our stand against international terrorism.”

Sattar also linked support for the U.S. to Pakistan’s obligations to fight terrorism under United Nations resolutions passed in the wake of the attacks.

The military source said Musharraf is expected to begin holding a series of meetings today designed to prepare public opinion for his decision to aid the Americans, to be followed by an address to the nation later this week.

U.S. officials have announced that Pakistan is fully on board with all U.S. requests and have repeatedly expressed thanks for the pledges of support. But here, at least publicly, that response is being more carefully crafted and presented as merely an agreement in principle.

The elaborate precautions reflect the politically volatile nature of the Bush administration’s requests to Pakistan--requests that include intelligence sharing, border closings and the use of Pakistani airspace in pursuing Bin Laden and his associates.

One Pakistani journalist at the news conference posed the country’s choice this way: “Is Pakistan going to back a distant and not-so-friendly state, the United States, to participate in a war against a friendly, neighboring Muslim state?”

Sattar answered that he would not speak of a “war” with Afghanistan.

It apparently was Musharraf’s commitment to help the United States that triggered Saturday’s threat of invasion from the Taliban.

The United States has long been angry at the Taliban for refusing to turn over Bin Laden, an avowed enemy of America whom President Bush on Saturday called the prime suspect in masterminding last week’s attacks.

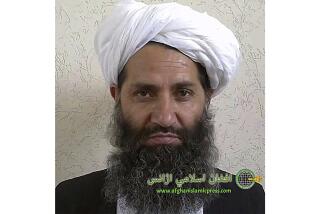

The Taliban’s spiritual leader, Mullah Mohammed Omar, has refused to surrender Bin Laden, and he warned Afghans on Friday to be ready to fight and possibly die in a war with America to defend Islam.

Then, in a statement Saturday, Omar pointed out the possibility of that war spreading to Pakistan or other Islamic countries, such as Tajikistan, that might be called on to help the United States.

“If neighboring or regional countries, particularly Islamic countries, gave a positive response to the American demand for military bases, it would spark extraordinary danger,” the statement declared. “Similarly, if any neighboring country gave territorial way [access] or airspace to USA against our land, it would draw us into an imposed war.”

All of Afghanistan’s neighbors--from Iran in the west to Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan across the north to Pakistan on the east and south--have majority Muslim populations.

The statement asserted that it was possible that the Taliban might be forced to invade a fellow Islamic country with its moujahedeen, or freedom fighters.

“The moujahedeen would have to enter the territory of such country,” said the statement, distributed by Afghanistan’s embassy in Islamabad.

At the Pakistani news conference, Sattar rejected the warning and said that war with Afghanistan was not being considered.

“We’ve had a very strong relationship of solidarity with Afghanistan. We’ve not always agreed on policy, but we remain committed to maintaining a dialogue,” he said.

In an apparent reflection of already heightened tensions, however, U.N. sources said Saturday that the border with Afghanistan had already been closed. Sattar appeared to confirm the report.

“Pakistan has taken certain precautions in view of the tense situation. We’ve increased vigilance on our borders. We don’t want our borders to be violated,” he said.

Early today, in what it characterized as a security measure, the government also announced that it was withdrawing all nonessential diplomatic personnel from the Afghan capital, Kabul.

Iran said Saturday that it would seal its border with Afghanistan to prevent a possible influx of refugees, the official Islamic Republic News Agency reported.

As Pakistan edges closer to publicly meeting U.S. demands, a groundswell of dissent is emerging from editorial commentators, political analysts and students.

The former head of the country’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency, Lt. Gen. Hamid Gul, argued in an interview that it would be disastrous for the United States and for Pakistan to try to go to war against the Taliban, which he described as as a force of skilled and motivated warriors with the complete loyalty of the Afghan people.

“Pakistan must not help anyone attack Afghanistan physically because it is not in its interest to do so,” he said. “Everyone who has underestimated Afghanistan has paid a terrible price.”

Many Pakistanis with a strong sense of history are especially nervous about a decision to cast the country’s lot once again with the United States. They are also resentful that American policymakers seem to have forgotten the risks to which such ties have previously exposed their country.

In an interview, Rifaat Hussein, the chairman of the department of strategic studies at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad, said the country’s experience of alliances with the U.S. is likely to make people question the wisdom of aligning with it again.

He cited a series of occasions when standing alongside the U.S. has brought risks to his country. He noted, for example, how Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev threatened to make the Pakistani frontier city of Peshawar a prime nuclear target because it had served as a base for the U2 spy plane flown by Francis Gary Powers that the Soviet Union shot down in 1960.

Hussein said Pakistan risked Moscow’s wrath again in 1971 by facilitating then-National Security Advisor Henry A. Kissinger’s historic diplomatic opening to China; in the 1980s, when it helped the West supply the Afghan resistance against Soviet invaders; and in 1991, when it joined the coalition against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq despite public protests at home.

Despite all that, he said, the United States has put sanctions on Pakistan for developing a nuclear weapons capability meant to counterbalance India’s. More recently, America has shown signs of tilting toward India on regional issues.

“We have been the most essential ally of the United States, and now the Americans come and ask what side of history we’re on,” Rifaat Hussein said. “That’s unfair. The United States hasn’t done a . . . thing to help us in Kashmir,” the Himalayan region claimed by both Pakistan and India.

“If the Pakistani people react with anger,” Hussein said, “then there’s a history here.”

Gul, the former intelligence chief, agreed that public sentiment in Pakistan has turned against American policies. “The whole nation is anti-American, especially in these circumstances,” he said.

One of the first public shows of dissent in Islamabad came early Saturday evening when a group of more than 200 religious fundamentalists gathered peacefully at a central market holding placards with anti-American slogans and messages of support for the Taliban.

“Americans should stop bullying Muslims,” read one sign.

But anti-Americanism is not restricted to religious fundamentalists. When a prominent Pakistani journalist received a phone message Saturday from an unknown caller urging a boycott of McDonald’s outlets in the country, he traced the call back not to a political radical but to the president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in one of Pakistan’s major cities.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.