A Hot Rodder’s Wild Ride

- Share via

Give up the dream. Collect $90,000.

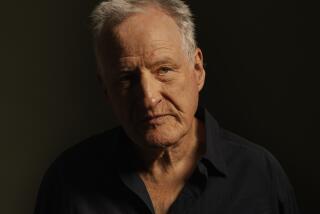

That was the option facing Long Beach writer and car enthusiast Mark Christensen several years into his decade-long pursuit to build, from scratch, the coolest car ever made.

Christensen had teamed in 1990 with Nick Pugh, “the best car designer of his generation,” and a succession of expert fabricators to create the 600-horsepower, natural gas-powered Xeno III. It was to be the ultimate hot rod that he’d failed to create as a teenager tinkering in his dad’s garage in an upper-middle-class suburb of Portland, Ore., in the 1960s.

Then things got complicated. And expensive. Pugh, whose influence can be seen in the bladelike diagonal lines of Ford’s “New Edge” designs such as the Focus, which break from the popular rounded look, and the Toyota Celica sport coupe, is a perfectionist. He wanted every nut and strut of the Xeno III finished like jewelry. Christensen approved. “In our butt-first-into-the-future, retro-obsessed age,” he says, “Nick Pugh is trying to create something really new.”

This was important to Christensen, 53, who says he grew up with the promise of a future in which people would drive rockets, live in circular glass houses and “be smoking pot on Mars by now.” He laments that future’s failure to arrive.

But the downside of Pugh’s unwillingness to compromise was that costs rose exponentially. Christensen, who has written about the car in his recently published “Build the Perfect Beast: The Quest to Design the Coolest Car Ever Made” (Thomas Dunne), says the project began when a physician friend offered to back it with $100,000-- a sum that, he realized later, might “buy the front bumper” for one of the exotic designs that Pugh, only 21 at the outset, envisioned.

In the end, the Xeno III cost about $600,000 to build, Christensen says, even though key parts--including the 502-cubic-inch big-block Chevy “Rat” engine--were donated.

“Building the Perfect Beast” consists of two interlocking stories. One, a black comedy, is about the scramble for money, the wooing of individual and corporate sponsors, the trying out and discarding of ideas--including a plan to have the car run on hydrogen “cracked” from ordinary tap water--and the clash of outsized egos.

The second story, more poignant, is about Christensen’s life. The son of a distinguished Portland eye surgeon, athlete and businessman who “had the best cars of his time,” Christensen was, like his hot-rodding friends, part of “a West Coast generation who grew up under an incredible lack of oppression,” he says, quoting fellow writer Charlie Haas.

“We thought we could do anything,” he explains. “Nobody ever said no to us--until we were arrested, or killed.”

Eventually, the Xeno III project--similar in complexity to constructing “a 15-foot-long Swiss watch”--cost Christensen his Portland house, his beloved old Porsche and, because of the delays, his original book contract. His publisher sued to recover the $50,000 advance.

At the low point, Christensen says, one of the natural gas companies that initially looked promising as a partner turned off the gas in the home his family was renting in Long Beach’s Belmont Shore district.

That’s when temptation beckoned. Out of kindness, one of his wealthier partners offered him $90,000 for his shares in the project.

If he took it, he could pay his bills. And he could claim that he had made progress on his journey from “spoiled son” to “responsible father”--his book’s second subject. Christensen and his wife, interior decorator Deborah Wenner, have two children, Katie, 21, and Matt, 14.

But he wouldn’t be proving himself “grown up enough to finish what I’d started.” And that, he thought, wouldn’t have pleased his late dad.

“If I’d taken it,” Christensen says, “I’d be a lot less happy than I am.”

His wife, at crunch time, supported him. And then funds poured in unexpectedly because one of his partners, businessman John Case, developed patents on an unrelated project, the storage of natural gas in a vehicle’s chassis, giving a van a potential 1,000-mile range.

Soon, Pugh, a former wunderkind at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, began to make big money selling ideas to movie studios. Meanwhile, Christensen, who began his writing career as a freelance journalist and now has novels and works of nonfiction to his credit, got a contract to write a book on the scientific quest for “secular immortality”--humankind’s efforts to live ever longer.

The car was finished last winter and is on display at So-Cal Speed Shop in Pomona, where it was built, a shrine to the hot rodder’s art where one can also see gleaming show cars and a racer made from a plane’s belly tank that hit 136 mph on a dry lake bed in 1948.

The Xeno III “has no skin,” Christensen says, at least, not in the traditional sense of a car’s outer covering. It has parts piercing through its outer layer and some portions of the covering are made of glass. “And, with its big, high-pressure fuel tanks and trapezoids of tubing, [it] looks like a cross between a bomb-laden, streamlined jungle gym and a chunk of the Mir space station,” he adds. In short, like no other car on Earth.

It’s for sale too, he says, for $1 million.

How fast is the Xeno III? Fast enough to take off and fly, Christensen figures. Fast enough, at any rate, to meet the project’s original specifications: a) Step on the gas. b) Hit the horizon.

Yet Christensen hasn’t driven it faster than 60 mph. At 6-foot-3, he can hardly fit in it after crawling into the cockpit--the Xeno III has no doors.

But he’s happy, he says, and so is Pugh. They’re still friends. “After the project was finished,” Christensen recalls, “we went out with a bunch of people and had about a million drinks and I was delighted, after all we went through.”

And yes, he says, he’d do it again.