Architects of Genocide

- Share via

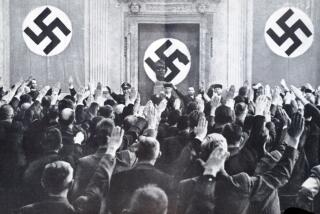

The gas chambers and crematories at Auschwitz-Birkenau annihilated thousands of Jews each day, creating the haunting specter of modern technology harnessed to the goal of genocide. But before that, high-ranking Nazi officials meticulously organized mass shootings of hundreds of thousands of Jews (and some other groups). Even after the establishment of extermination camps, shooting continued where it was the more efficient method in Poland and in conquered areas of the Soviet Union. If the gas chambers had never existed (or if they had been destroyed by Allied bombs late in the war), Nazi Germany still would have tried to carry out a “Final Solution of the Jewish question” through other means.

To explain how large numbers of people became mass murderers, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Richard Rhodes cites both the ideological motivation of Nazi leaders and the socialization of leaders and followers to use violence. Drawing heavily from the testimony of perpetrators brought to trial and from survivors and witnesses of the mass shootings, Rhodes supplies a vivid account in “Masters of Death” of this first stage of the Holocaust.

Rhodes correctly contends that the techniques to carry out the mass murder of an entire people had to be invented.Once the Nazi leadership decided to eliminate what it perceived as a mortal threat from the Jewish “race,” they were in uncharted territory. There was no precedent for eliminating a population that they estimated at more than 11 million across Europe (the number used at the 1942 Wannsee Conference). The Nazi regime became more and more firmly committed to genocide of the Jews and to the decimation of other populations in a vast new Eastern empire to be settled by Germans. Officials explored different ways of carrying out their barbaric objectives.

The Einsatzgruppen were battalion-size units formed by the Security Police and SS Security Service, known as the SD, which liquidated thousands of Poles and Jews in the fall of 1939. Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and chief of the German Police, and Reinhard Heydrich, commander of the Security Police and SD, decided to employ Einsatzgruppen on a much larger scale during the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Jews and Communist officials were their main targets.

For decades, historians gave four Einsatzgruppen (about 3,000 men) “credit” for killing more than 700,000 Jews, basing their findings partly on summaries of the killing operations prepared in Gestapo headquarters in Berlin. (These reports were uncovered after the war and were used to help convict a group of Einsatzgruppen officers in a U.S. trial that Rhodes covers briefly in an epilogue.)

But through painstaking archival research, historians have discovered that the Einsatzgruppen were but one component of the Nazi shooting apparatus. Battalions of the Order Police, selected regiments of the SS army and units of Ukrainian and other non-German police all played substantial roles as executioners in the East. Their combined manpower considerably exceeded that of the Einsatzgruppen. Himmler also employed key regional commanders in the war against the Jews in the East. The first stage of the Holocaust was a multifaceted operation with different components.

Rhodes does not limit himself to the Einsatzgruppen, but there remains a need for a more detailed comparison of the composition and behavior of the various units involved in the mass shootings.

High Nazi officials feared the adverse psychological effects of mass shootings on the executioners. Rhodes notes that Himmler was sensitive to this problem--he blanched when he witnessed a mid-August 1941 execution of Jews at Minsk. The SS and police regional commander for Central Russia, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, quickly urged more consideration for the welfare of his men. (Bach-Zelewski later suffered a breakdown.) The sequence of events suggests that Bach-Zelewski’s complaint to Himmler initiated a period of experimentation with alternative methods of killing, including poison gas in mobile vans.

A separate Nazi program to rid Germany of those deemed genetically defective--the mentally and physically disabled--was by 1940 already gassing tens of thousands with carbon monoxide. Eventually, extermination camps that would use carbon monoxide were constructed in areas that are today in Poland and were used to kill Jews who had been transported there. Officials at Auschwitz-Birkenau also tested the insecticide Zyklon-B, which led to even more lethal facilities combining the gas chamber and crematorium.

Rhodes draws upon work done in the 1990s by American criminologist Lonnie Athens to explain how people are socialized to use violence: First, they are brutalized; then they become belligerent. They begin to exhibit violence to defend themselves against perceived threats and then they become “virulent.”

Rhodes believes that a form of this model also explains how policemen and SS men became the violent instruments of Nazi policy, although it requires him to make broad generalizations such as: “Certainly brutalization was the common lot of most children in Germany at the beginning of the twentieth century.” But what is the evidence that child-rearing in Germany was more brutal than, for example, in Russia or Austria-Hungary in that era? If such differences were minimal, how does such brutalization help explain the Holocaust?

Rhodes also draws on research by political scientist Michael Mann to demonstrate that a sample of nearly 1,600 Nazi perpetrators shows a high percentage were people who had previously been part of extreme political movements that tended to use violence. Mann’s important work is in some tension with detailed research by Holocaust historian Christopher Browning about the composition of one police battalion.

Mann’s sample of perpetrators brought into trial proceedings may or may not reflect the much larger population of untried perpetrators. Rhodes, however, essentially agrees with Browning that there were several types among executioners: eager and enthusiastic killers, those who followed orders and a small minority who declined to participate or soon sought to withdraw.

Rhodes adopts the now common, but not universal, view that Hitler first decided to liquidate Jews in the East, then made a later decision to reach across the entire continent for all European Jews. His account of Nazi decision-making blends the work of scholars with different and sometimes incompatible views about the timing of key Nazi decisions.

Readers are given little hint of interpretive disagreements. In addition, Rhodes pays little attention to the latest trend among historians that local and regional officials sometimes influenced central decisions.

In his well-researched book, “The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps,” historian Michael Thad Allen finds that another type of perpetrator, engineers who worked for the SS, shared a positive belief in German racial supremacy, negative stereotypes of other “races,” especially Jews and sweeping aspirations to rebuild the world according to “German will” and without moral restraints.

This group of technocratic “visionaries” does not fit the model Rhodes uses: They did not need a long-term pattern of socialization into violence to work slave laborers to death. Granted, these SS engineers (even some who worked on the construction of gas chambers) were more removed from their victims than the Einsatzgruppen.

The Einsatzgruppen were indoctrinated about the menace Jews supposedly posed to Germany shortly before they began their grisly work. Mass murder was given legitimacy, sometimes with the claim that Hitler himself had authorized the policy. Unconditional obedience to orders, without regard to traditional morality, was a cardinal principle of the SS, and few policemen in Nazi Germany, whether they belonged to the SS or the Nazi Party or not, were accustomed to defying orders.

When they received orders to kill--even to kill women and children--there were more than enough willing executioners. Repetition desensitized them more often than it caused them to refuse an order or to break down emotionally.

Although there is no clear evidence that the SS engineers or the Einsatzgruppen required long-term pattern of socialization to violence, Rhodes’ and Allen’s works should contribute to better understanding of Nazi Germany and its crimes. They also remind us that the potential for genocide depends more on motivation and organization than on the level of technology.

Ask the Rwandans.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.