At Pig Farm, Vancouver Police Reap Grisly Clues

- Share via

VANCOUVER, Canada — She was one of the 50 “missing women,” as they are generically called here, a recent entry on the police’s numbingly long list of prostitutes who disappeared from the city’s seedy east side and are now feared to have been the victims of what could be one of North America’s worst serial killings.

But Sereena Abotsway is no longer counted among the missing.

Early this month, in the bright vaulted chambers of Vancouver’s Cathedral of Our Lady of the Rosary, she became the first of the 50 to be ceremonially put to rest. Slain sometime late last year at age 29 and declared dead last month, Abotsway was eulogized in a memorial Mass by a priest who knew her as a child and wistfully remembered her off-key hymn singing. Her half brother Jay Draayers chokingly recalled a protective but playful older sister with “roaring laughter and warm smiles.”

A prayer card distributed at the service bore a photo of this earlier, innocent Abotsway, taken long before she became a prostitute and drug addict, before her skull was fractured and her face disfigured in an assault that apparently occurred on what social workers here euphemistically term a “bad date.”

The text, a poignant remembrance of all the missing women from the east side, was written by Abotsway herself. She had joined the marches of feminists and downtown activists who had been demanding for a decade that city and federal police mount a joint investigation into the disappearances.

“When you all went missing each and every year we all fought so hard to find you,” Abotsway wrote. “You all were part of God’s plan. He probably took most of you home. But he left us with a very empty spot.”

There was no burial service for Abotsway, though. The family has nothing to bury.

In February, six months after she vanished from the gritty streets, police discovered what they told relatives were identifiable fragments of her body on the grounds of a Vancouver-area hog farm. Police also found the remains of another missing downtown prostitute, Mona Wilson. The farm’s 52-year-old co-owner, Robert William Pickton, was charged in their murders.

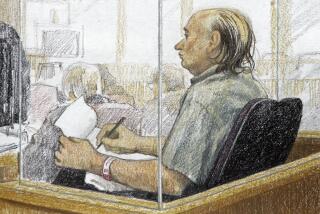

Pickton remained silent as the first-degree homicide charges were read to him in a two-minute court appearance Feb. 22 shortly after his arrest. He is scheduled to return to court next Tuesday to begin pretrial proceedings that experts say could take years, including a possible change of venue request from the defense. Pickton has not yet entered a plea, but his lawyers said he denies any role in the women’s deaths.

Authorities here are legally constrained from saying whether Pickton is believed linked to any of the other 48 cases.

Former Vancouver city detectives who were assigned to the cases and later left the force said they reported three years ago that they believed most of the disappearances were the work of a single killer or several operating together. Pickton was identified as a possible suspect in 1999, they said, but there was no systematic surveillance of him or his property until last year.

The Pickton farm in Port Coquitlam is now the focus of one of the most intense criminal investigations in Canadian history, with earthmovers scouring the 10-acre property for buried evidence and a team of Royal Canadian Mounted Police experts examining unearthed clues at an on-site forensics lab. More than 80 local and federal police and technicians are assigned to the investigation, police said.

Search of Farm Expected to Take Many Months

“The detailed, inch-by-inch search of the farm property will continue for many months to come,” Catherine Galliford, a spokeswoman for the joint city-federal police investigation, said after Pickton’s arrest. “We believe we now have answers regarding the disappearance of two missing women. But this is a case involving 50 missing women. There are a lot of questions still unanswered. We will not rest until those answers are found.”

On March 10, relatives of missing women were shown photographs of shoes, shirts, jackets, jewelry and other items that they assumed were recovered from the site, though police would not confirm that. Nor would police tell reporters whether the families recognized anything.

But Abotsway’s family said evidence they had been presented earlier, including DNA samples, showed that she and Wilson were victims of “very gruesome” killings. “There is definite DNA evidence that Sereena and Mona are no more,” said Bert Draayers, Abotsway’s foster father.

Prostitutes began disappearing from Vancouver’s east side in the mid-1980s, with cases climbing to three or four a year through the 1990s--a disturbing and statistically anomalous pattern that investigators then feared might suggest one or several serial killers. But it was not until 1999 that police publicized their first list of the missing women, circulating a poster featuring 31 faces--some from family snapshots, most from police mug shots--and an advertised $100,000 reward for information leading to arrests in what were presumed to be their murders.

Two of the 31 were soon found alive; two others had died natural deaths. But there was little progress on the other 27 cases. A police task force dwindled from nine investigators to two, and the reward offer was quietly shelved.

But the disappearances continued. In February 2001, community pressure and persistent media inquiries brought the federal resources of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police into the case. In December, 18 more names were added; in January, police listed five more.

Abotsway, unlike most women on the list, came from a tightknit family--a foster family, but one to which she remained close--with resources and social standing.

Otherwise, she fit the tragic profile well. Like most of the others, she was laconically described in police missing-person posters as a “known drug user and sex trade worker in the downtown east side area.” A decaying port district of flophouses and crack houses, Vancouver’s east side has long been the lowest-income census zone in Canada and has perhaps the country’s most visible concentration of hard-drug usage.

And like at least 21 of the 50 missing women, Abotsway was an American Indian, one of the “urban aboriginals,” in Canadian parlance, who have long been among the poorest of the poor here. They make up barely 3% of greater Vancouver’s population but account for more than half of its downtown street prostitutes. Many share Abotsway’s history of early-childhood abuse and subsequent foster care, a pattern disproportionately common among Canada’s native peoples.

Most of these women already had two strikes against them, as prostitutes and hard-drug users. Their ethnicity may have contributed further to the seeming official indifference to their fate, said Ernie Crey, a local American Indian rights advocate.

