Fundamentals Redux

- Share via

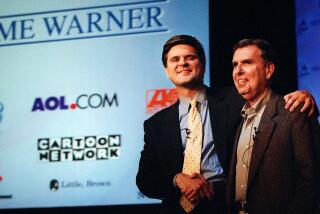

Even success stories like teen hit machine Britney Spears and blockbuster writer John Grisham weren’t enough to save Thomas Middelhoff, the head of the conglomerate Bertelsmann, from being fired Sunday. From Vivendi Universal’s Jean-Marie Messier to Deutsche Telekom’s Ron Sommer to AOL Time Warner’s Robert W. Pittman, global boardrooms are deciding--to borrow the title of Grisham’s first novel--that it’s A Time to Kill.

European business titans like Messier and Middelhoff wanted to emulate, even surpass, their aggressive American brethren, creating big digital media empires that would ride the Internet wave to prosperity and turn them into celebrities. But conservatism is the new/old style as companies retrench.

Some of the purging is as symbolic as it is practical. Consider Messier. In France, he became cultural public enemy No. 1 when he moved to New York and touted the American business model.

Messier transformed a water utility company into a media titan worth about $50 billion at its peak, with Universal Studios and USA Networks among its holdings. No one could really figure out the value of the empire constructed by Messier because it became impossible to get an overview of his various acquisitions. But the $17.1 billion in company debt that Messier accumulated during his buying spree loomed ever larger.

No sooner did the board of directors in Paris force Messier’s resignation than Sommer and Middelhoff came under scrutiny. After Sommer initiated a deal to buy VoiceStream in 2000 and invested heavily in online services, Deutsche Telekom stockholders saw continuation of a share price plunge that had started earlier that year. The German firm suffered losses of more than $3 billion in 2001.

Middelhoff never put Bertelsmann into massive debt, but he purchased Napster, a blunder that made his other questionable Internet investments look good by comparison. Middelhoff also adopted the United States as his home, calling himself “an American with a German passport.” He didn’t even want Bertelsmann referred to as a German company. But the family that has a controlling interest in Bertelsmann rejected the idea of taking the company public and possibly losing control.

Though Americans have a higher tolerance for corporate swashbucklers than Europeans, the fall of Pittmann certainly shows a new desire to respect business fundamentals like making money.

It’s fair to wonder whether the backlash might end up going as overboard as the grandiose pronouncements about new business models did in the 1990s. Capitalism requires risk-taking and innovation. But a breathing spell is certainly in order. Not every day at the stock market is supposed to be a Grisham-like thriller.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.