In France, Police Morale Sinks Amid Sea Change

- Share via

ARGENTEUIL, France — These days, France is a tough place to be a cop.

About 10 miles from L’Etoile (The Star), the Parisian plaza where the Arc de Triomphe crowns a magnificent cityscape, three police officers venture warily into a high-rise housing project known as La Dalle--the Slab.

The 25 towers on a concrete esplanade here in Argenteuil, a working-class suburb of 140,000, are part of a gloomy wall of 1970s-era projects around Paris that are outposts of gangs and drugs. Leaving their cars out of range of balconies and rooftops from which youths bombard police with rocks and bricks, the officers descend into a grotto of abandoned garages. Their flashlights illuminate a subterranean cemetery of torched vehicles.

The officers plod through garbage and puddles and talk shop: There were three arson attacks on police substations last year. Threatening graffiti announce officers’ home addresses to the world. A suspect told a plainclothesman that he knew where the officer’s wife worked and that she would pay for his arrest. Mobs surround squad cars in melees that echo of May 1999, when two weeks of riots shook the Slab.

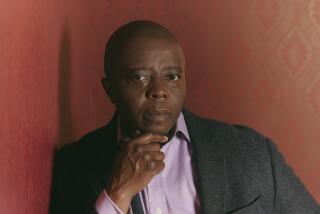

“For these kids, the only authorities are their parents and their big brothers,’ said Maj. Jacques Richard, a spry and bespectacled 27-year veteran. “They don’t want to listen to any other authority, not a policeman, not a teacher. The police are not respected. That’s why we’ve had a lot of injured cops.”

It is a time of discontent for French police. Crime was up 7.6% in 2001, continuing a trend marked by what police union officials say was a fourfold increase in physical and verbal assaults on officers in the last five years. Last year, more than 600 officers were attacked while on duty.

Ambitious attempts to reform hidebound laws and policing strategies have left officers feeling vulnerable and convinced that criminals are getting away with murder. Politicians seem out of touch with the street, officers say. Though crime is the top issue in a nascent presidential campaign, the Paris City Council in December named Mumia Abu-Jamal, a convicted U.S. cop-killer and a death penalty cause celebre, as an honorary citizen of Paris--a distinction last bestowed on Picasso.

Resentment in the ranks boiled over in November. National police officers held demonstrations across the country. Then came the turn of the gendarmerie, the force that patrols rural areas. The size of the protests by the disciplined gendarmes, who belong to the military and are barred from demonstrating, was startling. The gendarmes ended up in a tense but nonviolent face-off with riot police near the Arc de Triomphe.

Many demonstrators wore jackets adorned with targets and the slogan “We are not rabbits,” a sardonic reference to the killings of officers, which eventually numbered eight for the year, and the idea that cops have become easy prey.

2 Officers Slain

The most outrageous case was the ambush slaying in October of two officers responding to a home invasion. Suspect Jean-Claude Bonnal, an ex-convict accused of killing four civilians two weeks earlier in a holdup, had been released on bail the previous December--even though he was awaiting trial for a department store robbery that left nine wounded. Adding insult to injury, when a police union leader criticized the release and called Bonnal “dangerous,” the suspect sued him for defamation.

“This case was aberrant, and it’s what really set off the protests,” said Jean-Paul Nury, a leader of Synergie Officiers, a police union. “What we are saying is: Stop. Fear has crossed the street. Instead of the crooks being scared, the cops are scared.”

The most worrisome trends are a spreading drug-and-thug culture, especially among young men of North African descent, and the increased presence of assault rifles and other heavy weapons smuggled from the Balkans.

Recent cases display a high-caliber gangsterism that seems out of place in genteel Western Europe. Drug traffickers stormed a police station in Les Sables d’Olonne, on the Atlantic Coast, on March 2 and held a female gendarme hostage in a failed attempt to recover more than 700 pounds of cocaine. And 13 gunmen using explosives stole more than 1 million euros from an armored car depot in Paris two days later, injuring a policeman in a shootout.

In addition, the specter of Islamic terrorism hovers over high-crime neighborhoods with large Muslim populations. Extremists in mosques and prisons have recruited thousands of undercover warriors who have been trained by Al Qaeda and other networks, according to anti-terrorism officials.

However, the Sept. 11 attacks do not appear to have sparked street tension the way the Palestinian uprising has in the past. And violence transcends ethnicity and income. Rage against police flares in rural towns as well as cities, during routine traffic stops as well as felony interrogations.