“From the beginning, the police all but acknowledged this, saying things like, ‘These people are different from us,’ ” said Crey. “There is a well-documented history of Native Canadians being mistreated by law enforcement, and so many of these women were of aboriginal ancestry. Might these attitudes have played a role in how their cases were handled? I think so.”

Crey believes the investigation is now quite rigorous. He is not a detached observer: His sister, Dawn Crey, is among the missing. Like Abotsway, she had suffered abuse in childhood and spent time in foster care, then went on to a life of prostitution and frequent drug use. In November 2000, at the age of 43 and after nearly a decade on the east side, Crey vanished. Her disappearance was reported by the methadone clinic she had begun to visit and by the welfare agency whose checks she no longer cashed.

Ernie Crey doesn’t know if his sister ever visited the Pickton farm, but other missing downtown prostitutes did, their friends say. When Heather Chinnock was last seen, she was talking about visiting the Pickton place, according to Garry Bigg, Chinnock’s fiance and a friend of others on the missing list.

Surrounded by encroaching suburbia an hour’s drive east of downtown Vancouver, the Pickton farm is a defiant remnant of a rougher, more rural British Columbia, replete with wrecked cars and shanty-like outbuildings. The chain-link gate is covered with warnings that may have once looked cartoonish but now seem menacing: “No Visitors, Agents, Peddlers or Salespeople--Admittance by Appointment Only!! (No Exceptions)” and “This property protected by: Pit Bull With AIDS.”

Outside the gate, makeshift shrines of flowers and candles and scrawled notes commemorate women thought by friends and family to have died inside: “To Kathy Gonzalez--’Forever Young, Forever Missed’ ” and “To Diane Melnick--I’m so sorry. Ingrid.”

The Pickton property is encircled with yellow police tape.

Imagining ‘Most Grisly Scenes Imaginable’

Speculation centering on the slaughterhouse and feeding troughs at the hog farm have compounded the horror for friends and relatives of the missing. “The police tell us almost nothing, and we are left to imagine the most grisly scenes imaginable,” said Suzanne Jay, a director of a Vancouver rape counseling center.

Jay says prostitutes are vulnerable to violence from many sources. The center’s extensive records of assaults against women--information that is routinely turned over to police but rarely prompts arrests, she says--show that many men here have committed violent attacks against prostitutes, runaways and other vulnerable women.

Karen Duddy, the executive director of Women’s Information Safe House, or WISH, a social service center for downtown streetwalkers, said Pickton and his farm were never mentioned in her agency’s internal “bad-date sheet” of confidential complaints about customers. However, the prostitutes did voice worries about frequent violent mistreatment by foreign sailors who brought them on board ships in the harbor. Police are belatedly but seriously questioning prostitutes about these and other leads, she said.

In 50 earlier killings of streetwalkers here--known to be homicides because corpses were recovered--police investigations led to the convictions of 17 individuals for “highly violent and sadistic” killings with knives or fists, said John Lowman, a criminology professor at Simon Fraser University. Most remain unsolved, however.

Lowman is calling for an inquiry into the city police department’s handling of the missing women’s case, which he contends was plagued by failures to reinvestigate convicted killers of prostitutes and to cross-check information with other law enforcement agencies.

However, Lowman said the bigger issue was the unwillingness of police and civic authorities to devote sufficient resources to the first wave of disappearances, which coincided with a city crackdown on street prostitution and failed to rouse mainstream concern.

Like some other close followers of the case, Lowman said he had initial doubts about the serial-killing hypothesis in part because it might discourage separate and thorough investigation of each case.

But now, after observing the intensive investigation at the hog farm, Lowman is changing his mind.

“The important thing is that this doesn’t stop here,” Lowman said. “We are a society with multiple personality disorder on this issue, and we have to deal with it.”

Uncovering evidence on the farm, if it is there, will prove difficult. Much of the property was used until recently as a commercial landfill site; it is covered with layers of trucked-in soil and refuse dozens of feet deep. Exacerbating the problem, much of the Pickton land is newly built over with tract homes, a real estate project that coincided with most of the disappearances.

Recently sold houses now overlook the overturned muck of the crime scene.

“They didn’t know anything about it when they bought their houses; then, hey, holy smokes, it’s right under their noses,” said Donald Stewart, a patrolman standing guard at the police-taped boundary between the hog farm and the Pickton family’s year-old “Heritage Meadows” housing development.

Before police began searching the farm last month, the biggest obstacle to the investigation was the lack of any forensic evidence--any proof, say some in the police department’s defense, that there were any homicides at all.

There was, however, one survivor of what police said was a near-homicide at the farm five years ago. Wendy Eistetter, also an east side prostitute, was stabbed repeatedly by Pickton at the farm in 1997 in what she said was a murder attempt foiled only by her furious resistance. Pickton was charged with attempted murder and “unlawful confinement.” Eistetter was hospitalized with scores of serious knife wounds; but so was Pickton, who claimed self-defense. When Eistetter failed to show up for pretrial hearings, the prosecution was suspended.

Evidence collected at the time may be introduced at the Abotsway and Wilson trials, prosecutors said as they won a court order earlier this month to have the 1997 records sealed from public use until then. Eistetter could be a key witness in the Abotsway and Wilson cases, prosecutors said.

In the five years since Eistetter’s stabbing, the number of reported disappearances of downtown prostitutes nearly doubled, note Crey and other relatives of the missing women.

“There are so many people with families out there like mine who are just beside ourselves,” Crey said. “However unpleasant the truth may be, we want to find out what happened.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.