Ex-Enron CEO Is Set to Play Blame Game

- Share via

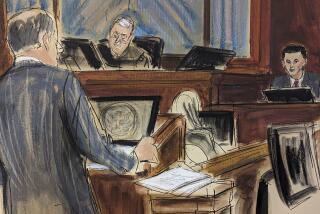

When former Enron Corp. Chief Executive Jeffrey K. Skilling appears at a hearing on Capitol Hill today, he will be pressed by lawmakers on his failure to control controversial Enron partnerships.

But if his dealings with Enron’s internal investigative committee are a guide, he is almost certain to point to aggressive underlings as the main culprits in a series of complicated financial transactions that eventually brought about the energy trader’s collapse.

Unlike other Enron executives scheduled to testify, Skilling is not expected to invoke his 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Skilling has declined interviews and is giving no clues as to what his testimony will be before the oversight and investigations subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

Still, a broad outline of what Skilling might say can be gleaned from what he told a special investigative committee of Enron’s board, which issued a searing report that concluded Skilling and other executives failed to adequately oversee the off-balance-sheet partnerships that helped prompt Enron’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing Dec. 2.

“He was certainly in the center of the storm,” said Rep. James C. Greenwood (R-Pa.), chairman of the House subcommittee that will question Skilling under a “friendly” subpoena.

“He either believes that he’s innocent and wants to come in and defend himself--I give him that presumption--or he thinks he’s so smart, he can fake us all out,” Greenwood said. “He’s going to be, I think, the most fascinating witness” today.

Skilling was president and chief operating officer--and for a brief six months, chief executive--during the blossoming of Enron into the seventh-largest U.S. company by revenue and the world’s largest energy trader.

But a good deal of that growth was phantom, aided by financial sleight of hand through the use of a grid of off-balance-sheet partnerships and transactions designed to make Enron’s fiscal statements look good by hiding mounting debt and losses, according to the report prepared after three months of investigation by University of Texas Law School Dean William C. Powers and two other Enron directors.

The report sets the stage for a likely blame-off between Skilling and Enron’s former chief financial officer, Andrew S. Fastow, who ran two of the partnerships and enlisted his lieutenants to invest. Although Fastow had indicated to other employees that Skilling was in the know on significant transactions, Skilling repeatedly told the committee otherwise.

Enron employees involved in the partnerships--most notably Fastow himself--enriched themselves through questionable transactions between the partnerships and Enron, the Powers report shows. Meanwhile, errors--some deliberate--in accounting for those transactions inflated company earnings by more than $1 billion during a 15-month period ended Sept. 30, the report concluded.

Powers, in testimony before the House panel Monday and Tuesday, spread blame broadly, but singled out “a fundamental default of leadership and management” particularly from Skilling and Kenneth L. Lay, Enron’s longtime chairman and chief executive.

Skilling knew about and was involved in setting up some if not all of the partnerships, which were run by Fastow and others, and carried such names as LJM, Raptor and Chewco. But how much control Skilling exercised over the partnership transactions is the subject of dispute in the report.

Skilling claims to have exercised little oversight over critical business transactions, despite the fact that the board was told he was doing so. His recollections of crucial conversations that would place him in the know on some of the most controversial deals are faint or nonexistent, the report shows. But his claims are consistently contradicted by the accounts of others.

For example:

* Oversight of the LJM partnerships: The board required that all LJM transactions be reviewed and approved by Skilling as “the senior member of management responsible for the LJM relationship.”

At an October 2000 board meeting, Fastow informed the board that Skilling would approve transactions between Enron and the LJMs, and “a review of Fastow’s economic interest in Enron and LJM was presented to Skilling.”

Skilling told the panel “he may not have been present for Fastow’s remarks” at the meeting, although board minutes show he attended.

His signature was missing from nearly all of the LJM approval sheets, which Skilling was supposed to review, the report said.

Skilling told the committee he never reviewed the actual amount of Fastow’s stake in the partnerships, instead reviewing only “a handwritten document [from Fastow] showing only that Fastow’s economic stake in Enron was substantially larger than his economic stake in LJM1 and LJM2.”

* The Raptors: The Raptors were special-purpose vehicles created beginning in April 2000 to allow Enron to hedge part of its merchant investment portfolio. But the board committee concluded that the Raptors were not true hedges, instead improperly using gains in Enron’s stock price to keep losses off the books.

Of key concern was a restructuring of the Raptors in 2001 designed to mask more than $500 million in losses. According to the report, “senior Enron employees” told the committee that Skilling--recently elevated to CEO--”was aware of this problem and was intensely interested in its resolution,” even calling to personally thank one accountant who worked on the project once it was complete.

If those accounts hold up, “Skilling both approved a transaction that was designed to conceal substantial losses in Enron’s merchant investments and withheld from the board important information about that transaction,” the report said.

Skilling, however, told the committee he recalls being informed “in only general terms” of the problem and barely understood it.

* The McMahon interaction: Former Treasurer Jeffrey McMahon, who is now president and chief operating officer, told the committee that he met with Skilling in March 2000 to express concern over the LJM partnerships and Fastow’s conflict of interest.

McMahon provided the committee with written talking points he prepared for his meeting. According to those, he addressed Fastow’s conflict of interest, pressure placed by Fastow on him to do deals that weren’t in the best interest of Enron shareholders, and the fact that bonuses were affected by the scheme, his included.

*

Times staff writers Richard Simon in Washington, Jeff Leeds in Houston and Thomas S. Mulligan in New York contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.