Bacteria Can Play Villains or Good Guys in Biofilm

- Share via

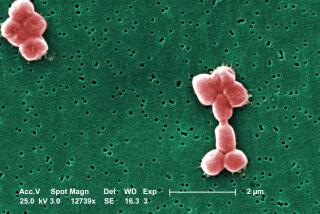

When I think bacteria, I think teeny, tiny individual blobs living in splendid isolation. These days, however, microbiologists know that those diminutive cells often choose to hang out in stuck-together clumps.

And when they do, beware. Just as kids (to say nothing of adults) are influenced by mob dynamics and act out in different, silly or downright dangerous ways, bacteria in crowds change their stripes too.

In the case of bacteria, the changes they make are anything but dumb. For instance, when disease-causing microbes form these layers--known as biofilms--they become much tougher.

Antibiotics that fight the free-swimming bugs just fine lose their clout as much as a thousandfold when the blighters clump together.

That’s why bacterial biofilms--in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis, in tough urinary tract infections, or sticking to the walls of catheters--are so hard to wipe out.

Far from being a random clumping down, forming a biofilm is a calm, crisply orchestrated business. Say an E. coli cell is swimming along inside a bladder, flipping its flagella this way and that way. All of a sudden, the bug reaches a nice, solid surface (say, the bladder wall). It sticks to the surface, turns all kinds of genes on and off, forms a colony. The colony covers itself with a thick, gooey, sugary slime, with lots of E. coli hidden deeply within. Presto! A drug-resistant biofilm is formed.

Should this be getting too grim, here are some other, less life-threatening biofilms: slime that forms in a week-old vase of flowers; bugs that obligingly chomp up sewage at waste treatment plants; ones in lakes that feed fish, and thus ultimately provide food for noble beasts like the American eagle; and the sticky plaque covering our teeth.

And we can revel in the fact that things could be even worse for our teeth and other parts of our body if we didn’t have ways to keep biofilm formation in check.

Lurking within our sweat, tears and nasal mucus is a chemical, lactoferrin, newly discovered to have biofilm-busting powers.

Scientists in Iowa City, Iowa, and Evanston, Ill., discovered this and recently wrote about it in the journal Nature.

They were studying a microbe called Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which infests the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis. Lactoferrin, they found, stops this bug from forming biofilms by depriving it of iron.

Pseudomonas swims in a kind of purposeful way; the scientists call such swimmers “ramblers.” Ramblers, as their name suggests, keep movin’ on.

When they reach a surface, the ramblers normally change their swimming pattern. They become squatters--they hang around, clump up and form a biofilm.

But in the scientists’ test tube studies, adding lactoferrin--and thus depriving the microbe of iron--abruptly altered matters. Squatters became scarce. Ramblers were the norm. Biofilms just didn’t form.

Scientists hope that understanding all these nuances--the genes turned on and off, the steps involved in making biofilm bugs more tough, mean and virulent--could eventually lead to new drugs that can better fight troublesome infections.

Finally, if you want to learn more about biofilms--and get a giggle as well--visit the silly but informative Web site, instruct1.cit.cornell.edu/Courses/biomi290/Horror/Openingpage.html. Here, two cartoon pudgy bacteria, a la Ebert and Roeper, review movies with biofilm themes. Click on different images in such bacterial cinematic classics as “One Flew Over the Petri Dish” to learn where biofilms lurk in nature and which ones help us, harm us or stay solidly neutral, like the Swiss.

Two thumbs up!

*

If you’d like to suggest a topic, write Rosie Mestel at L.A. Times, 202 W. 1st St., Los Angeles, CA 90012 or e-mail her at rosie.mestel@latimes.com.