“We have 55-year-olds who insult us and assault us,” said Emmanuel Roux, a 34-year-old commander in Argenteuil. “It’s as if nobody wanted to respect social rules. In all areas of social behavior, the respect for rules is disintegrating bit by bit, like old cement.”

Nonetheless, France remains less violent than the United States. In 2000, this nation of 60 million recorded 1,051 homicides compared with 1,000 in Los Angeles County. Rising crime in France results partly, according to experts, from increased reporting by victims and from a surge in street rip-offs of cellular phones--a frightening but usually not fatal experience.

So why the malaise among flics, as French police are called?

In a nation where conservative and revolutionary currents long have coexisted uneasily and people generally resist change, the police are caught in a cross-fire generated by recent and profound reforms in law enforcement.

In 1997, the center-left government unveiled a neighborhood policing program similar to those in the U.S. and elsewhere, promising to send police into communities and work closely with mayors and the poor alike to solve problems on the street.

In essence, says Dominique Monjardet, a sociologist at the National Center for Scientific Research, France has tried to tackle in four years the reforms that have taken decades to carry out in the U.S.

Moreover, the mission is harder in France. Since 1941, the police have been a paramilitary national force with a more aloof relationship to municipalities and citizens than in Anglo-Saxon countries. Monjardet said French police have always performed best in two areas: “public order,” which refers to controlling street protests and political unrest; and detective work against organized crime and terrorism.

In contrast, basic patrol and crime prevention have been neglected, he said. The officers abruptly ordered to walk beats and win hearts and minds in long-neglected housing projects--many full of youths seething with hatred of authority--tend to be rookies from small towns who find Paris menacing, alien and harsh. They are strangers on strange turf.

“It’s a good reform, but they are trying to do it too fast,” Monjardet said. “For the police officers, the message is that you have been doing a bad job. . . . They have been destabilized by rapid change. They went out into the neighborhoods, and they were received with rocks.”

The new show of force also has collided with a flourishing drug trade, with predictable results. Arrests and shootings in “sensitive zones”--the elegant sociological label for bad neighborhoods--often ignite mini-uprisings.

“There were neighborhoods where the police did not spend enough time,” said the cerebral Roux, who accompanies his espresso with Italian cookies and presided over a 4% decrease in crime in Argenteuil last year. “Money from drugs, vice and robberies is present, and the criminals don’t want the police there. So there was no violence. On the surface, everything seemed fine. When you have this kind of [unofficial] peace, the return of [official] order can cause trouble.”

Whether commanders or rookies, police say they are buffeted by contradictory social demands as well. French citizens generally want and expect government to play a central role in everyday life. People call the police for every imaginable problem, Roux said.

Yet the media and the political left are often critical of the police. Police union leader Nury calls it a “do-gooding soixante-huitard” mentality, a reference to leftists who came of age during the protests of 1968. Members of that generation are in power, he said, and expressed their ideology with a “presumption of innocence” law that has brought bitter debate since taking effect last year.

The law was designed to strengthen individual rights against an inquisitorial justice culture that had created one of Europe’s largest populations of suspects jailed while awaiting trial or indictment. The reform guarantees immediate access to a lawyer and other Miranda-type safeguards.

Effect on System Decried

Nonetheless, critics say the architects did not anticipate the disruptive effect on a creaky justice system. Detectives have less time to do the same amount of work needed to justify holding a suspect. Procedural breakdowns sometimes cause the release of dangerous offenders who in the past would have remained in jail, critics say.

Police also see aspects of the reform as insulting. They are required to summon doctors to ensure that suspects were not abused. And the government came up with sophisticated Web-cams to record questioning of juveniles while officers struggle with outmoded computers and rattletrap cars.

“The police have the impression that the other links in the justice chain are weak,” Roux said. “There’s a dire lack of resources, the stations are shabby, the weapons are outmoded. And if that’s not enough, instead of helping the police, money and energy are spent to aid bandits. That was very badly received.”

Mindful of presidential elections in April, the government has pledged to review the new law and to improve funding and salaries for officers. On the street, though, police insist that they are concerned less about money than about the onslaught of disrespect and aggression.

“The police are supposed to be the final bulwark of the democracy,” said Richard, a 53-year-old grandfather who worries about the future facing his son, also a policeman. “What does this attitude, this increase in violence, say about the democracy?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.