U.S. Weighs Risk of Smallpox, and Risk of Smallpox Vaccine

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Los Angeles County paramedics Pat Long and Eric Buege make medical decisions every day that save other people’s lives. Soon they might face one that could save their own.

This week, an advisory panel in New Orleans will recommend whether the government should loosen its grip on the nation’s stockpile of smallpox vaccine, which has been kept under wraps since the disease was eradicated worldwide in 1980.

In light of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and subsequent anthrax mailings, government officials are debating whether to release the vaccine to health and emergency workers and, perhaps, millions of other Americans.

“This is a difficult decision to make,” said D.A. Henderson, one of the world’s leading authorities on smallpox, during a forum Saturday in Washington. “There is no right answer. It’s a balancing of risk.”

For Long and Buege, taking the vaccine isn’t a simple choice. There’s an estimated 1- to 2-in-a-million shot that the vaccine itself could kill them, and a 1-in-100,000 chance of causing serious illness, such as severe rash, infection or brain inflammation.

Their families might also suffer health problems. Studies have shown that 20% of vaccine- related complications occur in people who were not vaccinated but came into contact with someone who was.

The Pomona paramedics must balance those risks against the unknown odds that terrorists might one day use the lethal smallpox virus as a weapon and that they would be called upon to respond to the attack.

“I don’t want to take the risk of the vaccine, for me or my family,” Buege said, adding that his views might change if a smallpox attack occurs.

Long, his partner, is less concerned and said he would likely do whatever health officials recommended. “There are so many other things that could kill us. Smallpox is the least of my worries.”

It’s a dilemma that soon could face millions of Americans. A smallpox terrorist attack could be catastrophic in the United States, where routine smallpox vaccinations ended 30 years ago. Smallpox mortality rates in the unvaccinated top 50%.

On the other hand, if the government resumed smallpox vaccines for the entire U.S. population today, an estimated 300 citizens could die of complications and thousands more would have serious health problems.

“The vaccine is one of the least safe of licensed human vaccines,” said Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Routine smallpox vaccinations in the U.S. ended in 1972, when health officials deemed that the health risk of the vaccine was greater than the risk of the virus.

That’s why U.S. health officials are moving cautiously as they weigh whether to re-release the vaccine, which has only been provided to lab workers at the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta and others who handle the virus.

On Thursday in New Orleans, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices will make a recommendation about the vaccine to Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy G. Thompson. He will make the final decision.

In the absence of a confirmed smallpox attack, few health experts expect the panel to recommend releasing the vaccine to all Americans, though polls suggest that more than half of the general population would take it if offered.

A tougher call for the CDC will be whether to make the vaccine more widely available to the general public after a confirmed terrorist attack.

Under current CDC policy, if a smallpox attack takes place, the vaccine will only be given to those people who come into direct contact with people infected with the virus. That strategy, which also was known as “ring vaccination,” helped health officials beat naturally occurring outbreaks in the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s.

But some public health officials fear the ring vaccination strategy would be less effective against a deliberate terrorist attack, particularly in the U.S., where the population is highly mobile. For example, if a terrorist infected with smallpox traveled on New York City subways for a week during rush hour, how would health officials be able to track down all potential contacts?

Instead, many are calling for the CDC to change its policy and recommend broader vaccinations in communities hit by an attack.

According to a study presented Saturday, vaccinating an entire city such as Los Angeles after a smallpox attack that affected about 1,000 people would confine the death toll to about 500 people, according to Edward Kaplan of Yale University’s School of Management. Using the CDC’s current policy, more than 3,000 deaths likely would occur, he said.

“Ring containment simply will not work in this kind of situation,” said William Bicknell, a former Massachusetts health commissioner and professor at Boston University’s School of Public Health.

Bicknell supports a gradual resumption of routine smallpox vaccinations for all Americans, with the exception of small children, who are more susceptible to health problems.

Another researcher, Alan Zelicoff of Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, presented a study suggesting that a terrorist threat could be posed by an aerosol version of the virus that is more potent than naturally occurring strains.

His conclusions were based on recent reports about an accidental release of a weapon version of the smallpox virus in 1971 by Soviet scientists. The accident may have been responsible for a smallpox outbreak that is believed to have started when a boat passed by an island where testing of aerosol smallpox was taking place. Zelicoff said evidence suggests that an infected Soviet biologist on the boat spread the disease in a nearby city, where three people died.

Henderson, however, said there is not enough evidence to support what he termed Zelicoff’s “alarmist” conclusions.

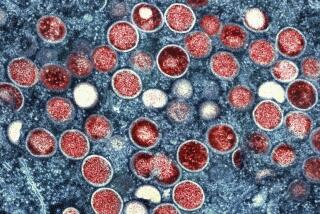

The smallpox virus typically spreads via infected saliva and face-to-face contact within about 6 feet. Early symptoms include fever, headache and backache, beginning about one to two weeks after exposure. That is followed by a severe skin rash on the face, arms and legs, during which time the disease is most infectious.

The last case of smallpox in the U.S. was in 1947. After Sept. 11, government officials began to fear that terrorists might get their hands on the virus and release it into the population.

In November, Thompson contracted with a British biotechnology firm to produce enough vaccine to inoculate every American by the end of this year.